Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| Resolute Revisited | |

| Lloyd Pierce | |

| Lay-up Listings - Winter 1982-83 | |

|

Ship of the Month No. 117 Midland City | |

| Table of Illustrations |

In our "Ship of the Month" feature of the January issue, we mentioned that we sometimes find ourselves in the position of wanting to present the story of a particular ship, perhaps at the request of one or more of our members, but are unable to do so because of the need to obtain considerable further information in order to produce a complete and accurate history. If we lack only one small item of detail, we may go ahead with the feature and include a request for assistance in running down the missing data.

But sometimes we are missing so much detail that there is no point in going ahead with the story until we have been able to research the whole matter, for we wish to preserve our reputation for accuracy. A case in point concerns the famous Georgian Bay passenger steamer and motorship MIDLAND CITY. We have wanted to feature her in these pages, having received several requests to do so, but could not put her story into print until we had more information available. That time has now arrived, so, if we can set our clocks back one hundred and thirteen years, we will pick up the story of MIDLAND CITY at its beginning.

One of the best known early steamship operators on Lake Ontario was Charles F. Gildersleeve of Kingston, Ontario. In the years following the mid-point of the nineteenth century, shipping was growing very rapidly on the lake, but there were no shipyards in the vicinity that could turn out vessels built with the metal hulls that were then coming into fashion. Back in 1864, Gildersleeve had wanted to build an iron-hulled sidewheel passenger steamer and had gone to shipbuilders in Glasgow, Scotland, for the vessel, which was eventually christened CORINTHIAN. Constructed at Glasgow, she was taken down and her hull and frames were shipped across the Atlantic and reassembled at Kingston. Her cabins were added there, while her engine and boiler were made for her at Kingston by the Canadian Engine and Locomotive Company.

In 1870, C. F. Gildersleeve again found himself in need of another steamer for Lake Ontario service. Once again, he went back to the same Scottish builders and had them construct another iron hull for him. This hull was duly completed and was knocked down, shipped out to Canada, and reassembled at Kingston in 1871. It was there that her cabins and machinery were added in the same manner as had been those of CORINTHIAN earlier. The reassembling completion of the new steamer was done by George Thurston at the Davis Shipyard, which was located at the foot of Union Street in Kingston.

The new vessel was given a length of 114.0 feet (120.0 feet overall), and a depth of 6.0 feet. Her hull was 19.0 feet in width, but she sported a beam of 32.0 feet over the guards. Her original Gross Tonnage was 293. Her feathering sidewheels were turned by an inclined tangent compound engine with cylinders of 20 and 36 inches (the high-pressure cylinder has also been reported as having a diameter of 18 inches) and a stroke of 36 inches. Steam was provided by one firebox boiler which measured 7 1/2 feet by 13 feet.

The steamer was launched on August 16, 1871, and was named MAUD. The christening was performed by Miss Maud Gildersleeve, daughter of Charles F. Gildersleeve, and her selection for the task was most appropriate in that the vessel was named for her. The next day's edition of "The Kingston News" reported that Miss Maud "took her place at the bow of the boat and grasped the gaily ribboned bottle with which the baptismal ceremony was to be consummated. Amid plaudits, the new vessel left her cradle as the official spirits, manfully, dashed the bottle against the bow." The wording of this amusing little quotation leads us to wonder whether the reporter might not also have been dashing some spirits.

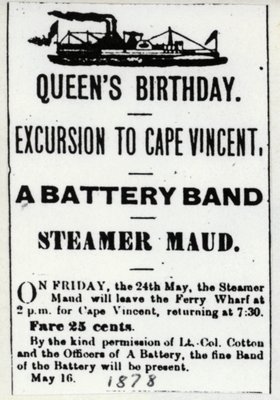

Although heavily retouched, this is the only photo of MAUD that we have ever seen. Courtesy Marine Museum of the great Lakes at Kingston.

MAUD was a rather interesting little steamer. Her main deck was fully enclosed, with two large gangways on either side. No doubt the forward one would have been used for loading small amounts of freight for local destinations. The after end of the main deck sported large observation windows and it is likely that, in typical fashion of the day, MAUD carried her dining saloon there. The promenade deck was generally open, except for a small cabin. A large lifeboat was carried on each side of the promenade deck, just above the paddleboxes. The forward end of the deck was fully open but an awning could be spread to shelter passengers from the heat of the sun or from inclement weather. The after end of the deck was covered by the hurricane deck above.

