Table of Contents

Three of the most famous ships ever to sail the Great Lakes were the Anchor Line "triplets" INDIA, CHINA and JAPAN, beautiful combination passenger and package freight steamers that served their original owners for more than three decades and enjoyed long lives in lake service. Little has been written about these steamers in the Canadian trades that they served after leaving the Anchor Line fleet, although we did feature CITY OF OTTAWA (formerly INDIA) as Ship of the Month No. 54 - February, 1976, issue. As the better part of another decade has now passed, it seems appropriate to present the story of another of the trio, and so we feature herewith the steamer JAPAN.

JAPAN (U.S.75323) was built at Buffalo in 1871 as Hull 9 of the King Iron Works, with Gibson and Craig serving as sub-contractors in her construction. Designed for both passenger and general cargo service, she had an iron hull up to the main deck, while her 'tween decks, topsides and cabins were built of wood. She was 210.0 feet in length, 32.6 feet in the beam, and 14.0 feet in depth, and these dimensions gave her tonnage of 1239.46 Gross and 932.02 Net. A propellor, she was originally powered by a simple one-cylinder, low-pressure engine, which had a cylinder 36 inches in diameter, and a 36-inch stroke. Steam was provided by one firebox boiler, which measured 12 feet by 16 feet. JAPAN'S machinery, which was built for her by H. G. Trout and Company, Buffalo, developed 51 Nominal Horsepower and 410 Indicated Horsepower.

JAPAN and her two sisterships were all completed during 1871, and they were then placed in service by E. T. Evans and his son, J. C. Evans, of Buffalo. In the 1860s, they had operated Evans' Buffalo, Milwaukee and Chicago Line, and also Evans' Atlantic, Duluth and Pacific Lake Company. Their operations had been absorbed into the Erie and Western Transportation Company, which became the lake steamship subsidiary of the Pennsylvania Railroad, and which came to be known as the Anchor Line.

With 114 years now having passed since the construction of the famous trio, it is not generally recognized today that, in fact, there were four steamers built for the Evans' in 1871 by the King Iron Works. The fourth was ALASKA, 212.6 x 32.0 x 13.9, 1288.06 Gross, 1147.92 Net, whose hull was almost exactly the same as INDIA, CHINA and JAPAN, but whose superstructure differed rather substantially in that ALASKA was completed as a package freighter, with no passenger accommodations. ALASKA, just like the passenger "triplets", was registered at Erie, Pennsylvania.

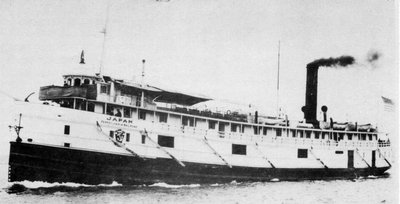

JAPAN was somewhat larger than most of the passenger steamers of her era and was thus rather impressive in appearance. Her hull was green up to the main deck and white above, with a narrow red stripe and a heavy wooden rub rail separating the two sections. The hull was given a pronounced and graceful sheer, and sideports were fitted on each side of the ship to facilitate the handling of package freight, most of which was either carried aboard or taken onto the ship in small, wheeled carts. Stocked anchors were carried on either side at the bow, the anchors being stowed on the main deck behind a normally-closed port. If one of the anchors had to be dropped, it was hoisted out and over the side by means of a small davit which was mounted on the promenade deck, just abaft the base of the steering pole.

Turn-of-the-Century photo by Young shows JAPAN upbound above the Soo Locks in the colours of the Anchor Line.

The vessel's name appeared in fancifully shaded letters on the wooden promenade deck rail forward, and also on an elaborately lettered nameboard which was hung on the side of the ship just ahead of the forward engineroom port. As well, the ornately lettered name and port of registry appeared on the vessel's rounded and rather bluff stern, just above the main deck fender strake.

On the promenade deck was carried JAPAN'S passenger cabin, a long, wooden structure which ran from well forward almost to the fantail. As was the case with most contemporary steamers, the cabin came to a point at its forward end and many of its curve-topped windows sported exterior louvred shutters that could be closed to keep the sun (and also inclement weather) from penetrating the interior and thus embarrassing the occupants. These privacy shutters, we believe, were painted green, to match the rest of the steamer's trim. The "boat deck forward originally came to a point, slightly overhanging the promenade deck cabin, but later the forward end of the boat deck was extended out into a balcony-like bridge with wings protruding out to the sides of the ship. Just abaft the bridge front was an ornate octagonal ("birdcage") pilothouse, which quite frequently was partially hidden by a high canvas weathercloth which was strung up on the bridge rail. Aft of the pilothouse was the texas cabin, which contained the quarters of the senior deck officers.

