Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Ship of the Month No. 146 Cayuga | |

| Barney Adam | |

| Marine News | |

| Segwun in 1986 | |

| Table of Illustrations |

When our very close friend and founding T.M.H.S. member, Alan Howard, passed away during January 1986, many kind words were said about his numerous contributions to the preservation of the history, marine and otherwise, of the Toronto area. Alan, of course, was the first curator of the Marine Museum of Upper Canada, and served in that capacity from 1961 until 1981. However, Alan Howard did something even more important in terms of an attempt to preserve "live" marine history; he was given an opportunity that most of us would never have and which most would never grasp even if they could. Alan, a longtime resident of Toronto's Centre Island, had been interested in the passenger ships of the area since his youth, and in the mid-1950s he was given the chance to resurrect one of them and to return her to service after her previous owners had retired her.

The steamer was the famous Niagara River excursion vessel CAYUGA, and Alan and his supporters were able to operate her for four additional summer seasons, until events totally beyond the control of Alan's firm combined to make further service impossible. For many years, we have promised to feature CAYUGA in these pages and fortunately we now have sufficient material available, primarily as a result of its preservation by Alan Howard, that we can now present our feature, albeit somewhat belatedly. We hope that our members will enjoy it, and that it may serve as a memorial to our late friend and member.

Much has been said in these pages, over the years, of the history of the Niagara Navigation Company Ltd., Toronto, and we do not propose to repeat the details here. Suffice it to say that, in 1877, the Hon. Frank Smith and Barlow Cumberland acquired the upper lakes passenger steamer CHICORA, a former Confederate blockade runner (see Ship of the Month No. 47, March 1975). They rebuilt her as a day boat, brought her to Lake Ontario, and in May of 1878 they placed her on the route between Toronto and the Niagara River, having sold her to the Niagara Navigation Company, which Smith and Cumberland had formed for the purpose. The first issue of the new firm's stock was completely subscribed by the Smith and Cumberland interests, and the Hon. Frank Smith was named president of the company, while Barlow Cumberland became vice-president, a position that he would occupy until his death in 1913. The first directors were Col. Fred W. Cumberland, John Foy and R. H. McBride. Barlow Cumberland was also named manager, while Foy became the firm's secretary.

By the early years of the twentieth century, the company was firmly established as one of the most successful passenger services on Lake Ontario. Niagara Navigation was running the big sidewheelers CHIPPEWA, CORONA and CHICORA on the route, thus permitting six sailings in each direction per day. Service was provided to Niagara-on-the-Lake and Queenston on the Canadian side of the river, and to Lewiston on the U.S. side. However, CHICORA, as popular as she always was, was growing older and required increasing maintenance. Fortunately, her unusual oscillating machinery was still efficient, if not easy to operate, and it kept her in service, but it had been decided that a new and much larger, propeller-driven steamer should be constructed.

Mr. B. W. Folger (of the family which for many years had operated passenger steamers on the St. Lawrence River), who had been named to the position of general manager of Niagara Navigation in 1902, was sent to Great Britain to make enquiries concerning the construction of a new steamer, but it was eventually decided once again to engage the services of Arendt Angstrom, the noted marine architect, to prepare the designs for the new ship. Angstrom probably ranked second only to Frank E. Kirby in respect of the beauty of the vessels that he created, and the Niagara Navigation Company certainly held him in high repute as a result of his previous work for the fleet.

The steamer that he designed was the vessel that came to be known as CAYUGA, and the contract for her construction was let late in 1905 to Angstrom's firm, the Canadian Shipbuilding Company Ltd., which built her at Toronto as its Hull 100. According to her Certificate of British Registry (issued at Toronto on 2nd January, 1907, Official Number 122219), the steamer was 305.OO feet in length, with a beam (of hull only) of 36.67 feet, and a depth of hold from the tonnage deck to ceiling amidships of 14.25 feet. The length of her engineroom was 118.00 feet. Tonnage was 2195.78 Gross and 1167.53 Net. Other sources stated that her beam across the guards (in other words, the breadth of her main deck) was 51 feet, 8 inches. Her overall length was 317 feet, 6 inches.

She was powered by two quadruple expansion steam engines, which were built by the shipyard, and which had cylinders of 17 1/2, 25, 36 and 52 inches, and stroke of 30 inches. The engines produced 4,300 Indicated Horsepower, or 328.75 Nominal Horsepower on steam at 210 pounds pressure. Steam was supplied by seven coal-fired Scotch marine boilers, which measured 11 feet by 12 feet, and these also were built for CAYUGA by the shipyard.

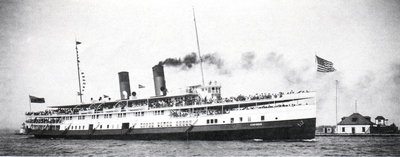

This interesting Pringle & Booth Ltd. photo of CAYUGA outbound at Toronto's Eastern Gap, probably was taken in her second year of service.

The April 1906 issue of "The Railway and Marine World" reported on the advent of CAYUGA. "The launch of the new steamer for the Niagara Navigation Co. took place from the builder's yard in Toronto, March 3rd. Notwithstanding the heavy rain and the strong south-east wind that was blowing during the morning, and which was particularly heavy at the time of the launch, there was a very large number of persons present. The christening ceremony was performed by Miss Mary Osier, daughter of E. B. Osier, M.P., president of the company, and the name CAYUGA was given to the new steamer as she left the ways.

"The vessel is planned on the lines of the day service observation type of steamer, having four principal decks, namely, main deck, promenade deck, upper promenade deck, and lower or orlop deck below the main deck. The hull is of steel, with bilge keels to reduce rolling to a minimum... Internally, the hull is divided into eight watertight compartments by seven bulkheads, thus rendering her practically unsinkable. She will be driven by twin screws, power being supplied by two sets of vertical inverted, direct-acting quadruple expansion engines, balanced on the most modern principle... (Each of the seven boilers will be) fitted with two corrugated furnaces, and a system of heated draught.

"Two smoke stacks will be provided, similar to the other steamers of the line. The steamer is to have a guaranteed speed of 22 1/2 miles an hour. The engines are designed to develop 4,300 h.p., which is about 30 % greater than that developed by the MONTREAL, at present the most powerful Canadian steamer, and is only exceeded by a very few passenger steamers on the U.S. side of the Great Lakes.

