Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| Segwun in 1983 | |

| Ship of the Month No. 120 Pontiac (I) | |

| More About Whalebacks | |

| Table of Illustrations |

There are a number of reasons why we choose certain vessels to be featured in these pages. Some are ships that were particularly well known but others are chosen because their stories are unusually obscure. Sometimes we pick out a vessel because she was peculiar in design or served in an unusual capacity at some stage of her lifetime. We occasionally choose a boat because she enjoyed a long and successful career, but others are featured because their lives came to sudden and untimely ends as a result of accidents.

Unfortunately, the steamer that we have chosen to highlight this month falls into the latter category. In fact, not only did she meet her fate under violent circumstances, but she fell victim to another accident much earlier in her career. Perhaps, however, we should not really class this earlier occurrence as an accident, for it was so close to being deliberate in nature that there are few other such incidents recorded in the annals of lake shipping that could match it.

The active fleet of the Cleveland-Cliffs Steamship Company has today shrunk to the point where the company is regularly operating only one or two vessels. This was not always the case, however, and up until just a very few years ago, the Cliffs fleet was both large and influential. It is, of course, to be hoped that the company's fortunes will improve to the point that its earlier stature can be regained.

The original company, the Cleveland Iron Mining Company, was established in 1849 and it became a vessel owner and manager in 1867. Two of its stockholders were Marcus A. and H. M. Hanna, who organized the Cleveland Transportation Company in 1874 to haul iron ore for the C.I.M.Co. This new fleet was to become known as "The Black Line", for its ships were the first lake carriers to sport hulls that were painted black. The Cleveland Transportation Company went out of existence in 1889, when its vessels were sold to the Orient Transit Company, of which A. C. Saunders was manager.

In 1890, however, the Cleveland Iron Mining Company was merged with the Iron Cliffs Company of Marquette, Michigan, which owned a large area of neighbouring acreage in Marquette County, and thereafter the new corporation was called the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company. It has operated a great many vessels in its Cleveland-Cliffs Steamship Company, and at least fifteen other lake shipping firms either have been subsidiaries of Cleveland-Cliffs or have been major charterers of ships to the Cliffs fleet.

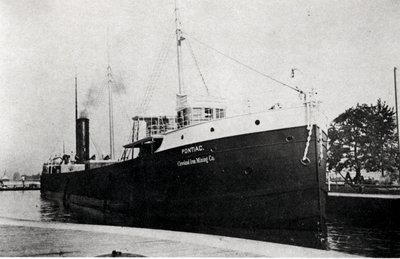

Extremely early photo shows PONTIAC, in the colours of the Cleveland Iron Mining Company, downbound in the Weitzel Lock at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan.

The nucleus of the fleet of the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company, when it was formed in 1890, were two near-sisterships named FRONTENAC and PONTIAC, which had been built in 1889 for the old Cleveland Iron Mining Company. The contract for their construction had been let to the Cleveland Shipbuilding Company, which built these steel-hulled bulk carriers as its Hulls 4 and 5, respectively .

PONTIAC, the vessel with which we are primarily concerned, was enrolled at Marquette as U.S.150476. She was 300.0 feet in length, 40.0 feet in width, and 24.8 feet in depth (although there is some difference in her depth as quoted in various years of the U.S. vessel register). PONTIAC was some thirty feet longer than FRONTENAC, and her tonnage was registered as 2298.36 Gross and 1788.45 Net. We know nothing about her engines or boilers, but the shipping registers recorded that her machinery was capable of developing an Indicated Horsepower of 1,220.

William G. Mather was vice-president of the Cleveland Iron Mining Company at the time that FRONTENAC and PONTIAC were built, and it was through his influence that the company switched from wooden hulls to more modern steel-hulled vessels. All of the previous boats owned or chartered by the fleet had been built of wood, but Mather realized that only through the construction of steel hulls could the company keep pace with contemporary developments.

A number of contracts were let at about the same time for the construction of steel-hulled ships for various operators, but the Cleveland Iron Mining Company was the very first iron mining concern to build steel vessels for the transportation of its own product to the mills. And in the building of FRONTENAC and PONTIAC, the company gained two very handsome steamers.

PONTIAC was a graceful vessel indeed, with a sweeping sheer to her decks and a marked rake to her stack and three masts. She had a raised forecastle which was topped by a slightly turtle-backed deck designed to shed any water that she might take over the bow. The bridge structure was set back off the forecastle, with a large square texas cabin on the spar deck, and the pilothouse raised a deck and a half above and situated just forward of a small cabin in which were provided the master's quarters. An open navigation bridge was located on the monkey's island above the pilothouse and flying bridgewings ran out to the sides of the ship from the roof of the master's cabin. The foremast rose out of the spar deck just abaft the forward cabin.

The spar deck itself was, in the fashion of the day, enclosed all around by a closed rail, a feature which tended to accentuate the sheer of the deck. About half-way down the deck was located a small deckhouse, or "doghouse", in which was located additional crew accommodations, and it was out of this cabin that the mainmast rose.