From just abaft the texas cabin, there extended down the boat deck a large clerestory, which gave light to the interior of the main cabin below. Passengers venturing onto the boat deck could stroll there, or could sit on large wooden benches. Part of that deck was covered by a large canvas awning to provide shelter from the heat of the summer sun. Four large lifeboats were carried on the upper deck, two on each side, although two additional boats were later added, to make a total of six - three per side.

JAPAN boasted a very tall and heavy fidded, gaff-rigged foremast, on which she originally carried auxiliary sail. This mast was heavily raked, as was a thin and rather short mainmast, which later was stepped forward of the funnel, and which appears unlikely to have served any particularly useful purpose. A very tall flagstaff rose from the fantail. The stack, which was tall, beautifully raked, and complimented on each side by a large ventilator cowl, was located well aft, and its top was decorated with a double-roll cowl. The stack was painted crimson, and did not have a smokeband.

JAPAN and her sisters did lack one of the features that was sported by many of their contemporaries. Wooden-hulled passenger boats of their era were generally the proud possessors of hog-chains, carried high over the boat deck on poles, or of arch trusses (or hog-braces), which were arched wooden beams on each side of the ship, all of this gear designed to give longitudinal strength to a large wooden hull. But, as INDIA, CHINA and JAPAN were built with iron hulls, they did not require these additional means of support, even though they otherwise did not look much different from other combination steamers of their period.

One remarkable feature of JAPAN and her sisterships was visible from a considerable distance and served as a method of ship identification. Instead of the usual ornamental ball or eagle, each of the "triplets" carried atop her pilothouse a lifesize wooden likeness of a native of the country for which she was named. These statues were the treasured trademarks of the three Anchor Line sisters, and they were retained until the vessels received new pilothouses in later years under the Canadian flag.

The ornately outfitted "palace steamers" of the 1850s had long since been retired and dismantled, and the travelling public had been obliged to content itself with the rather spartan accommodations provided on lake passenger ships of the 1860s. INDIA, CHINA and JAPAN, however, were veritable palaces in comparison with their contemporaries, and they would attract a remarkable patronage throughout their years of passenger service. Their staterooms opened off a long open passageway, into which the "grand" stairway up from the main deck opened, and in which the dining tables were set at mealtimes (no separate dining saloon being provided or even considered in those days). At the foot of the elegant companionway was located the purser's office, where all passenger and freight transactions were handled.

At the forward end of the passenger cabin was located the gentlemen's smoking room and barbershop, while at the after end of the cabin, the passageway opened out into the spacious and luxuriously appointed ladies' cabin, in which was provided a grand piano. The woodwork up to the level of the clerestory was varnished black walnut, while the deckhead and its beams and arches were finished in white, with assorted gold-leaf decorations. Hand-done woodcarving was much in evidence throughout, and the entire passenger cabin was fitted with thick carpeting. As was usual for the period, bathroom facilities were not provided in the staterooms, and common water closets were the order of the day. Nevertheless, each stateroom did boast "running water", in that reservoirs mounted over the washbowls were filled daily by the cabin stewards, and after that gravity did the rest. The galley was located down on the main deck, and the food (which was of excellent repute) was brought up to the cabin by means of a primitive lift.

Over the years, JAPAN was commanded by some very famous masters. During the 1890s, her skipper was the well-known Capt. R. W. England, and at one stage in their careers, the Anchor Line "triplets" were commanded by three brothers, Captains John Smith, Robert Smith and W. W. Smith. But JAPAN'S most famous master was her very first commander, Capt. Alexander McDougall, he of whaleback fame. In his autobiography, McDougall stated that he helped to design the "triplets", and that they cost $180,000 each, their iron having been rolled in the Philadelphia area. He recalled that they had accommodations for 150 passengers (this must have included those taking "deck passage", without staterooms), and could carry 1,200 tons of cargo on a draft of twelve feet, the maximum depth available in the lower St. Clair River, while they could take 1,400 tons of cargo in areas of deeper water.