"The interior arrangements of the steamer are primarily arranged to provide the greatest conveniences for the passengers. There will be three gangways on each side, the forward ones for passengers and express, the middle ones for passengers' baggage, and the aft ones for passengers only. This latter will lead directly into the entrance hall on the main deck, at the forward end of which will be found the purser's office, a parcel checking room, and other offices with which passengers have to come in contact. At the aft end will be the ladies' retiring room, which will be specially fitted for the comfort and convenience of ladies, and will include a number of new features.

"At the forward end, a staircase 7 ft. wide will connect the entrance hall with the promenade deck above. The dining room will be forward on the main deck, and will be fitted with large observation windows on each side, so that an uninterrupted view may be had. It will have a seating capacity for 150. The main deck will be of steel covered with wood, and interlocked rubber tiling will be used as a flooring in several parts of the vessel devoted to passenger accommodation.

"On the promenade deck, the principal feature will be the general saloon, which will extend the full width of the steamer. It will be a particularly handsome apartment, and the sides, instead of being straight, will consist of a series of bow windows, so that views may be had ahead and astern as well as straight out. At each bay, seats will be provided so that small parties may keep together. Two of the bays (one on each side) will be finished as private parlours, which will be available for letting to parties who desire to be alone.

An early Niagara Navigation advertisement (and postcard) shows five views of CAYUGA's interior.

"The upper promenade deck, which will be reached by a stairway from the general saloon, as well as by stairways from outside on the promenade deck, will extend over the whole vessel, instead of ending just forward of the wheelhouse as in most vessels of this type. The rail will be inside the lifeboats, and the entire width of the deck will be available for passengers. The captain's quarters, the wheelhouse and the pilot's room will be on this deck. A light shade deck amidships will give shelter over this deck. The space over the engineroom, instead of being closed in with steel plates, will be surrounded with a framework in which plate glass sides will be fixed so as to enable passengers to have a view of the machinery. On the lower or orlop deck, will be found the quarters for the crew, kitchens, smoking room, engines and boilers, etc.

"The decorations will be particularly striking. The entrance hall will have a heavy beam ceiling: the main stairway will be in cathedral oak; the dining room in mahogany, and other portions of the passenger accommodation in weathered and quartered oak. The designs show some very fine effects, and will present a rich and artistic appearance. The furnishings of the various rooms will be in harmony with the general decorative design and colour scheme.

"Following the launch, the Canadian Shipbuilding Company entertained a large party, including representatives of the municipal and financial interests of the city, and of the transportation interests in Canada and the United States associated with the Niagara Navigation Co., at lunch at the King Edward Hotel. The toast list was a short one, F. Nicholls, president of the shipbuilding company, opening the proceedings; the Mayor of Toronto (Emerson Coats-worth) proposing prosperity to the Niagara Navigation Co., and E. B. Osier replying; D. R. Wilkie proposing the shipbuilding company, A. Angstrom, its general manager, replying; the sponsor of the steamer proposed by Barlow Cumberland, vice-president of the Niagara Navigation Company; our Canadian allies, proposed by H. J. Pearce, president of the International Traction Co., Buffalo; and manager of the N.N. Co., which was acknowledged by B. W. Folger.

"The CAYUGA will be completed for the current season's traffic, it being expected that she will be ready to take up the run on June 15, when in conjunction with the CHIPPEWA and CORONA, the full service of six trips a day will be given. The CHICORA will be held as a spare steamer, ready for any emergencies. "

In Chapter XVII of his book, A Century of Sail and Steam on the Niagara River, Barlow Cumberland commented upon the naming of the steamer. "We were again faced with the necessity of a choice of a new name. Requests were made for suggestions, and 'Book Tickets' offered as a prize to those who might send in the name which might be accepted. Two hundred and thirty-three names beginning with 'C and ending with 'A' were contributed to us by letters and through the public press. Out of these names, the name CAYUGA was selected in recognition of the Indian tribes on the south shore of Lake Ontario, the district of the inner American lakes, in the state of New York, one of which bears the name of Lake Cayuga.

"It is also the name of an old and flourishing town in Ontario, near the shores of Lake Erie, adjacent to the land reserved for the Mohawks under Brant, and still occupied by their descendants. A very interesting annal was at that time exhumed, being the record kept by the first Postmaster of this town of Cayuga, of the spellings of the name of his post office as actually written upon letters received there by him during a period of some twenty-five years. The list is curious. (Indeed, for Mr. Isaac Fry's record contains 112 ways of spelling the town's name, some of them of the most peculiar nature - Ed.) It seems strange that there could have been such diversity of spelling, but it is to be remembered that in the "thirties" there were not many schools, and by applying a phonetic pronunciation to the names in this list, and particularly by giving a 'K' sound to the 'C' and splitting the word into six syllables and pronouncing each by itself, some appreciation may be acquired of a similarity in sound, although the spelling is so exceedingly varied. The adherents of spelling reform will perhaps be heartened by the result of everyone spelling as they please."

We will not comment further on Mr. Cumberland's obviously strong views on the subject of spelling reform. Suffice it to say that the company rejected such inventive spellings of the name as "Kukey", "Cugga", "Kiucky", "Cyug" and "Keugeageh", and opted for the more traditional spelling that we have all come to know!

The completion of CAYUGA was, however, a far more lengthy job than the writer of "The Railway and Marine World" article had imagined. In fact, the ship was not ready for her builder's trials until mid-August of 1906, and although she operated on a trial basis on the Niagara route in the autumn of 1906, she did not take her place in the company's schedule until 1907. Mr. Cumberland described the fleet's requirements for the ship: "After the completion of "the steamer, the speed trials, which were of a most interesting and important character, were engaged in. The contract was that the steamer, under the usual conditions for regular service, should make the run between Toronto and Charlotte, and return, a distance of ninety-four miles each way, at an average speed of 21 1/2 miles per hour. A further condition was to make a thirty-mile run, being the distance between Toronto and Niagara, at a maintained speed of 22 1/2 miles per hour. Both conditions were exceeded, greatly to the credit of the designer and of the contractors."

