Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| Reader Enquiries | |

| One Short Year Ago | |

|

Ship of the Month No. 60 MONARCH | |

| Additional Marine News | |

| Table of Illustrations |

The months of November and December are traditionally busy ones on the Great Lakes as vessel operators try to squeeze in as many trips for their ships as possible before the onset of winter conditions that close the rivers and canals and send the lakers to secure berths in port for the winter months. The steel mills need large supplies of ore to build up their stockpiles to last through the winter and the grain elevators must be filled to keep the flour mills and malt houses busy until spring. This late-season rush of vessel traffic was even more pronounced in the early years of the century than it is now due to the smaller size of the vessels then in use and the fact that year-round navigation was then nothing but a distant dream.

But these same two months are well known to the men who sail the lakes for the dirty weather that they are likely to throw up in the teeth of those ships running late to get in those last few trips. Blustering, chilling winds can whip the lakes into a frenzy and visibility is frequently reduced by snow squalls and by the mist that often develops over the cold waters. With batteries of modern electronic aids to navigation, the carriers of today can usually cope with such conditions without much difficulty, but the same could hardly be said for the steamers that plied the lakes around the turn of the century.

Indeed, the forbidding weather conditions of the late autumn were to be the undoing of many of the wooden and early steel steamers, not the least of which was the Northern Navigation Company Limited passenger and package freight steamer MONARCH. She met her end exactly seventy years ago this December in the cold waters of Lake Superior and this would seem to be an appropriate time to recount the details of her loss for those who may not be familiar with the story.

Back in 1865, James H. Beatty and Henry Beatty decided to form a partnership for the purpose of operating vessels on the upper lakes under the Canadian flag. They began to run steamers between Sarnia and the Lakehead and in 1870 they established what was known as the Lake Superior Line. The service grew into a thriving concern and in 1882 the Beattys incorporated as the North West Transportation Company of Sarnia, although the operation was familiarly known as "The Beatty Line".

The Beattys realized that in order to remain competitive they would have to make sure they were operating with the best of equipment and so in 1882 they contracted with the firm of Dyble and Parry for the construction of a 252-foot, wooden-hulled, passenger and package freight propellor [sic]. She was built over the winter of 1882-1883 at a spot near where the Imperial Oil docks are now located on the Sarnia waterfront. When she entered service she was generally considered to be just about the finest thing then afloat on the Canadian side of the lakes and her owners chose for her a name they thought appropriate for her position. She was christened UNITED EMPIRE, but the men around the lakes knew her simply as "Old Betsy".

UNITED EMPIRE was a truly beautiful ship, with a graceful, sweeping sheer to her decks, and a hull that was strengthened by arch trusses which rose to just below the level of the boat deck. She carried a single, tall mast forward and a fairly short but substantial funnel well aft. The funnel was surmounted by a rather unusual double cowl. Right forward on the boat deck was a very large and imposing square pilothouse, a perfect example of Victorian architecture with its sectioned windows and fancy work around the open bridge.

UNITED EMPIRE was an instant success and made quite a name for herself amongst the travelling public. Seven years later, the Beattys were in need of another vessel for their fleet and, having had so much success with "Old Betsy", they returned to Dyble and Parry with a contract for a similar boat. The new steamer was built in 1890, again on the shore of the St. Clair River at Sarnia. Another wooden-hulled passenger and package freight propellor, she measured 245.0 feet in length, 35.0 feet in the beam and 15.0 feet in depth. She was built with the usual 'tween decks and her tonnage was registered as 2017 Gross and 1371 Net. Her hull, built of the finest white oak obtainable, was strengthened with arch braces and gave the appearance of massive solidity.

The new steamer was christened MONARCH, a name fitting to

her position as the Beatty flagship. She was placed on the Sarnia - Lakehead run with UNITED

EMPIRE and the two ships provided a regular and dependable service for many years, formidable

competition for anyone else who might have thought of operating on the same route. MONARCH,

although a few feet shorter than her older running-mate, was very similar in appearance to

UNITED EMPIRE. Her pilothouse was somewhat less ornate, her arches were not quite

so high (they rose only barely above the promenade deck rail), and her funnel, although topped

by the same double cowl, was a bit taller and thinner, but apart from these minor differences,

the two were virtual sisterships.

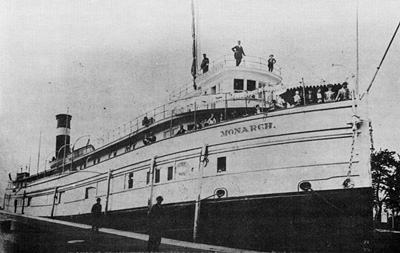

MONARCH is seen in the Soo Canal in this early photo. It can be dated as prior to 1899 as she still carries the insignia of the North West Transportation Company.