"The company had me spend the winter (of 1870-71) in the yards at Buffalo, and that year I came out as captain of the JAPAN, the last of the three launched. The position came to me at the age of twenty-six, and I was justly proud of the recognition. The boat was to leave September 28, 1871, on a Thursday, and she never had a trial trip or her compasses adjusted. We did not get out until the 29th, before daylight Friday morning, and we made four full loaded trips to Duluth; three of these, the last trips made, in thirty-three days and with the highest paid cargo. The rates were eighteen and a half cents to twenty-four and a half cents a bushel for wheat, thus making the highest earnings on freight or wheat cargo known.

"We came out without compass adjustment, and because of our steering wheel, we had great variation of compass. The lakes were fearfully full of smoke from many forest fires (this was the fall Chicago burned), and we could see but little on the lakes. Because of the high rate of freights and the consequently large number of vessels sailing, we were in great danger, so I had a large board triangle made to get the sun or North Star when possible, to learn our compass variation. I kept a lot of empty boxes and barrels on board to throw overboard, with which to get good ranges by turning the ship about and running with two or three of them in range, all of which helped very much. However, the season was very successful and profitable.

"One of the first men I employed when filling the crew for the JAPAN was a second cook whom I always called 'Charlie'. He subsequently became chef on the Anchor Line and, whenever in later years his boat came to Duluth, I would go down to the docks and wind my way to the galley, where 'Charlie' would always have several fresh-cooked prune pies for me. 'Charlie' was famous for those pies and for many years on the lakes, prunes were called 'Anchor Line Strawberries'.. .

"The Anchor Line struck it rich the first season. Wheat was beginning to come to the new port of Duluth from the Red River Valley of Minnesota by rail and there was not enough (ship) cargo capacity to handle it. In those days, the vessels loaded at the outside elevator and people were so honest that half the time, the vessel company kept no tallyman, but took the elevator weights, and as often as not the cargoes overran by a considerable amount.

"The golden time was not to last long. When Jay Cooke failed in 1873 and the Northern Pacific Railroad collapsed, the traffic on the upper lakes dwindled to almost nothing. The next two years, there was not enough (business) to keep the Anchor Line going on the lakes."

In 1872, the Anchor Line, together with the Union Steamboat Company, which was the lake shipping subsidiary of the New York and Lake Erie Railroad (later known as the Erie Railroad), formed a pool service known as the Lake Superior Transit Company. For almost two decades, the L.S.T.Co. would operate a service between Buffalo and Duluth, with calls at major way ports, and the Erie and Western contributed its beautiful INDIA, CHINA and JAPAN to this new service. They remained in their usual colours, but apparently without Anchor Line insignia, and it would appear that, at various times, they wore a black stack with a very wide white band.

In the summer of 1872, Capt. McDougall "was again captain of the JAPAN, running between Buffalo and Duluth. That season, I carried a cargo of iron ore on this passenger boat from Marquette. We put it on by wheel barrows and did the same (unloading it) at Wyandotte; this cargo made the first Bessemer steel in America. Trade was very dull in the fall; the last trip, I loaded wheat in the hold, partly full, and put some flour barrels on top to keep the wheat from shifting. I believe this plan saved the ship from total loss. We had some barrels on deck also.

"Leaving Duluth on November 25th, with the thermometer showing ten degrees below zero, it was the 27th at midnight when we passed Whitefish Point. The weather had moderated and the night was clear. We had been afraid the early cold would freeze the Soo River, but the night gave promise of fine weather, until about five o'clock a.m., on the 27th, when we had the greatest storm I ever experienced, and which gave evidence of being the greatest ever known at the Soo Canal. The high water went over the lock gates and chased the superintendent from his office at the canal.

"The gale caught us below Traverse Island near the mouth of the Soo River, and it blew so hard, with the wind 100 miles or more per hour, that it picked up the water and pushed our boat sideways. We could not get her from the trough of the sea for about two hours, meanwhile drifting towards Crow Cape and expecting to go to pieces. We tried desperately to get her head to the wind. Finally, when near the rocky and hilly shore, the rebound of the wind and water let us go head into the wind. It was one of the happiest experiences of my life, thus getting head to the sea, and we got up into safety until the wind slacked up. It was eighteen degrees below zero then.