The April 1907 issue of "The Railway and Marine World" provided this description of "The Steamer CAYUGA's Trial Trip: As the Niagara Navigation Co.'s new steamboat CAYUGA will be in service next summer, the following report by Capt. C. Moller, of her trip from Toronto to Charlotte, N.Y., and return, on Wednesday, August 15. 1906, will be of interest: 9 a.m., took in moorings and left dock. 9:30 a.m., passed through Western Gap, course S.W. 1/4 W. by comp. towards Port Credit. 10:10 a.m., turned ship, steering E. by S. by comp. Port Credit bore by comp. W. by N. 10:32 1/2 a.m., Gibraltar Pt. bore by comp. N. by E. dist. 5.6 miles. Log 9'. wind easterly, moderate breeze. 0:25 p.m. (12:25 p.m.), Olcott Lt. bore by comp. S . by W. dist 8 miles. Log 38.5. 1:01 1/2 p.m., 30 Mile Pt. bore by comp. S. by W. dist. 7 miles. Log 48. 2:53 p.m., Braddock Pt. bore by comp. S. by W. dist. 6 miles. Log 77.5. Average speed 19.3 miles for trip across. Wind easterly, light, sea smooth. 6:14 p.m., Braddock Pt. bore by comp. S. by W. dist. 6 miles. Log 86. 8:03 p.m., 30 Mile Pt. Lt. bore by comp. S. by W. dist. 7 miles. Log 117. 10:12 p.m., Gibraltar Pt. Lt. bore by comp. N. by E. dist. 6 miles. Log 154 1/4. Turned ship round and steered for Eastern Gap. 11:30 p.m., moored alongside dock, Toronto. Average speed 21.2 miles for return trip.

On the return journey to Toronto, after leaving 30 Mile Pt. at 8:03 p.m., the boat arrived at Gibraltar Pt., a distance of 47 miles, at 10:12 p.m., being an average speed for this part of the run of 22.4 miles per hour."

The results of the trials of CAYUGA were obviously pleasing to her owners but the delay in getting the boat ready for service certainly was not. The February 1907 issue of "The Railway and Marine World" stated that "the report for the year ended Nov. 30, 1906, presented at the annual meeting (of the N.N.Co.) in Toronto, Jan. 8, stated that the failure of the builders to complete the new steamship CAYUGA in time for service during the season of 1906 was a disappointment. A reduction of the price was made on account of delay in delivery. The trial trips were most satisfactory, and the vessel will be ready for the season of 1907. The cost of CAYUGA (the construction account then showed $266,137.90 - Ed.) has been nearly covered by cash on hand and proceeds from the sale of stock, so that of the bonds authorized, it will probably suffice to sell only whatever may be required to take up the old bonds which matured Jan. 2, 1907." The same report went on to state that "the old board was re-elected with the exception of R. H. McBride, who was replaced by W. D. Matthews. The directors for the current year are: president, E.B. Osier; vice-president, Barlow Cumberland; other directors: Hon. J. J. Foy, J.Bruce Macdonald, C. Cockshutt, Col. J. S. Hendrie and W. D. Matthews."

CAYUGA began regular service on the Niagara Route on Monday, June 10, 1907, and her first commander was Commodore John McGiffin, the fleet's senior captain, who likewise had been on the bridge of CHIPPEWA when she made her inaugural run in the spring of 1894, and who had also served in CHICORA, CIBOLA and CORONA. The addition of the 2,500-passenger CAYUGA was a great benefit to the company, for it meant that it could much more easily carry the throngs of Torontonians who sought to escape the heat of the city streets during the summer months. A particular consideration was that a Saturday afternoon half-holiday had become commonplace amongst Toronto businesses (partly at the instigation of the N.N.Co.), and many workers thus freed from the confines of offices and factories flocked to the docks to catch the afternoon sailings for Niagara. The licensed capacity of CHICORA was only 875 in latter years, while CORONA was licensed for 1,450 and CHIPPEWA could carry 2,000. (We rather wonder how often this latter figure was enforced, for turn-of-the-century photos of CHIPPEWA show such massive crowds of people on her decks that it seems impossible that only 2,000 people were on board.)

CAYUGA proved to be a worthy fleetmate for CHIPPEWA and CORONA; CHICORA was then reassigned to other duties, although she would fill in on the Niagara route if required. CAYUGA was not only mechanically satisfactory, but she also proved to be immensely popular amongst the travelling public. True, the beautiful CORONA and the huge CHIPPEWA, with her familiar walking-beam, retained their places in the hearts of those who frequented the cross-lake steamers, but CAYUGA brought a breath of fresh air to the route.

In addition, CAYUGA was a very handsome ship. Her hull sported a most graceful sheer, which was complimented by the fine lines of her superstructure. Her two tall masts and the two well-proportioned funnels, widely spaced in tandem, were heavily raked and gave the ship an appearance of great speed. Her pilothouse, with its tall sectioned windows, its flying bridgewings, its open bridge on the monkey's island, and its beautiful wood and canvas nameboard across its lower front, was a typical Angstrom creation. Her hull was painted black and, during the N.N.Co. years, the black was carried up to the top of the main deck rail. The upper part of the main deck cabin, and all of the rest of the superstructure, was painted white. The stacks were crimson with black smokebands. During her first season of service, CAYUGA carried her name in large gold letters on the main deck rail amidships, but as far as we know, this was removed after the 1907 season. We rather wish that the gold letters had remained, for they fitted in well with the ship's graceful and yet rather stately appearance.

Fortunately, CAYUGA was to enjoy a long and extremely successful career, one that was notably free from major accident of any kind, apart from the usual altercations with wharves, particularly in the strong current of the Niagara River. In fact, CAYUGA was designed with twin screws not only to give her a good turn of speed, but also to facilitate the manoeuvring of the vessel. One of the most dangerous things that the ships had to do was to turn in the river between Lewiston and Queenston below the whirlpool, and although the river current would spin the ship quite nicely if she were properly positioned, a fair degree of manoeuvrability was required to take care of the turn if un-pected [sic] events developed, as well as to facilitate landings. In fact, the entire Niagara Navigation fleet achieved a most admirable safety record over the years, the only disaster to strike the company being the loss of its second boat, the 1887-built CIBOLA, by fire on the night of July 15, 1895, as she lay at the Lewiston dock. There were no passengers aboard and only one life was lost, that of the third engineer who was trapped below.

CAYUGA was of such a length that she was unable to fit into any drydock on Lake Ontario except that which was operated by the Dominion government at Kingston. All of the Niagara Navigation boats were forced to use this dock and thus the Kingston shipyard did a roaring business serving the needs of the fleet. CAYUGA made her first visit to the drydock there in the autumn of 1907, after the regular season had concluded, in order that longer propeller blades could be fitted, presumably in an effort to enhance her rate of speed.