On the top deck was located the pilothouse, an octagonal "birdcage" cabin positioned just forward of the paddleboxes. Abaft the pilothouse rose the MAUD's tall black stack, which was totally bereft of any rake whatever. Likewise without rake was her sole mast, a fairly short pole which was set immediately forward of the pilothouse and directly in the centre of the wheelsman's line of sight. An extra lifeboat was carried upside-down on the hurricane deck abaft the stack.

With her hull and cabins painted a gleaming white, MAUD was placed in service and assigned to a route which took her from Kingston to the various ports of the Bay of Quinte. She ran that service for the remainder of the 1871 season and on into the summer of 1872, but her career in Gildersleeve colours was to be short. Her owner was said to have been disappointed with MAUD's performance, and we take this to mean that C. F. Gildersleeve had expected the engine to produce a better speed for the ship.

As a result, Gildersleeve sold MAUD in 1872 to the Folger Brothers for their St. Lawrence Navigation Company. Henry Folger and his brother, natives of Cape Vincent, New York, ran their shipping business out of Kingston. With their other steamers PIERREPONT and WATERTOWN, the Folgers operated a route from Kingston to Gananoque and then across to Clayton, N.Y., Thousand Island Park, Alexandria Bay and Rockport. They also operated a direct service from Kingston to Cape Vincent, and it was to this route that MAUD was assigned. If Gildersleeve did not consider MAUD to suit his requirements, the Folgers appear to have been quite satisfied with her performance, and she served their fleet, without any major alterations, for over two decades, after which she was rebuilt and returned to service.

1878 Excursion advertisement

It was in 1884 that MAUD carried her most famous passengers, albeit under particularly sombre circumstances. Dileno Dexter Calvin, who was born in 1798 and was the founder of the Calvin Company's empire on Garden Island, near Kingston, passed away on May 18, 1884. A native of Vermont, he had lived at Clayton before coming to Garden Island about 1835, and it was not surprising that he was taken back across the river after his death. MAUD was the steamer selected to take D. D. Calvin home. "The Daily British Whig" of May 21st, 1884, reported in part as follows:

"Yesterday afternoon, the funeral of the late D. D. Calvin took place from his residence on Garden Island to Clayton, via the steamer MAUD. The boat left the ferry wharf at 12:45, having on board the principal public men of the city... When the MAUD reached Garden Island, the dock was crowded with people... When the MAUD was ready to start, she had on board about 200 persons, and the CHIEFTAIN (the second Calvin tug of this name), a short distance behind, carried most of the inhabitants of the Island. The boats reached Clayton about four o'clock. The funeral cortege was again formed... The pallbearers were Sir John A. Macdonald, Hon. G. A. Kirkpatrick, A. Gunn, M.P., J Fraser, Col. Kerr, J. Richardson, J. B. Walkem and W. Ford..."

The late D. D. Calvin was a most important person indeed, but he was not the most distinguished passenger carried by MAUD that day. One of the pallbearers was the Rt. Hon. Sir John Alexander Macdonald, who was at that time the Prime Minister of Canada. In fact, he was Canada's first Prime Minister, having taken office first in 1867, the year of Canadian Confederation. He served from 1867 until 1873, and again from 1878 until 1891.

In 1894, the Folgers decided to rebuild MAUD so as to increase her passenger capacity and make her a more suitable running-mate for the larger boats of the fleet. Accordingly, she was returned to the Davis Shipyard at Kingston, and there was reconstructed during the winter of 1894-95. During the course of the rebuilding, her iron hull was sheathed with wooden planking in order to fit her for service in the St. Lawrence River rapids; the sheathing was designed to minimize damage to the hull plating in the event the ship touched any of the rocks in the rapids.