"Upon examination, we found 300 or 400 tons of ice on the ship and the flour barrels below deck were as large as hogsheads, rolling about in their own dough, and the underside of our cabin deck was pasted with flour. All the vessels that were outside of Whitefish Point came to grief. The canal lock was full of ice, so we could not get through. We laid the ship up there for the winter. The steamer CHINA, which came in from Houghton, could not get a good place to lay up at the Soo, so we engaged the captain to take many of us back to Marquette, which he did. Some of the men went on foot to Saginaw, and some to Mackinac. There was no railway or telegraph then. We got to Marquette a week before the railroad to Green Bay was connected. There were about 250 men from ships in Marquette waiting for the railway."

As poor business conditions prevailed during 1873, none of the boats of the Lake Superior Transit Company's pool service operated that year, and it is doubtful that JAPAN ran in 1874 either, despite the fact that she was an almost brand new and very popular steamer. In 1875, JAPAN was in service during July and August only, with Capt. McDougall serving as both master and purser, but she then laid up at Buffalo, with poor prospects for the following year. In fact, it was not until about 1878 that business had improved to the point that JAPAN and her two sisterships were back in full commission.

After 1892, the "triplets" reverted to service in the colours of the Anchor Line, for the L.S.T.Co. pool service was dissolved. The three sisterships remained very popular amongst the travelling public, for they enjoyed an enviable reputation for reliable service. JAPAN'S schedule called for her to run between Buffalo and Dulth,[sic] with way calls at Erie, Cleveland, Detroit, Mackinac Island, Sault Ste. Marie, Marquette and Hancock. JAPAN left Buffalo every other Thursday, taking two weeks to make a round trip. INDIA ran the same route on alternate weeks, while CHINA was engaged on the company's route from Buffalo to Chicago. During this period, the trio carried a large red anchor painted on their bows, along with the words "Anchor Line" and sometimes they also sported the words "Pennsylvania Railroad". The anchor later became white, with it and the name of the line superimposed on a red keystone, symbol of the State of Pennsylvania.

By the turn of the century, however, the "gravy days" of the iron-hulled trio were drawing to a close. The Anchor Line was thriving, and the three steamers simply could not carry enough passengers or freight to satisfy the demand. The line was beginning to build a new series of steel-hulled package freighters, and was also drawing up plans for the construction of three large new passenger steamers, which would be 340 feet in length. These new ships were eventually named TIONESTA, JUNIATA and OCTORARA, and they entered service in 1903, 1905 and 1910, respectively. As a result, the older CHINA was retired in 1904, INDIA in 1906, and JAPAN was taken off her old route in 1910. It is possible that each of the older steamers may have operated in a special excursion or cruise service for a short period of time before being sold out of the fleet.

JAPAN, being the last of the trio to have been commissioned back in 1871, was the last of the steamers to be taken out of service, and she followed her sisters in being sold across the border. All three of the vessels were sold to the same Canadian fleet, the Montreal and Lake Erie Steamship Company Ltd., Toronto, which obviously had a liking for that particular class of steamer. CHINA had been renamed (b) CITY OF MONTREAL (I), and INDIA took the name (b) CITY OF OTTAWA, so it is not surprising that, when she crossed the border, JAPAN was rechristened (b) CITY OF HAMILTON (I). Registered at Ottawa, she was given official number C.126526. The Canadian steamboat inspectors remeasured her, and recorded that she was 220.0 feet in length, 32.5 feet in the beam, and 14.0 feet in depth, with tonnage of 1574 Gross and 869 Net.

Soon after her purchase, CITY OF HAMILTON was sent to the Polson Iron Works of Toronto for the replacement of her machinery. Polsons equipped her with a fore-and-aft compound engine, which had cylinders of 22 and 44 inches, and a stroke of 36 inches, and to provide steam she was given two new Scotch boilers that measured 10 feet by 11 feet. By whatever methods of calculation they then applied, the government inspectors concluded that this new machinery produced 89 Horsepower. The other two sisterships also appear to have received similar new engines and boilers when they came under the Canadian flag.