In 1908, CAYUGA faced her first serious competition when the turbine steamer TURBINIA was taken off her usual Toronto - Hamilton route by the Turbine Steamship Company, and was placed briefly on the Niagara service. TURBINIA, as a one-ship operation, could in no way compete with the six daily sailings provided by the Niagara Navigation boats, and so she soon retired to her Hamilton route, which in 1909 would be merged into the expanded (under Eaton family management) operations of the Hamilton Steamboat Company.

Then, in 1911, the Niagara Navigation Company bought out the Hamilton Steamboat Company, and thus acquired TURBINIA, MACASSA and MODJESKA, which were left to do their own thing on the Hamilton service. This move made certain that there would be no serious challenge to the N.N.Co.'s supremacy on the Niagara run. The next year, 1912, saw Niagara Navigation itself acquired by the huge Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company Ltd., which had long enjoyed amicable arrangements with the N.N.Co. for the through-routing of passengers from the Buffalo and Niagara areas to the ports of the St. Lawrence River. The N.N.Co. was retained as a corporate entity within the R. & 0., and there was no apparent change in the operation of its vessels, except for the departure from the board of the former Niagara Navigation directors.

In 1913, however, the Richelieu and Ontario was the major firm involved in the incredible series of mergers that resulted in the formation of Canada Steamship Lines Ltd., Montreal, and it was thus that CAYUGA became part of the largest fleet ever to sail the lakes under the Canadian flag. The "Niagara Navigation Division" remained as an operating division under the C.S.L. flag, it sometimes being referred to as the "Niagara River Divison".[sic] It was not until April 25. 1916, that CAYUGA's registry certificate was endorsed to indicate that C.S.L. was the registered owner of all sixty-four shares in the vessel.

On August 19. 1910, at age 68, Commodore John McGiffin had passed away at Toronto. He had suffered from diabetes for some years, but had been on duty in CAYUGA until a few days before his death. A suitable period of mourning was observed for Capt. McGiffin, and to this day there exist several photos of the Niagara steamers flying their ensigns at half-staff in his honour. Capt. C. J. Smith was appointed master of CAYUGA and fleet commodore on June 24th, 1914. and he was to remain in her for twenty-one years.

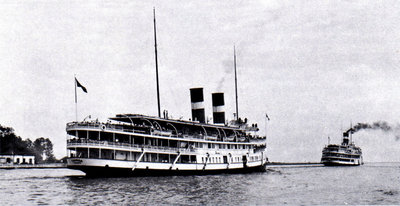

During her early years, CAYUGA, headed for the Eastern Gap, passes the small ferry ELSIE, which was bound for the City from Ward's Island.

Meanwhile, in 1915, there began a dispute between C.S.L. and the Department of Transport, Steamship Inspection Service, concerning the number of lifeboats carried by CAYUGA. Because she had but six lifeboats and five rafts (although she had seven sets of davits), her licensed passenger capacity had been reduced rather considerably from the original 2,500 figure. Her owners wanted her reinstated for a capacity of 2,150 passengers, and there followed much argument over the fitting of additional buoyant apparatus, including two Englehart collapsible boats. The company even went so far, over the years, to add extra davits and transfer boats from other steamers which laid up early for the winter, in order that CAYUGA would not have to operate on a grossly reduced ticket during the month of September, when large weekend crowds were often attracted to the lake. This dispute went on for well over ten years before it was finally resolved, and eventually CAYUGA sported ten boats, with an additional supply of floats, rafts, etc., available.

CAYUGA did not always confine herself to the Toronto - Niagara route, and occasionally she would be chartered for service elsewhere on Lake Ontario. It is reported that, on June 7, 1922, she was granted a special certificate for one day only to allow her to operate a special charter excursion from Charlotte to Cobourg and return. Such trips, while not exactly commonplace, were certainly not unusual for CAYUGA, and she made a number of them during her career. She always carried an Inland Passenger Class II certificate, and accordingly it was necessary for her owners to obtain a special permit if ever it was intended that she should stray off her normal Niagara route.

In November of 1924, the steamship inspectors found evidence of general corrosion and wasting in all seven of the boilers. A reinspection in January of 1925 indicated extensive leakage attended by serious wasting of the shells of all of the boilers at the under-part of the circumferential seams, and under all of the butt straps. It was ruled that very extensive repairs would be necessary, or else a reduction in working pressure must very shortly follow. In fact, during 1925, the working pressure of the boilers was reduced from 210 to 205 p.s.i. as a result of the reduced thickness of the shell plating. This was the beginning of a series of boiler problems that would dog the vessel for the next two decades, and even though the wastage and leakage problems encountered in 1925 were repaired, additional difficulties developed, and they grew ever more severe as the years passed.

Another problem encountered during 1925 was a government demand that C.S.L. fit deadlights on all of the hull portholes below the main deck if their lowest edge was less than 24 inches above the water line at load level. It seems that there had been occasions on which the portholes in the crew accommodations had been left open, due to poor ventilation on the orlop deck, and water had entered, either due to inclement weather on the lake or as a result of waves from passing vessels.

In May of 1928, CAYUGA was due to go on drydock, but no accommodation in the Kingston shipyard could be secured, due to a rush of repair work there, and an extension until autumn was granted. As it turned out, additional appeals were made by the owners due to a heavy movement of fruit from Niagara to the Toronto markets, and it was not until October 11, 1928, that she finally went on the Kingston dock. She remained there until October 16, with only minor work required, and then returned to Toronto for the winter. She was on the Kingston dock again October 8-26, 1929. for the fitting of a new starboard tailshaft and propeller. She received a new rudder whilst she was on the dock October 28-31, 1930. Her next drydocking, May 2-4, 1933, revealed that only minor work was necessary, but still, yet and again, the inspectors decried the worsening condition of her boilers, new faults being found on each inspection.

When CAYUGA was on the dock September 15-20, 1934, she underwent the renewal of various sections of her sheerstrakes. She was back in service in the spring of 1935 with Capt. H. W. Webster, a long-time C.S.L. master, appointed to her on May 9th. For the better part of the next two decades, Capt. Webster and Capt. J. D. Strachan took turns serving as master of CAYUGA.