The two great steamers ran together on the route from Sarnia to Fort William and Duluth and during their tenure in the service they saw the Beatty operation grow from a small line to the largest firm operating in the passenger and package freight trade on the Canadian upper lakes. In early 1899, the Beattys merged their North West Transportation Company with what was commonly known as the White Line, the Great Northern Transit Company of Collingwood, a firm operating steamers on Georgian Bay and the North Channel. The resulting organization was known as the Northern Navigation Company of Ontario Limited and later in 1899 this enlarged concern was itself merged with the North Shore Navigation Company (familiarly known as the Black Line which had operated in opposition to the Great Northern Transit Company). This last merger resulted in the formation of the Northern Navigation Company Limited, a concern that for many years would dominate Canadian upper lakes passenger and freight services.

For several years, the Beattys continued to operate the new company and all the vessels of the Northern Navigation fleet were given the original Beatty Line funnel design, red with a white band and black top. These colours, of course, are still used by Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. of which Northern Navigation eventually became a part. That event, however, came somewhat later than the period with which we are concerned. Of more importance, at least as far as MONARCH was concerned, was the passing of control over Northern Navigation from the Beattys to H. C. Hammond of Toronto in 1904.

By this time, MONARCH was no longer the pride of the fleet, having been surpassed in size and luxury of fittings by the 321-foot steel steamer HURONIC which had been built at Collingwood for the fleet in 1902. MONARCH was, however, still a valuable unit and one whose services the company sorely needed to cope with increasing business. They were not to have her for long.

On the afternoon of Thursday, December 6th, 1906, MONARCH was lying at the freight sheds at Port Arthur, loading bagged flour which she was scheduled to deliver to Sarnia. It was to be her last trip of the season, for the wooden steamers were usually put into winter quarters before ice started to form on the lakes. Lake Superior was waiting for her with a nasty wind blowing out of the northeast and bringing with it a fall of fine snow and a layer of mist lying over the water. Loading operations were completed at about 6:00 p.m. and shortly thereafter MONARCH departed her berth en route to Sarnia. In the icy cold darkness, Capt. "Teddy" Robertson and his men on the bridge duly sighted the Welcome Isle light and also Thunder Cape as MONARCH steamed along towards Passage Island.

At about 10:00 p.m., the purser, Rig Beaumont, went down to the engineroom to chat with the chief engineer, Samuel Beatty. The purser commented on the fact that MONARCH seemed to be making very good time and wondered how this could be since she was loaded more deeply than usual and was heading into the freshening wind. He also mentioned that the ship was then abreast of Passage Island light, a statement with which the engineer took exception, for MONARCH was not due off Passage Island for another twenty minutes. As the two men continued their discussion and moved to a deadlight to take a look out into the evening darkness, MONARCH ran straight into the perpendicular rock wall of Blake Point on the northeastern side of Isle Royale.

The steamer hit the shore with such a wallop that Beaumont and Beatty were both knocked off their feet. By the time they had picked themselves up off the deck, they found that the ship was making water fast, the water pouring back into the engineroom like a millrace. The two men made their way forward to the passenger gangway on the main deck and there they tried to make a sounding through the port using a heaving line with a weight on the end of it. When they found that they could get no bottom even with ninety feet of line, they realized that they had best try to get ashore as soon as it was possible for MONARCH was almost certain to slip back off her rocky perch.

All hands made their way up to the boat deck and efforts were made to get the lifeboats away, but in the very cold and wet weather the falls had frozen up and when they did manage to chop them free, they could not keep the boats from falling into the lake. The deck crew remained above trying to find some way of getting ashore while the engineer and his oilers went back aft to tend the machinery. Despite the inrushing water, Beatty managed to keep the engine working ahead slow in the hope that this would keep MONARCH from dropping off the rocks on which she had impaled herself. One of the oilers, a fellow named Gillroy, remained in the stokehold shovelling coal until the rising water drove him from his post.

But before the steam failed and the lights were extinguished, Sam Beatty managed to crawl all the way forward over the bagged flour to see if by any chance a ladder would reach the shore from the anchor shutter in the starboard bow. Finding the distance to be too great to get ashore that way, the engineer returned aft to find that the water had risen so high in the engineroom that the cranks were actually throwing water. The stern of the ship had dipped so far down that the water began coming in aft at deck level and it soon drowned the dynamo, extinguishing the lights. Knowing that they were losing steam with no hope of keeping the engine turning, Beatty and his oiler gave up their stations and headed for drier ground. By this time the stern had settled so low that the only way they could make their way through the main cabin was by pulling themselves up hand over hand on the stateroom doorknobs, dodging the various furnishings which were tumbling down to the after end of the cabin.