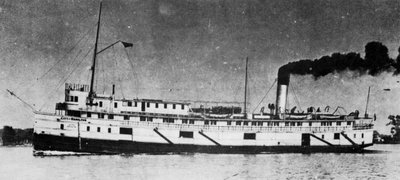

CITY OF HAMILTON was placed in the passenger and freight service between Montreal and Detroit, with calls at major ports, such as Toronto and Hamilton, along the way. The managers of the Montreal and Lake Erie Steamship Company Ltd. were Jaques and Company, Montreal, a family interest which operated the Merchants Montreal Line, a package freight pool service. CITY OF HAMILTON was given the usual Merchants Montreal livery, which included a white stack with a black smokeband. Her cabins and topsides were white, while the hull below the main deck was painted a dark colour, which may have been either green or black. The name "Merchants Montreal Line" was carried in bold letters on the steamer's bows.

One other change altered the appearance of the three sisterships when they came into Canadian registry. Their new operators quite rightly felt that their ornate octagonal pilothouses, although handsome in their day, had outlived their usefulness, and that more modern bridge facilities should be provided for the officers of the vessels. As a result, all three steamers lost their birdcage pilothouses, and hence also the famous statues that formerly had perched thereon, and they were fitted with more modern round-front pilothouses equipped with the usual open navigation bridge above. There were seven windows in the front of each of the new cabins, and the houses themselves were much more spacious than were their predecessors. The monkey's island above the new wheelhouse on CITY OF HAMILTON was surrounded by a high closed wooden rail, on which could be hung a dodger in foul weather. As well, stretcher-frames were provided so that an awning could be spread over the upper bridge in hot weather. Two holes were cut in the front of the closed bridge rail so that the officers on watch could see down to the foredeck.

CITY OF HAMITON, in the livery of the Merchants Montreal Line, is upbound in the St. Clair River in this Pesha Photo, c. 1911.

The year 1913 was one of momentous developments, not only for CITY OF HAMILTON, but also for the entire Canadian lake shipping scene, for it was on June 17, 1913, that Canada Steamship Lines Ltd., Montreal, was incorporated. Numerous mergers of various steamship companies took place in the months preceding the formation of the Canada Transportation Company Ltd., which almost immediately was rechristened as C.S.L. Most of the mergers involved the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company Ltd., which was the largest of the fleets involved in the final amalgamation. Amongst the numerous fleets that were swallowed up in the formation of C.S.L. was the Merchants Montreal Line, and it was in this manner that ownership of CITY OF HAMILTON passed to C.S.L. It was not until about 1915, however, that the actual transfer of ownership from the Montreal and Lake Erie Steamship Company Ltd. was officially recorded.

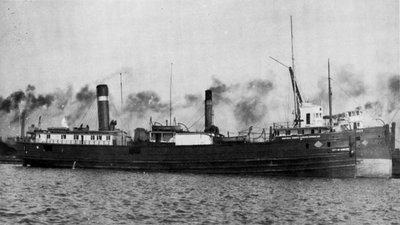

CITY OF HAMILTON and CITY OF OTTAWA were placed on the Montreal-Toronto-Hamilton express package freight route, each of the steamers making a return trip between those ports once a week. They were no longer accompanied by the third sister, CITY OF MONTREAL, for she had sustained damage by fire early in 1913, and had been sold out of her old fleet before the formation of C.S.L. CITY OF HAMILTON and CITY OF OTTAWA did not carry passengers after their acquisition by C.S.L., but they did retain all of their old deckhouses for at least one year. One gentleman who served in the crew of CITY OF HAMILTON during her first season in C.S.L. colours recalled that each of the crewmen occupied his own private cabin that season (a luxury not normally enjoyed by freighter crews of that period), and that this was accomplished by using the former passenger staterooms for crew accommodations.

S.S.H.S.A. Photobank view shows CITY OF HAMILTON shortly after acquisition by C.S.L. Her deckhouses remain but are no longer occupied by passengers.

Very soon, however, both steamers were cut down to a cabin configuration more suitable for their use in the general cargo trade. The pilothouse and the forward end of the main cabin (the section that had formerly housed the gentlemen's smoking room) were retained, the lower house providing the quarters for the senior deck officers, since the texas on the upper deck (and all of the cabins that had, over the years, been added behind it) were removed at this time. The after end of the main cabin was kept to house the galley and crew's quarters, but the entire midship section of the old deckhouse was cut away. Only two of CITY OF HAMILTON'S six lifeboats were retained, and these were carried on the boat deck abaft the stack. The old fidded foremast was removed, and it was replaced by a pole mast which, although tall, was not nearly as high as the original mast. Like its predecessor, the new mast sported a long gaff. A new and very thin mainmast was stepped immediately forward of the after cabin.