CAYUGA was on the dock at Kingston May 1-3, 1939, for the examination of her port screw, which was causing trouble. It was found to be loose and so was drawn and refitted, with the shaft coupling bolts renewed. There must have been something more seriously wrong, however, for she was back on the dock, May 10-14, 1940, at which time an entire new port tailshaft was fitted, complete with a cast steel hub.

All passenger operations are likely to receive complaints from time to time, and while some are well founded, the majority are usually from persons suffering real or imagined slights which prompt them to view the entire operation with a jaundiced eye. One such complaint concerned the "terrible overcrowding" of CAYUGA (which by then was the only ship left on the Niagara line, CHIPPEWA and CORONA having fallen victim to increasing age and the effects of the Depression). The passenger was on the 2:38 p.m. Toronto sailing on Sunday, August 18, 1940, and a government investigation revealed that there were 1,957 passengers on the Toronto sailing and 2,128 on the return trip from Queenston. No official action was taken because the ship was licensed to carry 2,152 passengers and 73 crew, for a total of 2,225 souls.

In May of 1941, two additional metal lifeboats were transferred to CAYUGA from the idle C.S.L. night boat TORONTO. In October of that year, the steamship inspectors remarked that both furnaces in all seven of the boilers were deformed out of roundness, but she was passed for continued service on the basis that the deformities were not too severe but would be watched for a worsening of the condition. She was on the Kingston dock May 14-19, 1942, and both of her tailshafts were drawn, one new blade being fitted on the port screw.

During June of 1942, as a result of enquiries made in 1941, the steamboat inspectors ordered that additional seating was to be provided to help eliminate standing crowds, that extra deck patrols were to be instituted to keep passageways clear and to help control smoking in the main deck cabin, that the men's toilets on the main deck were to be relocated to space formerly occupied by officers' cabins near the engine casing so that passengers would have no reason to go on the cargo deck except whilst embarking or disembarking, and that passageways to the cargo deck were to be kept closed at all other times. As well, the stairway from the general saloon to the cargo deck was to be kept closed, except whilst in port. The stairways leading to the pilothouse and upper bridge were to be removed and the ladder to the pilothouse was to be extended to the passenger deck and a door cut in the aft end of the pilothouse so that the officers could go on the upper bridge without traversing the passenger deck. As well, runways were to be added to the dock at Niagara-on-the-Lake to help alleviate "bottleneck" conditions which often were experienced at the gangways. All of this work was soon put in hand by Canada Steamship Lines.

On July 8, 1942, the ship was cleared for one trip to Kingston drydock, without passengers, and although no reason was given, it is evident that she must have sustained damage of some sort. In August of the same year, several crew complaints were received as a result of the very poor ventilation in the orlop deck quarters, and inspection revealed that these complaints were justified. The company then installed a rudimentary air-conditioning system (fans) in the area, and the complaints were, apparently, satisfied. Her May 1944 drydocking at Kingston was deferred due to the dock being occupied, and she did not get docked until September. During November, all of the boiler furnaces were trammelled to determined their out-of-roundness, and the inspectors again shook their heads.

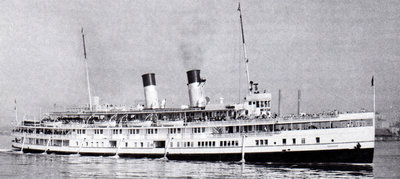

A typical scene has CAYUGA following KINGSTON out the Eastern Bap. Photo was taken in the late 1940s by Rowley Murphy, with Alan Howard by his side.

The 1945 season brought more complaints of overcrowding and fire hazard on board CAYUGA, but in all cases the inspectors found operations to be well within the requirements. The D.O.T., however, took a dim view of the worsening boiler problems, and it was ruled that either new boilers would have to be fitted or else the ship's working pressure would have to be greatly reduced, something that her owners did not relish in the slightest.

CAYUGA's certificate was withdrawn for a month in the spring of 1946 due to an insufficient number of certified lifeboatmen being carried aboard but she was permitted to operate until the situation was rectified. Also, in May of 1946, the inspection service decided that "the ship has been permitted to carry more passengers than can be justified by any existing regulation", and accordingly her summer season capacity was reduced to 1,850 passengers and 75 crew. The main problem noted by the inspectors was that the lifeboats were on the upper promenade deck, rather than atop the hurricane deck, and thus the crew would have to cross crowded passenger areas to reach the boats in an emergency, possibly resulting in a delay in effective action. A reduction in licensed capacity was thus considered desirable.

From September 30 until October 3. 1946, CAYUGA was on the drydock at Kingston. All her sea valves and cocks were removed and replaced by bronze fittings from an R.C.N. frigate, all tested to 100 p.s.i. When she was undocked, she went into winter quarters at Kingston, the first and only time in her life that she spent a winter away from Toronto. Her seven old boilers with their fourteen jacked-up furnaces were taken out, and in their place were fitted two new watertube boilers of the Yarrow type, which were built for the ship by John Inglis and Company, Toronto. Of "Landing Craft" design, boiler number 4878 (aft) and 4879 (forward) were given forced draft and were fitted to burn oil fuel. The main steam pipes were all replaced with six-inch diameter solid drawn pipe, tested to 800 p.s.i. Much new auxiliary equipment, such as pumps, was also installed, and accordingly, CAYUGA was again permitted a working pressure of 210 p.s.i. As a result of inclining tests performed in April of 1947. 75 long tons of permanent ballast was installed in the hull to make up for the weight lost when the old boilers were removed.

CAYUGA operated well with her new boilers, once more being able to attain good speed on her cross-lake runs. In April of 1948, she was given two new cast iron, six-inch diameter main throttle valves, which were manufactured by the James Morrison Brass Company, Toronto. CAYUGA was drydocked at Kingston August 13-20, 1948, following the breaking of the first length of her starboard intermediate shaft, with the resulting loss of the tailshaft and propeller. She was given the spare tailshaft and a length of intermediate shaft from the carferry ONTARIO NO. 1, with modifications performed to suit, and a spare screw was also fitted. CAYUGA was not long away from the shipyard, however, and was back on the dock September 21-25, 1948, for inspection to see if any damage had been suffered when she struck the bottom in the Eastern Gap. None was found.