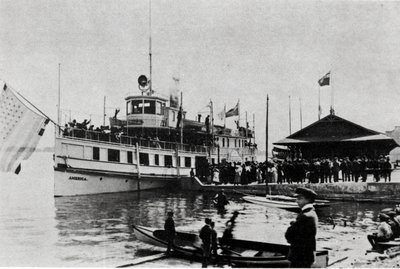

The vessel emerged from the rebuild with a length of 153.2 feet, a beam over the guards of 33.2 feet, and a depth of 6.4 feet, these dimensions giving her tonnage of 553 Gross and 287 Net. The lengthening permitted her to be licenced for 600 passengers, a considerable increase over her previous capacity. The steamer was given a new name at the time of her transformation; rechristened (b) AMERICA, she was enrolled at Kingston with official number C. 100662. In fact, this was the first time that she ever carried an official number, for she had been built before the implementation of Canadian registry requirements, and was not assigned a registry number when she was launched as MAUD back in 1871.

When AMERICA was returned to service in 1895 for Folgers' St. Lawrence River Steamboat Company Ltd. of Kingston, operating between Clayton and Montreal, she was a much more modern and impressive vessel than she had been in earlier years. Her main deck cabin was, of course, much larger; the forward portion of it was open for observation purposes but the large ports there could be closed with wooden shutters in the event of inclement weather. AMERICA seems to have been fitted with larger paddlewheels during her rebuild, for she now carried higher paddleboxes, whose rounded tops protruded upward into the sides of the promenade deck cabin.

A most interesting view of AMERICA comes to us from the collection of the late Willis Metcalfe, courtesy of Lorne Joyce.

The promenade deck itself was more spacious now and could accommodate a larger cabin. The deckhouse extended out to the sides of the ship amidships, but its forward and after ends, both of which were fitted with large windows, were recessed to allow open deck space around them. The aft part of the promenade deck was covered with a solid roof and the forward end was fitted with stretchers on which a fancy awning could be hung. During the rebuild, the lifeboats had been removed from this deck and relocated on the hurricane deck. They were now four in number and were placed two on each side, forward and aft of the cabin area so that they could be dropped to the level of the open sections of the promenade deck and loaded there in case of emergency. The davits were of the radial type but did not have rounded tops; instead, in a somewhat old-fashioned style, they had short "gaffs" which extended out parallel to the deck, about a third of the way down from the top of the davit, and it was from these that the boats were suspended.

A new pilothouse and cabin containing officers' quarters were set at the forward end of the boat deck. Both were rather fancy pieces of the joiner's art, with large squared frames holding round-topped windows, and with the cabin sides decorated with inset panels. The pilothouse itself had five very large windows in its front, and its front corners were set off on angles so that it actually had five sides plus its back wall. A large and fancy nameboard was hung on the boat deck railing immediately forward of the pilothouse.

AMERICA still carried a stack and single mast with little, if any, rake. The stack, which may well have been the same one she carried as MAUD, was located immediately abaft the boat deck cabin, while the mast, somewhat taller than her original and fitted with a slender topmast, sprouted from the pilothouse roof. An immense carbon-arc searchlight was placed atop the pilothouse, this navigational aid seeming far out of proportion in size.

AMERICA'S boat deck appeared at first glance to be a veritable forest of poles of one sort or another. In addition to the four davits on either side of the ship, she carried a tall pole aft from which she flew her ensign. As well, she carried sidepoles on which she flew other bunting. At the stem, she sported a tall, ball-topped steering pole and a jackstaff which, rather peculiarly, protruded far out from the bow at an angle of about 45 degrees to the water. Many photos of AMERICA show her carrying on this staff an enormous U.S. flag, one so large that it nearly touched the water.

AMERICA remained much the same in her appearance not only through the remainder of her years of service for the Folgers, but also for most of the rest of her life, as long as it was. She received minor alterations at Kingston in 1899, and these resulted in a revision of her registered tonnage to 521 Gross and 266 Net, but the work done at that time did not materially alter her appearance in any way.

Although AMERICA was owned by the St. Lawrence River Steamboat Company Ltd., the Folgers operated her in their "American Line" of Cape Vincent, N.Y. In 1898, they commenced running her, along with EMPIRE STATE and NEW YORK, to Montreal from Kingston, with way stops at various Thousand Island ports. But, on July 15, 1898, the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company Ltd., which had long enjoyed an enviable supremacy on through passenger services on the St. Lawrence River, declared war on the American Line. The R & O placed COLUMBIAN and CASPIAN on the Thousand Island Route in direct competition with the Folger boats, and cut their fares to lure away passengers.