During the first few years after her acquisition by C.S.L., and after the company had settled on a uniform paint scheme for its freighters (colours were greatly confused during the first year or so of the fleet's existence), CITY OF HAMILTON wore a red hull, while her deckhouses were painted grey. She carried the letters 'C.S.L.' in white in a diamond on her bows, and on the closed deck rail forward appeared in white the words "Montreal-Toronto-Hamilton Express Line". Her stack was red with a black smokeband, these colours having been taken over from the R & O fleet, although her stack later became red with a white band and black smokeband, as C.S.L. soon adopted the more colourful stack design that had previously been carried by the ships of the old Northern Navigation Company Ltd.

By the very early 1920s, Canada Steamship Lines had decided that its ships would look better with white deckhouses, and accordingly CITY OF HAMILTON took on a more traditional (and appealing) look at that time, her grey cabins having looked a bit unusual, to say the least. At about the same time, the ship was given a small wooden "doghouse" for additional crew's quarters; it was built on deck about half-way between the bridge structure and the after cabin. As well, her lifeboats were, at this time, removed from the upper deck aft, and they were relocated on the spar deck, between the forward cabins and the doghouse.

Seen at the old Century Coal Dock, Cherry Street, Toronto, in the mid-1920s are CITY OF HAMILTON and ADVANCE.

CITY OF OTTAWA and CITY OF HAMILTON remained together on the lower lake express service until the mid-1920s, providing a relatively fast and reliable scheduled service, but eventually they were replaced by a new fleet of steel "City" class package freight canallers. These new steamers were much faster than the older ships, and their cargo capacity was considerably greater, so it is not surprising that the usefulness of the iron-hulled vessels was nearing its end.

In 1927, a new CITY OF HAMILTON (II), built at Midland, was commissioned and so the old CITY OF HAMILTON (I) was renamed (c) CITY OF WALKERVILLE. The new name was appropriate, in that the older vessel was transferred to a new service which operated between Montreal and Windsor. This route did not last long, however, for C.S.L. soon began a "through" package freight service, on which canal-sized package freighters ran from the lower lakes right up to the Lakehead, and thus the shorter route to Windsor was no longer necessary, for the steamers of the "through" service would call there. As a result, CITY OF WALKERVILLE was withdrawn from service, and was laid up at Kingston.

In 1928, CITY OF WALKERVILLE was acquired by Toronto contractor and marine entrepreneur John E. Russell, and he had her towed to Toronto, where she was cut down to a barge by the Toronto Dry Dock Company Ltd. This rebuilding reduced her tonnage to 1239, both Gross and Net. Russell transferred CITY OF WALKERVILLE back to U.S. registry, and she was given back her original name, thus becoming (d) JAPAN, with her original official number restored. Her ownership was transferred to the Ohio Tankers Corp., which was managed by Capt. C. D. Secord, and her home port became Cleveland. In fact, the 1930 issue of "Merchant Vessels of the United States" indicates that her registered owner at that time was Carl D. Secord.

In 1928, shortly after her transfer to U.S. registry, JAPAN was taken in hand by the Buffalo Shipbuilding Company, which rebuilt her as a tanker barge. It in interesting to note that, although JAPAN had an iron hull, she had always had a wooden main deck, and she retained this even after her conversion to a tanker. Modern steamboat inspectors would, no doubt, be shocked to learn that such a remarkable situation was allowed to exist I

JAPAN was returned to the ownership of John E. Russell in 1932, and she was brought back into Canadian registry as (e) ROY K. RUSSELL. She was named for Roy Kitchener Russell, one of the many sons of John E. Russell. It should be noted that the famous John Russell, who was involved in marine and shoreside contracting, ship repair and construction, marine salvage, and vessel ownership, perished aboard one of his own vessels when, on July 23, 1934, the old barge EN-AR-CO blew up at Toronto whilst being refitted for service in the Lloyd Tankers fleet. Considering that she had a wooden deck, it is somewhat surprising that ROY K. RUSSELL managed to avoid the same gruesome fate.