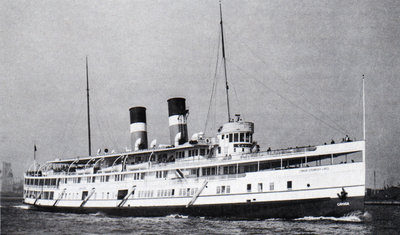

CAYUGA, in C.S.L. colours, is outbound at the Eastern Gap on September 17, 1949. Photo by J. H. Bascom.

From October 1st until the 26th, 1949, CAYUGA was again on the dock at Kingston to have two new solid manganese bronze screws fitted. Her shafts were drawn and it was found that both intermediate shafts had small fractures at the forward end in the key way. New intermediate shafts were fitted and the port tailshaft was also renewed.

The 1950 season was a difficult one for all Canadian passenger ships for, at a time when passenger revenues were declining as a result of road competition, the federal authorities instituted strict new fire safety regulations as a result of the burning of the C.S.L. steamer NORONIC at Toronto on September 17, 1949. One of the vessels that could not be altered to suit the new rules was C.S.L.'s KINGSTON, the beautiful sidewheeler which ran between Toronto and Prescott, and thus the company also dropped its connecting rapids services on the St. Lawrence River. One might have thought that CAYUGA, also running a connecting route, might also have fallen by the wayside, but the company recognized that she still had potential in her own right as an excursion boat, and a great deal of money was spent on her. Fire detectors, alarm sirens, and a public address system were fitted on all decks, and fire patrols every thirty minutes, twenty-four hours per day, were added. Fireproof bulkheads were installed, a sprinkler system was fitted, and steam smothering apparatus was placed in the boiler, lamp and paint rooms.

CAYUGA, resplendent with all these modern innovations, was allowed to operate with a limit of 1,850 passengers, as before. She was on the Kingston dock July 11-13, 1951, as a result of damage to her starboard propeller sustained when she struck a submerged object whilst leaving the wharf at Niagara-on-the-Lake on July 3rd. Her starboard shaft was realigned, and she was brought back to Kingston on September 19th for the fitting of the new propeller that had been ordered. Apart from the trip back to Toronto, however, C.S.L. got no use out of the new wheel, for CAYUGA went into winter quarters at Toronto and was not fitted out during the 1952 and 1953 seasons. Despite the extensive upgrading of the ship that had recently been done, the writing was on the wall for passenger operations everywhere.

There were, however, some folk who missed the cross-lake passenger boats (for even the Port Dalhousie route had now been abandoned) and felt that some sort of passenger service might still be viable. One of those who felt this way was Alan Howard, who set about raising interest in such a project. Some 1,300 small shareholders were lined up, and the Cayuga Steamship Company Limited was incorporated by letters patent dated 26th March, 1953. the firm opening offices at Toronto. Authorized capital was $500,000. The directors of the new company were D. Roland Michener, Q.C., president (in later years, he was to become Governor General of Canada); George Edgar Mallen, vice-president; William Miller Wismer, secretary; Arthur Charles John Franklin (Mayor of St. Catharines in 1953), treasurer, and Alan Howard, who took on the very important job of managing director.

A wholly-owned subsidiary of the new firm was the Cayuga Navigation Company Limited, on whose behalf the parent company purchased CAYUGA from C.S.L. The sale price was $100,000 and included in the deal were the docks at Niagara-on-the-Lake and Queenston, free of any encumbrance. The company was assured by the Department of Transport that CAYUGA was in compliance with all regulations, and work on readying the ship for service in the 1954 season was undertaken.

During the 1953-54 winter, while she was lying in lay-up along the west side of the Yonge Street passenger wharf at Toronto, CAYUGA was given new stack colours. The funnels were painted a deep crimson, with a very narrow white band, and a broad black smokeband. There exist very few views of the ship with her stacks painted in this manner, for the colours were soon changed. It is understood that the former owners objected on the basis of there being too much resemblance to their own colours, despite the fact that the chosen design bore more similarity, in fact, to the colours carried a half-century earlier by the racer TURBINIA.

On a hot summer morning in 1954, CAYUGA heads across Toronto Bay, outbound on her first trip of the day to Niagara. J. H. Bascom photo.

In any event, CAYUGA's stacks were repainted a buff colour, with a silver band and a black smokeband, in roughly the same proportions as had been the bands in her C.S.L. days, and the improvement was remarkable. Her cabins remained white, and the hull up to the main deck was black. (During the C.S.L. years, CAYUGA's hull had been first black, then white from the mid-1920s into the 1930s, and thereafter a very dark green.) Her new houseflag incorporated a blue 'C on a white square in the centre of a white cross, the upper left and lower right quadrants of the field being blue, and the other two quadrants red.

In view of the drydocking of the boat in the autumn of 1951, and her subsequent inactivity, the authorities agreed to defer the docking of CAYUGA until the spring of 1955. thus saving the fledgling company a great deal of initial expense. The inaugural trip of CAYUGA was a cruise of the Toronto waterfront for company shareholders and invited guests, sailing from Pier Nine, foot of Yonge Street, at 3:00 p.m. on Tuesday, June 8th, 1954. However, as successful as the first season might have been, her new owners might well have shied away from the entire project had they known what lay in store for them.

The schedule for the 1954 season ran through until September 12th. Daily, CAYUGA sailed from Toronto at 9:00 a.m. and from Queenston on the return trip at 11:50 a.m. (Sailing time Toronto to Niagara-on-the-Lake was two hours even, and the river trip to Queenston took 35 minutes.) Wednesday, Saturday, Sunday and Holidays, there was a 2:45 p.m. sailing from Toronto, the return trip from Queenston commencing at 6:30 p.m. On Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday, CAYUGA sailed from the city at 6:00 p.m., while the return trip departed Queenston at 8:50 p.m. On Saturday, Sunday and Holidays, there was a moonlight trip to Niagara-on-the-Lake only, leaving at 9:45 p.m. and arriving back in Toronto at 2:10 a.m. (Lewiston had ceased to be a stop for the Niagara boats back in the years of C.S.L. operation.) Fares were $1.80 one-way for adults and $3.25 return. Children under twelve passed for 85 cents one way and $1.50 return. For automobiles (limited capacity), a single passage cost $5. What a bargain by today's standards*.