By this time, the rest of the crew had assembled on the bow where they stood in the 20-below-zero temperature (and that's fahrenheit, not celsius) trying to figure out how to get somebody ashore with a line. One of the men volunteered to go over the rail on the end of a rope and he took with him the hooked ladder which was normally used for painting the stack. The men up on deck began to swing the rope back and forth, the man dangling at the end and reaching out on each swing in an effort to hook something on shore with the ladder. Eventually they got him swinging so far out that he was able to hook onto a rock and he soon managed to clamber up his ladder and reach solid ground, still holding onto the rope.

But the poor old MONARCH just couldn't stand any longer the weight of all that water dragging her down by the stern. She waited just long enough for the man to get ashore with his rope (but not long enough for him to secure it to anything) and then slipped back fifteen or twenty feet. At that point, the strain proved to be just too much for the hull and she broke apart forward of the funnel. The stern section dropped off and immediately sank in deep water, taking with it the entire cabin aft of the pilothouse and texas cabin.

It was indeed fortunate that a man had already been put ashore, for if he had not managed to land before MONARCH slipped back, it would have been unlikely that any of the crew could have survived the accident. As it was, the man ashore could do little but watch the rope pay out through his hands until it stopped just short of the point where it would have pulled him back off the rocks into the icy water. Very fortunately, the men left on the wreck were able to locate another rope and with this made fast to the end of the other line, they were able to give the man ashore enough slack so that he could secure the rope to a tree.

One by one the men left their precarious positions on the steeply sloping and icy deck and made the journey hand over hand along the rope across the fifty-foot gap between the ship and the shore. Even Miss MacCormack, the cabin maid, got safely ashore this way, although she did have to be rescued half-way across when her skirts became tangled on a hook that was attached to the line. Even so, it had been quite a struggle to get her to attempt the crossing and the crewmen were heartily glad that the ship was not carrying any ladies or children as passengers at the time of the accident.

The engineer meanwhile heard cries for help coming from the water below and, with the aid of a rope which had been on the forward capstan, he slipped over the side and landed in a lifeboat which had been jammed between the hull and the shore by floating cabin wreckage. There were two men in the boat and one, the watchman Jacques, was in the water hanging onto the gunwale. Before he could be pulled into the boat, he succumbed to the numbing coldness of the lake and let go his grip. His was the only life lost in the stranding. The men ashore dropped a line over the rocks and Beatty and the other two men in the boat were pulled up the precipice to safety.

At long last, everyone made shore safely, with the exception of the man who had drowned and the master of the vessel. Capt Robertson could not be persuaded to leave MONARCH and he spent the night in his cabin which had remained intact. He was to regret not having gone ashore.

The people who found themselves on the rocky shore of Isle Royale were safe from the icy water of the lake but they knew that unless they sought shelter higher up in the bush they could not survive the night. They managed to set fire to a birch tree and by its light they were able to gather up enough wood to build a fire around whose warmth they huddled through the night.

Friday morning dawned bitterly cold but clear, the storm having blown itself out during the night. Those ashore realized that they would have to get the captain off the wreck if he were not to freeze to death and they managed to get him to go over the side on a rope and lower himself to the wreckage in the water which had frozen solid during the night. They then pulled him up the rocks to safety. But Capt Robertson had suffered badly from frostbite in his unheated cabin during the night and in due course this would mean the loss of several toes. The crew built a small shelter for him and into it they also herded the purser, the steward and the cabin maid, the intrepid Miss MacCormack. Some of the bagged flour had floated clear of the wreck and this was rescued so that the wet dough could be cooked over the fire to provide sustenance.

After they had eaten, some of the men hiked across Blake Point and built a bonfire across from Passage Island lighthouse, hoping to attract the attention of a passing steamer with its smoke. They kept the fire going all day Friday and Saturday, but to no avail. There was still a layer of mist hanging over the water and this probably obscured their smoke from the view of passing vessels.

About noon on Saturday, four of the men of the party were sent on a search mission to Tobin Bay, a small community located across the island and off to the south of where MONARCH grounded. The chief engineer had remembered having seen houses there and the hope was that food and shelter might be available in the summer community, or even better, that someone might still be living on the bay. The search party was warned that even if they did locate food or shelter, they were not to return until daylight on Sunday. The reason for this was that the survivors had heard many wolves howling in the woods at night and it was not considered safe to be wandering about during darkness, especially when there was such a great risk of the men losing their way in unfamiliar territory.

By late Saturday afternoon, it had become evident that no passing ship had seen the survivors' bonfire and it was decided that an attempt should be made to attract the attention of the Passage Island lightkeeper. The men climbed up on a high rocky promontory on the starboard side of the remains of MONARCH from which they could see the lighthouse over the wreck. There they built a large fire just about that time of the afternoon when the light-keeper got his light going. The weather having cleared up considerably by this time, the lightkeeper saw the fire and indicated with his light and foghorn that he had seen the signal.