In any event, Russell chartered ROY K. RUSSELL to Lloyd Tankers Ltd., which was the lake shipping subsidiary of Lloyd Refineries Ltd., Toronto and Port Credit. The barge, at that time, had an open bow with a small forward cabin whose sides were extended out to the vessel's hull plating just short of the bow. She had a small donkey engine for towing purposes, and so a small stack protruded from this forward cabin, and it was painted silver with a black top. Aft, the RUSSELL carried a small, squarish cabin of wooden construction, and atop it perched a small and somewhat backwards-leaning pilothouse, which may actually have been an adaptation of the pilothouse that the ship carried back when she was a steamer. (In fact, when she was the barge JAPAN, she was still carrying her old pilothouse - minus the upper bridge - as well as the old texas, up through which the new forward stack protruded.) ROY K. RUSSELL had her cabins painted white, and her hull was red for Lloyd Tankers service.

The RUSSELL was normally used to carry crude oil from Montreal East to the Lloyd refinery at Port Credit (located just to the west of Toronto), and she was usually towed by the big wooden steam tug MUSCALLONGE. After her construction in 1935, the steel barge BRUCE HUDSON joined the RUSSELL on the Montreal - Port Credit service MUSCALLONGE towed the two barges in tandem down Lake Ontario, and the small, shallow-draft tug AJAX was dead-headed along with the tow. The condition of ROY K. RUSSELL's venerable iron hull was such that she could not get a certificate for anything but Lake Ontario service, and the inspectors would not let her venture down the St. Lawrence Canals. As a result, she would be left at Prescott, and as the MUSCALLONGE was too big to transit the canals with BRUCE HUDSON, she would stay at Prescott with the RUSSELL.

AJAX would take BRUCE HUDSON down to Montreal East, and would return with a cargo that would be off-loaded into the RUSSELL at Prescott. AJAX would return with the HUDSON to Montreal, where the barge would again be loaded, and she would then bring her back up again to Prescott, where the tow would be formed up, with MUSCALLONGE in the lead, the RUSSELL as the first barge, the HUDSON behind her, and AJAX, dead tug, out on the string astern. The latter position was necessary, as the little AJAX had only a very small capacity for bunker oil, and she could not carry enough fuel for her to help with the lake tow.

The arrangement with BRUCE HUDSON and ROY K. RUSSELL, however, was frought with problems. The HUDSON capsized in Lake Ontario off Cobourg on July 16, 1935, and, although rescued and later righted, she was again in trouble on the lake during November, at which time she was rescued by the freighter BRULIN. And, as it turned out, 1935 was the last season on the lakes for the RUSSELL.

During adverse weather conditions which set in late in the 1935 season, ROY K. RUSSELL broke her lines whilst moored at the Port Credit refinery. She had her antiquated mushroom anchor down, but it simply dragged along the shale bottom, and the RUSSELL drifted onto the rock ledge located at the mouth of the Credit River. Her cargo of crude oil was salvaged, but the barge herself remained hard aground and was frozen in for the entire winter.

July 1935 photo by J. H. Bascom shows ROY K. RUSSELL and tug RIVAL engaged in efforts to right the overturned barge BRUCE HUDSON at Toronto.

Salvage operations were begun in April of 1936, and the little tug AJAX, which could venture over the shoal without going aground herself, finally succeeded in refloating ROY K. RUSSELL that spring. Nevertheless, considering the fact that her condition was such as to limit her to Lake Ontario service during 1935, it goes without saying that the steamship inspectors took an extremely dim view of her condition in 1936. Her bottom was in such deplorable condition after the grounding that repairs could not be considered economical.

Accordingly, she was stripped out at Port Credit, anything useful being removed by the crews from Lloyd Tankers. Then, in July of 1936, the tug MUSCALLONGE took ROY K. RUSSELL in tow one last time. She hauled her over to Hamilton, and there the barge was broken up for scrap. It is interesting to note that MUSCALLONGE herself did not long survive ROY K. RUSSELL, for she was grounded near Brockville on August 15, 1936, after a fire broke out in her galley, and she was totally destroyed where she lay.

Ed. Note: Of assistance to us in the preparation of this feature was The Autobiography of Captain Alexander McDougall, published in 1968 by the Great Lakes Historical Society. A description of the interior of the "triplets", along with two photos of JAPAN'S interior, appeared in Dana Thomas Bowen's Memories of the Lakes, which was first published by the author in 1946.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.