The return of CAYUGA to the route was relatively successful, although her absence of two years meant that the people of Toronto had to be re-educated about the pleasures of lake travel, and it was becoming far too easy to take the highway to Niagara. She made it through the year under the guidance of Alan Howard from the office (and frequently on board to make sure that everything was done right), and of Capt. J. D. Strachan, master; F. Schutske, first mate; G. R. Profit, chief engineer, and D.W.D. Rose, second engineer. At the end of the season, however, the ship did herself an extensive injury when she hit quite forcibly the pilings at Queenston, reportedly fracturing or buckling twenty-nine sponson braces on the port side. The damaged braces were replaced or faired up during the winter lay-up, and there was also considerable renewal of the starboard fender strakes and many oak deck stanchions.

Things started to go sour for the new operation during the 1954-55 winter, when the D.O.T., having previously assured the company that CAYUGA complied with all regulations, decided that it really did not like the steam smothering system in the boiler room. It demanded controls to permit the stopping of the boiler fans and the closing of the dampers from outside the boiler room (not such a major job), the fitting of closeable plates over the spaces around the funnels where they passed up through the deck (an impossibility in the case of the forward stack), and the installation either of a foam system that could fill the boiler room to the top of the boilers very quickly, or else a carbon dioxide system that could produce 25 percent saturation.

The company argued itself blue over these desirable but hopelessly expensive alterations but, despite the sympathy of the local inspectors, its pleas fell on deaf ears in Ottawa. It finally was agreed that the opening at the forward stack could remain as long as the CO2 system would flood the boiler room to a 40 percent saturation. The rather disheartened directors of the firm took steps to begin the necessary work and set about finding additional financing for the company. A second brush with the unyielding Ottawa bureaucracy involved the conversion of the galley stove from coal to oil fuel, so as better to serve the needs of Canterbury Foods, which operated the food concessions on CAYUGA. Again, a myriad of regulations was invoked and the fuel tank that was installed was condemned and ordered replaced mid-way through the season as a result of a dispute over the thickness of the steel used. CAYUGA was on the Kingston drydock on May 2k, 1955, and all was found to be in order. A deferment of the pulling of her shafts was granted because shaft work had been done late in 1951 and the ship had operated only one three-month season in the interim. She entered service on June 11, with fares the same as the year before, and with only minor changes in the schedule. Friday was added to the weekend and holiday portion of the timetable, as that was a good night for the moonlight trade. Strachan and Profit remained master and chief, respectively, but V. W. Kake took over as first mate, and M. O'Neal as second engineer. Once again, however, the end of the season brought with it new problems. An inspection of the machinery on October 26, 1955, revealed that the first Intermediate Pressure crank pin was cracked, and the crankshaft would have to be replaced. The new section was manufactured and fitted early in 1956, and the work readily passed inspection.

CAYUGA began her third season of restored operation June 16, 1956, and, as difficult as it may seem to believe, fares remained exactly the same as the two previous years, except that a one-way ticket for an auto went up by $1.00 to $6.00. Messrs Strachan, Profit and O'Neal remained in the ship, while G. Stone became first mate. On June 13. 1956, just before her regular runs began, CAYUGA ran a special charter for the Cobourg Lions Club, departing Cobourg at 8:00 a.m. and sailing from Rochester on the return trip at 7:30 p.m. A special permit issued to the ship for that trip allowed her to carry 1,200 passengers and 75 crew.

The steamship inspectors had been watching CAYUGA carefully because of anxiety over the large number of passengers (1,850 on regular trips) allowed on board this ship with her wooden superstructure. As a result, CAYUGA often was visited by inspectors, who invariably would find deficiencies of one sort or another despite the best efforts of the company. On August 4, 1956, an inspector decided to ride the Saturday moonlight to Niagara-on-the-Lake, which did not get back to Toronto until almost three o'clock Sunday morning.

He once again found deficiencies and noted that, despite the best efforts of the officers (who had put in a long day), there was considerable "rowdyism" aboard, and several groups appeared to be well under "the influence". They must have brought their own supplies, because there was no bar on the boat. When CAYUGA was some three hundred feet off the end of Pier Nine at the end of the trip, a young couple (belonging to one of the groups) was apparently doing something atop one of the handrails, when the two fell overboard. Life-saving apparatus was thrown into the water but despite the efforts of the local Harbour Police and the ship's crew, the young man was drowned, although his female companion was rescued.

Needless to say, the incident again brought into question the nature of the operation. The company was doing the best it could on a restricted budget and it was finding great difficulty in securing competent crew members. To make it worse, the weather during the 1956 summer was, to say the least, hostile to the excursion trade, and by the end of the year, it was evident that the Cayuga Steamship Company's three years of operation had resulted in a deficit of $75,000 - not a small sum for a firm supported by small shareholders.

No decision about the 1957 season was made until just before CAYUGA was to begin operation, but the shareholders finally decreed that the company would persevere in its efforts to make the service pay. The ship was hurriedly drydocked at Kingston June 15-18, and she returned to Toronto on the 19th. That evening, she ran a special charter cruise, and she began her regular run on June 21st. On June 22, her second day of regular service, Capt. Strachan suffered a heart attack as CAYUGA was ending her afternoon trip. In the resulting confusion, the steamer swung wide of her berth, striking her starboard side heavily against Pier Ten on the east side of the Yonge Street slip. On June 23rd, inbound at Toronto in the afternoon at the close of the second trip under command of relieving master Capt. D. W. Livingstone, she made a heavy landing and damaged her port side. The vessel was out of service on June 26, 27, 28 and 29 for repairs to the damage caused in these two accidents .

On June 30, despite the blowing of danger signals by CAYUGA, she struck and overturned a small boat which interfered with her whilst she was turning in the current off the Queenston dock; the occupants of the boat were rescued by another yacht. Then, on July 5th, she somehow managed to get a wire wound on her port propeller. These incidents were all relatively minor, but they show what kind of a season CAYUGA had that year.

In an effort to increase revenues, the company jacked up its fares for the 1957 season, adult tickets rising to $2.20 one way and $3.90 return. Children travelled for $1.10 one way or $1.95 return. It cost $7.50 each way for a standard automobile or $5.00 for a small car. The ship's officers were: J. D. Strachan (June 20-22), D. W. Livingstone (June 23 - July 3), V.W. Kake (July 4 - August 6) and J. M. Andrews (August 6 - September 4), master; J.H. J. Frost, first mate; R. G. Johnston, second mate; W. E. Spry, third mate; G. R. Profit, chief engineer; M. D. O'Neal, second engineer; G. A. Freestone, third engineer, and R. Irvine, fourth engineer.