Sunday morning being clear and very calm, the keeper came over to the wreck in his small boat and he took Rig Beaumont, the purser, back with him to the lighthouse, the idea being that together they could hail a passing steamer and relay news of the accident and the whereabouts of the wreck. The first vessel to pass downbound on Sunday afternoon was the Mathews package freighter EDMONTON and they were able to stop her as she passed. Beaumont was taken out to her and when he had explained their predicament to the ship's master, EDMONTON was turned around and proceeded back to Fort William. On their arrival back at the Lakehead, the purser got in touch with the office of the Northern Navigation Company. MONARCH's owners lost no time in getting action underway and they arranged for the steam tugs JAMES WHALEN and LAURA GRACE to set out for the wreck first thing on Monday morning.

The tugs arrived off Isle Royale at about 10:00 a.m. but by

this time the wind had freshened out of the northeast and the tugs could not make a landing on

the exposed shore near the wreck. Accordingly, they circled around the point towards Tobin Bay

and there pushed as far as they could go into the ice which had formed along the shoreline. The

party of survivors set out from their encampment near the wreck, thinking that they would meet

up either with the tugmen or with the search party that had been sent to Tobin Bay the day

before. On the way, they located a rowboat which had been pulled up on shore and which was

found to be loaded with foodstuffs, a rifle, a hand-operated foghorn, and other assorted

goodies which would have been of assistance to the crew. They pressed on and soon met some of

the tugmen who had set out in search of them. They then learned that their search party was

already safely aboard the tugs.

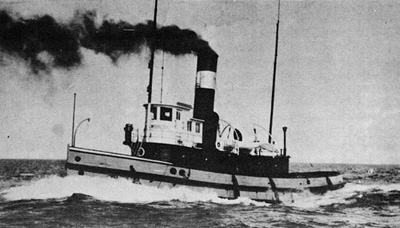

This is how JAMES WHALEN looked when she rescued MONARCH's crew from Isle Royale in December 1906. The tug was built the year before by Bertram's at Toronto.

Once the survivors were all on board the tugs, they learned that the row-boat which they had found had been left for them by the search party which had reached the houses at Tobin Bay without difficulty. They had found all the buildings to have been vacated for the winter, but as they were all fully stocked and there was no caretaker about the premises, they had made themselves quite at home and had rather enjoyed their chance to get out of the elements and into warm cabins with soft beds.

With all of the MONARCH's people aboard, JAMES WHALEN and LAURA GRACE set out for Fort William. On the way, engineer Beatty found out that one of the men on the tugs was Hugh Myler, a gentleman who was actually chief engineer on SARONIC, the former UNITED EMPIRE (sistership of MONARCH), which at the time of the accident had happened to be in port at the Lakehead. He had come along because he was concerned for the safety of his brother David who was second engineer in MONARCH.

The tugs arrived in the Lakehead at about 7:00 p.m. Monday evening and landed the survivors almost exactly four days to the hour from the time when MONARCH had set out from the same port on her last voyage. With the exception of Capt. Robertson whose frostbitten condition demanded that he be sent back to Sarnia by train, all the MONARCH survivors were placed aboard the Northern Navigation flagship HURONIC for delivery to Sarnia.

The remains of MONARCH rested on the shore of Isle Royale for two years. During 1908 the Reid Wrecking Company sent a crew to the Blake Point area and they located the stern section of the steamer. Her engines and other machinery were salvaged and the rest of the wreckage was left to moulder away where it lay.

MONARCH came very close to completing her sixteenth year in service. Her crew, we are quite sure, would have wished for her last trip to be somewhat less eventful, but a certain degree of consolation could be found in the fact that only one life had been lost in an accident that could, but for a bit of good luck, have been much more costly in terms of human life.

UNITED EMPIRE, by then renamed SARONIC, carried on for nine years after the loss of her sister, although not all of these years saw her running on her original route. She herself was damaged by fire at Sarnia on December 15, 1915, this same fire having destroyed the Northern Navigation steamer MAJESTIC. SARONIC was cut down first to a steam barge and then, after a 1916 stranding on Cockburn Island, to a towbarge. She lasted until 1924 when she was abandoned in the Detroit River near Amherstburg due to her age and condition.

(Ed. Note: The details of the actual stranding of MONARCH and of the adventures of the survivors on Isle Royale have been adapted from an account by the engineer, Samuel Beatty, as told to C.H.J. Snider and reproduced as "Schooner Days - DXXIV", appearing in The Evening Telegram, Toronto, on Saturday, December 6, 1941, thirty-five years to the day after the wreck. We thought it only fitting that the story appear in these pages now that another thirty-five years have passed. Our apologies to the late Mr. Snider for the liberties we have taken with his article to make Beatty's account more suitable for inclusion in our own story of the life and death of MONARCH.)

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.