The R & O had a monopoly on the through route from Toronto to Montreal and hence did not cut rates on its connecting lines down the river, but it did directly engage the Folgers in a rate war in the local Thousand Islands trades, in so doing going into routes which had hitherto been left almost entirely to the Folgers. This was all done solely because the Folgers had dared to challenge the R & O on the Kingston-Montreal route. To make matters even worse, the Folgers managed to secure the support of the New York Central Railroad, which began to issue through tickets to Montreal via the American Line steamers.

For several months, the two companies engaged in one of the most cut-throat rate wars ever seen on the lakes. Each strove to defeat the other, either by introducing competitive routes or by chopping fares to the point where the carrier could not hope to make a profit but only to carry more passengers than the opposition. R & O told its captains to take passengers even at sacrifice rates, while the Folgers started a daily service in an area operated every other day by R & O. The Richelieu and Ontario cast aspersions on the facilities offered aboard the Folger boats, and the American Line immediately announced that it would compete with the R & O on its eminently successful Saguenay River cruise run. In short, the two lines were killing themselves simply to gain the upper hand on the local Thousand Islands services, only a relatively small territory being in question.

This rate war amounted to lunacy in the extreme, and both companies soon awoke to the fact that the only beneficiaries of the dispute were the passengers who could appear on a wharf and command whatever price they wished to pay for the privilege of riding one of the boats, while the lines saw revenues dip toward the point beyond which they would be unable to operate at all. With great relief, "The Railway and Shipping World" issue of June 1899 stated that "there is no passenger war on the St. Lawrence River this year, the R.& O.N.Co. handling the through business exclusively, and the Folger boats attending to the local Thousand Islands business. The Folger fleet consists of the strs. NEW YORK, EMPIRE STATE, AMERICA, ST. LAWRENCE, NEW ISLAND WANDERER, ISLANDER and JESSIE BAIN."

Thus the AMERICA, with all flags flying as usual, survived the rate war and held on to her old route, providing a local service rather than a through connection, and doing so very successfully. On May 2, 1911, AMERICA passed an inspection of her boilers and machinery and was declared fit to continue her run, which at that time took her from Trenton, Ontario, to Montreal via innumerable way ports.

In 1912, the Thousand Island Steamboat Company, another enterprise of the Folger Brothers, placed an order with the Toledo Shipbuilding Company for the construction of a new steamer for the Thousand Islands route, one that would be eminently suited for the sightseeing service that had "become so popular. The new boat was 166.4 feet in length; the shipyard's Hull 123, she emerged as THOUSAND ISLANDER (U.S.209906) and was registered at Cape Vincent, N.Y., in order to comply with the new coasting requirements regarding vessels travelling between U.S. ports, as the river steamers were then doing.

That same year, the St. Lawrence River Steamboat Company Ltd. was acquired by the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company Ltd., Montreal, and at last all the major services in the Thousand Islands were brought under the control of one firm. In the following year, 1913. the R & O itself was swallowed up in the formation of a large new corporation, which was first called the Canada Transportation Company Ltd., Montreal, but whose name was soon changed to Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. Thus the veteran AMERICA became part of the largest fleet ever to sail the lakes under the Canadian flag.

C.S.L., however, had a plethora of passenger steamers available to it, considering the number of fleets that had been merged into the new company, and it also had the new THOUSAND ISLANDER in service on the river. As well, motor launches were beginning to syphon off much of the available tour traffic and, as a result, the aging boats of the "Great White Fleet" were considered redundant and were put up for sale. AMERICA and NEW ISLAND WANDERER were fortunate in that they were still in sufficiently good condition to be saleable at that time. Nevertheless, C.S.L. continued to operate AMERICA, holding her in the fleet through the 1920 season.

We now change our sights and look to the Georgian Bay service provided by C.S.L.'s Northern Navigation Division. The company operated the steel-hulled steamer WAUBIC, built at Collingwood in 1909, over a route from Penetanguishene to Parry Sound, but gave up the route at the close of the 1920 season. WAUBIC was then sold to the Rockport Navigation Company Ltd., Kingston, of which R. H. Carnegie was manager, and, with only minor alterations, she was placed on the ferry service between Kingston and Cape Vincent, with ongoing service as far as Clayton. WAUBIC served that route until 1932, and ran for two further years from Kingston to Clayton with no stop at Cape Vincent.