One of the problems encountered during the 1957 season was a new requirement that the ship be fitted with a self-contained diesel fire pump with sea suction. It was duly installed, and the inspectors then began to criticize the electrical system, noting many "faults" and changes that were considered to be necessary. As well, the inspectors were frequently on hand to observe the fire and boat drills, which usually were held whilst CAYUGA was bunkering at the Imperial Oil dock in the Toronto ship channel.

It soon became evident that 1957 would be the final season for CAYUGA, whether the travelling public knew it or not. The ship was still a class operation, with all navigation done from the open bridge rather than from the pilothouse, and with the ship usually blowing her deep steam whistle instead of the nasty typhon that had been added during the C.S.L. years. CAYUGA's last day of service was Labour Day, Monday, September 2nd, and she made her usual three trips, despite overcast weather with fog, and heavy rain setting in as she went out for her moonlight. CAYUGA arrived back at Pier Nine at 2:25 a.m. on Tuesday, September 3. 1957. and the crew spent the rest of the day preparing her for winter lay-up. The final entry in her log book, penned by first mate Frost, is dated September 4, 1957. and reads: "S/S heaved ahead along wharf and securely moored port side to in winter berth. All heavy work completed and crew discharged this p.m."

CAYUGA spent the winter and the early part of 1958 up at the head of the Yonge Street slip. The company had lost another $70,000 in 1957 and could not raise the funds to operate in 1958. It was hoped that if CAYUGA lay idle during 1958, the firm might be able to reorganize in time for the opening of the 1959 season, but this was a forlorn hope. It was also said that CAYUGA might be sold for use in the Montreal area after the opening of the Seaway, or even for use as a ferry in South America, but nothing came of these plans either. During the spring of 1958, the tugs SOGENADA and J. C. STEWART hauled CAYUGA away to a berth along the north harbour wall between the Bathurst Street and Spadina Avenue slips. There she lingered, growing ever more shabby, and sustaining damage each time the winds, to which she was greatly exposed, forced her against the wharf. Quite severe damage was occasioned in this manner to the main deck cabin aft on the port side.

During October 1960, two businessmen, Charles Santos and Joe McCarthy, were identified in the press as "new owners" of CAYUGA, and although first reports indicated that they would put her back in service, stories of a few days later spoke of her use as a restaurant. Needless to say, nothing at all came of the project. In the summer of 1961, CAYUGA was acquired by Greenspoon Bros. Ltd., a local demolition firm, and during the latter part of July, the dismantling of the ship began. By late autumn, only the hull was left, and it, too, was cut into sections and lifted out of the water during 1962.

Fortunately, due to the efforts of Alan Howard and the generosity of the demolition firm, the monkey's island from atop CAYUGA's pilothouse was saved, along with much of her navigation equipment. It was installed in the Marine Museum of Upper Canada, placed in front of a huge photograph of that familiar view looking aft from the open bridge, down the hurricane deck toward the twin funnels. The display remains a lasting reminder of the once-proud ship. As well, many Torontonians in whose hearts CAYUGA had occupied a special place, responded to Greenspoon's advertisements in the local press and bought mementoes of the vessel, thus preserving many more parts of the CAYUGA, both large and small.

It can be seen that CAYUGA's operators had many difficulties trying to keep the ship running. Surely, one might think, the excursion trade was enough to generate the necessary revenue, particularly with a big ship like CAYUGA. Unfortunately, such was not the case. Many factors combined to end CAYUGA's service, and the one that the Cayuga Steamship Company most blamed for its failure was its inability to obtain a liquor license for the ship. Occasionally a special charter party would be permitted to run a bar aboard, but the Liquor License Board of Ontario steadfastly refused to consider a regular bar aboard. The additional revenue which would have come from bar sales would almost by itself have wiped out the company's defecit.[sic]

The requirements of the Department of Transport also had much to do with the death of CAYUGA. In the 1950s, the preservation of operating steamboats was not the "in thing", and officialdom's foremost consideration was the preventing of loss of life by fire, especially so since C.S.L. had lost three of its lake and river passenger boats by fire in the space of only five years. Deviations from the rules simply were not possible, whereas today's even more stringent regulations may occasionally be relaxed somewhat in deserving situations. The overwhelming cost of upgrading a ship of CAYUGA's age could not be taken lightly, but even more frustrating was the fact that her last operators could never tell what new safety requirement would by lying in wait for them, and something new was almost always in the works.

The success of highway travel also was a major knife in the ribs of the lake steamers. With the improvements that had taken place in highway construction, people could drive to Niagara in much the same time it took CAYUGA to get there, and in addition they would have the car with them to go sightseeing whilst there. True, autos could be taken aboard CAYUGA, but in such limited numbers that a serious trade in carrying cars (and their drivers) across the lake could never be developed. A vessel of a different design might have been able to do it, but CAYUGA certainly could not.

By today's standards, the fares charged for passage in CAYUGA seem ridiculously low, but in the 1950s, they were not considered to be a bargain, and any increase in fares was met with a decrease in number of passengers carried. Thus, CAYUGA's owners could not generate sufficient funds to cover their expenses with the original fare structure, and the increased prices netted them even less. And expenses were ever on the increase, an example being that the D.O.T. demanded that "mature persons" instead of college students be hired (at greatly increased salaries) to attend to deck patrols on CAYUGA.

And we must not forget the bad weather of 1956 that put the icing on the cake. Excursionists stay away from boats in droves when the weather is bad, and CAYUGA was no exception. We remember seeing her with her decks almost bare just because the weather was a bit inclement, and money could not be made under those conditions, praticularly [sic] with intermittent competition from the Hamilton Harbour Commission's steamer LADY HAMILTON.

Yes, we mourn the loss of the faithful old CAYUGA, our friend of so many years, but we must ensure that those few historic vessels we still have remain with us. After being resurrected from apparently hopeless inactivity, ships such as SEGWUN and TRILLIUM are too valuable to lose, and the same will be true of G. A. BOECKLING as her restoration nears the operational stage. We must attempt to safeguard such treasures from the perils that may lie in wait for them, and ensure that they do not go the way of our old CAYUGA, despite the difficulties that may be encountered in keeping them in service.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.