When WAUBIC came off her Georgian Bay route at the end of the 1920 season, local residents realized that there was considerable potential for a service to area ports. A Midland group, headed by James Playfair, was among the believers and jumped into the vacuum left by the departure of WAUBIC. The new group formed a corporation known as the Georgian Bay Tourist Company of Midland Ltd. and, either late in 1920 or early in 1921, it purchased AMERICA and took her to the yard of the Midland Shipbuilding Company Ltd. (another of Playfair's many shipping enterprises) for reconditioning.

The new owners readied AMERICA for the Georgian Bay service in 1921, and it was originally intended that she be renamed CITY OF MIDLAND for her new duties. However, in order to avoid an unpleasant association with the old Northern Navigation steamer CITY OF MIDLAND which had burned at Collingwood on March 17, 1916, AMERICA was instead renamed (c) MIDLAND CITY in 1921, and was reregistered at Midland. Her predecessors on the Parry Sound route, namely WAUBIC and, before her, CITY OF TORONTO, had used Penetanguishene as their southern terminus, but MIDLAND CITY's new owners were firmly established in Midland and it was obvious that Midland, being a larger and more enterprising community, should be the home base of the new service.

One of the members of the group that purchased MIDLAND CITY was a gentleman by the name of Newton K. Wagg, who owned a steam laundry in Midland and operated a small boat to pick up and deliver laundry to the summer hotels and cottages located around Georgian Bay. Wagg became the manager of the new company, and operated MIDLAND CITY quite successfully on the new route that took her out amongst the Thirty Thousand Islands. Business was booming and so many summer visitors and cottagers wanted to ride in to Midland on the "laundry boat" that the company also purchased the small steamer CITY OF DOVER, from W. F. Kolbe of Port Dover, Ontario, and put her on a route between Midland and Honey Harbour. CITY OF DOVER was actually owned by the Honey Harbour Navigation Company Ltd., which was a subsidiary of the Georgian Bay Tourist Company. Newton K. Wagg took over as president of the entire concern in 1926 and the fleet soon numbered five vessels, including not only MIDLAND CITY and CITY OF DOVER, but also the small steamers WEST WIND and WATERBUS as well as the barge IMPERIAL. The latter was the former steamer SOVEREIGN and had been bought to run for the Georgian Bay Tourist Company. After arriving at Midland, her machinery failed to pass inspection and she apparently was used briefly as a barge before being scrapped.

But all was not sweetness and light for MIDLAND CITY which, incidentally, still looked very much as she had when on the St. Lawrence River. After the close of the 1923 tourist season, her third on Georgian Bay, MIDLAND CITY was laid up for the winter at her usual berth in Midland harbour. On October 27, 1923, her engineroom crew was working on her machinery and had opened her lower portholes for ventilation. Her fender strake was resting on the rub rail along the side of the wharf and, when the vessel rolled in waves produced by a sudden thunderstorm, she began to take on water through the open ports and soon settled to the bottom. She came to rest on an almost even keel, submerged up to the promenade deck forward and the boat deck aft. The Burke Towing and Salvage Company Ltd. sent equipment from its plant, which was located but a few hundred yards away, and soon managed to close MIDLAND CITY's engineroom ports. They pumped out the hull and refloated the steamer without undue difficulty.

The Georgian Bay Tourist Company made but little change in MIDLAND CITY during the first few years that it operated her. She retained her white hull and cabins, with black trim, and her stack was white with a black smokeband (although it briefly also sported a black bottom). Her hull colour was occasionally changed from white to black, although it was mostly white.

Other changes to MIDLAND CITY in her early years on the Bay involved the removal of the forward lifeboat on each side and the fitting of a short and very thin mainmast. This small pole mast served her for only a few years and had disappeared by 1933. The foremast remained just as it had been earlier, complete with its somewhat anachronistic topmast. As well, the promenade deck cabin was extended aft to provide more sheltered space.

This photo, taken late in the career of MIDLAND CITY, illustrates her appearance after her dieselization in 1933

During 1933, her owners decided that the venerable MIDLAND CITY required some updating in order to keep her operating profitably. At the close of the navigation season, she was taken around to the Midland shipyard and there her old steam engine was removed, along with her boiler and sidewheels. In their place were fitted two Canadian-built Fairbanks-Morse diesel engines which were connected to newly-installed twin propellers. It was at this time that she was given a new and much shorter stack, placed somewhat further aft than had been her old funnel.

The reconstruction gave MIDLAND CITY a rather greater tonnage, her Gross increasing to 580 and her Net to 476. In the process of the rebuilding, she lost her melodious steam whistle that had become so well known as it echoed amongst the islands of the Bay. In its place, an air horn was mounted on the new stack. But MIDLAND CITY's familiar voice was not all that she lost. After the rebuild, she no longer emitted the clouds of black smoke that, in years past, had formed a trail as she wound her way through the island channels. This smoke trail had served to provide cottagers and visitors alike with a clear signal as to just how much time they had to make their way down to their local dock in order to catch the boat.

But MIDLAND CITY's appearance was not altered all that extensively despite the new stack and the loss of her paddlewheels, apart from the fact that her tall foremast was removed and replaced by a short pole that hugged the after wall of the pilothouse. (Both this new mast and the stack were well raked.) The vessel was still very much of an antique, with her panelled woodwork and her fancy old pilothouse. She still did not have a visor around the front of her pilothouse, nor would she to the end of her days. Instead, a large curved canvas awning was hung out over the pilothouse windows to shade the view of those on watch. She also retained on her hull the wooden sheathing which had been fitted to shield her plates from damage in the St. Lawrence rapids. The planking was kept to protect her from scrapes in the narrow channels to which her Georgian Bay service took her.

On one particular occasion, however, her planking could not keep MIDLAND CITY from suffering an embarrassing accident. Navigation in the channels of the 30,000 Islands was always difficult, even in the days before the proliferation of small power boats, and navigational aids were not as common as they are today. (It was only in later years, when recreational boaters were successful in having the federal government deepen the channels and provide accurate charts, that the task of sailing those waters became less arduous.) It was near the close of MIDLAND CITY's first summer as a motorship that she encountered the most serious accident of her career, one which might have had very grim consequences indeed for the boat and her passengers.

On August 26, 1934, MIDLAND CITY was out on one of her special Sunday sightseeing trips through the islands, with some 150 passengers aboard. Present Island lies on the eastern shore of Georgian Bay, some two miles from Moore Point and near Beausoleil Island, a national park; Present Island is surrounded by shoal water and navigation in the area has always been very hazardous. It certainly proved so to MIDLAND CITY, which got too close to the Island and ran foul of one of its shoals. After striking the bottom, the boat began to make water and settle by the stern. Her master ordered all passengers to the bow and immediately headed the vessel toward shore, a mile and a half off to the southwest. MIDLAND CITY could not make it all the way in to shore and ran up on a sandbar off Sucker Creek Point, a rather remote area which, although only five miles north of Midland, boasted no roads or cottages.

The stern of MIDLAND CITY settled on the bottom but, as she had run well up on the sandbar, the vessel came to rest with her stern well submerged and her bow pointing high in the air, her forefoot and a large portion of her bottom exposed to view. The lifeboats were launched but there was so little water between MIDLAND CITY and the shore that most of the passengers were able to wade ashore, the adults carrying the children to safety.

MIDLAND CITY had come to rest at such a peculiar angle that her plight was soon noticed by pleasure boaters in the area. Evening was coming and the ship's company lit bonfires on the shore, these fires attracting enough motorboats to the scene to transport all of the passengers back to Midland. There were no injuries in the stranding and most of those involved appeared to consider the event a truly exciting adventure.

The Burke Towing and Salvage Company Ltd. was soon summoned to the scene of the accident to retrieve MIDLAND CITY. The salvors patched the hole in the vessel's stern, cofferdammed the wreck, and pumped her out. MIDLAND CITY was afloat again on September 6, 1934, ready for the tow back to Midland. She was then repaired and was ready to resume service in the spring of 1935.

During her thirty-four summers of Georgian Bay service, MIDLAND CITY regularly ran between Midland and Parry Sound. She would tie up overnight at the Parry Sound municipal wharf, departing at 6:00 a.m. She stopped at the Rose Point Hotel, then would proceed out through the swing bridge and down the South Channel, between Parry Island and the eastern shore of the Bay, to Sans Souci, arriving at this small summer community at 7:00 a.m. Leaving Sans Souci shortly thereafter, she would call at Copperhead, Manitou, Wah-Wah-Tay-See, Go Home Bay, Whalen's, Minnieognashene and Honey Harbour, arriving back at Midland around noon. After the arrival at Midland of the Toronto boat train, MIDLAND CITY would depart again at 2:00 p.m. for the return trip. On this outbound leg of her trip, she would carry the milk, bread, ice cream, groceries, beer and all assorted commodities so essential to the summer hotels and cottages.

The Georgian Bay Tourist Company continued to operate the aging MIDLAND CITY through the Great Depression and on through the Second War. She was more than just a popular excursion boat and a familiar sight as she made her rounds; she was a vital link between the cottage communities and the facilities that were available in Midland. The management of the company changed in 1949, however, when Thomas McCullough became the principal shareholder. As a result of pending labour problems, McCullough put MIDLAND CITY and CITY OP DOVER up for sale. The two vessels were purchased for $50,000 by a Penetanguishene group which formed a new firm known as Georgian Bay Tourist and Steamships Ltd. The new company continued to operate both vessels, and enjoyed a very successful 1949 season, with the tourist business in the Midland area profiting from the tercentenary celebrations of the Martyr's Shrine at Fort Ste. Marie.

But profitable businesses always attract competition, and the new company found itself with opposition invading its territory in the form of the little WEST WIND (which had once run with MIDLAND CITY) and the converted fairmile COASTAL QUEEN, owned by Capt. John Cowan. After the success of 1949. business was bound to drop off in 1950, and this proved to be the case. The opposition boats left the scene, while MIDLAND CITY and CITY OF DOVER carried on alone. Trouble was, however, brewing for the company.

In the early morning hours of September 17, 1949, the C.S.L., passenger steamer NORONIC had burned at her Toronto wharf. As a result of the great loss of life occasioned in this disaster, the authorities quickly implemented new safety measures for passenger boats flying the Canadian flag, and especially for those with wooden superstructures. MIDLAND CITY was hit by the new regulations, and the steamboat inspectors demanded the installation of steel bulkheads and much costly fire retardant and extinguishing equipment. Her owners could not justify the spending on MIDLAND CITY, at her advanced age, of the large sums of money that the required work would involve. By installing a high-pressure sprinkler system, however, they were able to secure permission to keep MIDLAND CITY running until the close of the 1953 season.

In the spring of 1954, the Department of Transport denied permission for MIDLAND CITY to run unless she complied with all of the new regulations. Compliance was impossible and the company reluctantly decided to abandon operations. MIDLAND CITY's furnishings were put up for sale as she lay at her Midland dock, and the boat lay idle throughout 1954. In 1955, after her machinery and any equipment of value had been stripped out, MIDLAND CITY was towed out into the Bay off Tiffin, just outside Midland harbour, and was deliberately set on fire. Her handsome wooden superstructure was quickly destroyed and the hull was towed to an inlet just above the mouth of the Wye River, where it was abandoned. Divers report that the venerable iron hull still lies in twelve feet of water, the bow headed in toward the shore.

And so, MAUD/AMERICA/MIDLAND CITY was laid to rest after eighty-four years on the lakes and the St. Lawrence River. Despite the original complaints of C. F. Gildersleeve concerning her performance, she could not have been expected to serve any better than she did for so many years, and the fact that she survived so long is a credit to her Clyde shipbuilders and to the crews of the Davis shipyard at Kingston who put her together.

Ed Note: We are grateful to James M. Kidd for the extensive research which he did in preparation for this article. We appreciate the assistance of the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston in providing a photograph of MAUD and material written by Elmer Phillips of South Royalton, Vermont. The quote re MAUD's launch comes from Great Lakes Saga by Anna G. Young, 1965, while the report of the Calvin funeral is from The Story of Garden Island by Marion Calvin Boyd, and the notes of Margaret A. Boyd, its editor, 1973.

Previous

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.