The after cabin took up PONTIAC's entire fantail area, and was sheltered by the overhang of the boat deck. At its forward end was a slightly indented boilerhouse, out of which sprouted the steamer's tall and fairly heavy funnel, which was surmounted by a double-roll cowl. The mizzen mast rose out of the cabin just abaft the stack, and the lifeboats were carried on the boat deck, one slung on either side of the funnel.

PONTIAC's hull was painted black, while the forecastle was white. Her name, together with the legend "Cleveland Iron Mining Co.", appeared in white on her bows. The cabins were a dark colour, while the fancy trim on them was white. We are not certain whether the cabins at this stage were the same green that is now a Cleveland-Cliffs trademark, or whether, perchance, they may have been red or a reddish-brown colour. In any event, the stack was completely black.

PONTIAC appears to have been a great success and her owners were very proud of the steamer and her cargo capacity, which was much larger than that of the small wooden vessels that she had replaced. With the formation of the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Company in 1890, there were certain changes in PONTIAC's appearance, but the absence of colour renditions of the vessel during those years makes it difficult to describe her livery with any accuracy. Suffice it to say that the pilothouse became white. There is some suggestion that Cliffs vessels wore red hulls for the first few years of the new company's existence.

Things went well for PONTIAC until Tuesday, July 14, 1891. On that morning, PONTIAC was downbound with a cargo of iron ore, while the Canadian Pacific Railway's passenger and package freight steamer ATHABASCA was upbound from Owen Sound to Sault Ste. Marie and the Canadian Lakehead. The Little Rapids Cut channel of the St. Mary's River had not yet been dredged out, and all traffic proceeded through the Lake George Channel to the east of Sugar Island. On that particular morning, ATHABASCA and PONTIAC met in the Wilson's Bend area of the Sugar Island Channel of Little Lake George, where the navigable pass was relatively narrow.

It seems, however, that all was not sweetness and light between Capt. James F. Foote of ATHABASCA and Capt. Lowes of PONTIAC. Capt. Foote took exception to the fact that PONTIAC, in his opinion, refused to give any ground in a passing and crowded the proud passenger steamer to the extreme edge of the channel whenever the two boats met. On this particular occasion, things were not played according to the usual script.

Capt. Foote held his position in the channel, as did Capt. Lowe, and the ATHABASCA struck PONTIAC a dead bow-on blow, opening such a gaping hole in the freighter that she sank immediately on the spot. There was little damage to ATHABASCA, but when she finally made her way to the Soo, the entire foredeck from PONTIAC was balanced across her bows, the whole turtle-back structure having been torn loose in the impact. Upon the insistence of the insurers, the Canadian Pacific Railway was forced to dismiss Capt. Foote after the accident but, in view of his actions in upholding the honour of the ATHABASCA and the pride of her owners, he retained the good will of the railway and was awarded a handsome pension as compensation for the consequences of his actions.

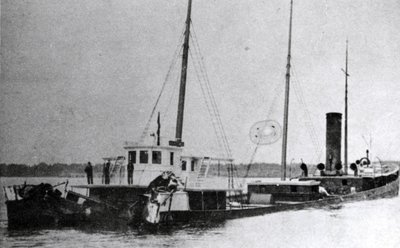

PONTIAC looked like this after her collision with ATHABASCA in the Little Lake George Channel of the St. Mary's River, July 14, 1891. Note the fact that her entire foredeck is missing.

PONTIAC, meanwhile, lay on the bottom of Lake George, submerged up to her spar deck, and with her bow completely opened up as if she had been attacked in some manner by a can-opener. Photos of her in this position show her officers standing on the bridge deck, looking down in disbelief at the shattered bow of the ship. It was as if they could not believe that the superiority of the two-year-old steamer could possibly be challenged by any vessel, even by one of the crack passenger steamers of the premier Canadian upper lake line. In any event, PONTIAC's bow was soon patched, and the freighter raised and hauled off to drydock for repairs. She re-entered service later the same year with her forecastle, if not her pride, restored to its pre-collision state. We have no knowledge as to whether Capt. Lowe suffered any disciplinary measures as a result of his role in the collision.

PONTIAC remained in service for Cleveland-Cliffs for another decade and a half after the ATHABASCA incident, and she served her owners well during this period. In due course of time, her cabins became all green, with white trim, while her stack remained black but took on a large white letter 'C'. The letter shortly became red, and the 'C' still graces Cliffs stacks to this day, although the colour now has been changed to a lighter, phosphorescent tone of red. PONTIAC's hull was black and her forecastle white. Under her name on her bows was the legend "The Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Co." in white letters.

By 1916, when the next date-identifiable photo of PONTIAC that we have was taken, the ship had changed somewhat. She still retained her old lines and colours, but her stack had lost its double-roll cowl and now bore nothing more than a simple rim around its top. All three of PONTIAC's original masts had been removed, and in the case of the fore and main this was undoubtedly done to clear the way for the ore-unloading rigs so that they had unobstructed access to the hatches. A new foremast rose from the texas roof, while a new main was stepped well abaft the stack. Both new masts were very thin steel poles, and they were bent so that any vestige of rake was destroyed; their upper extremities almost seemed to lean forward.

As well, the deckhouse was removed from the mid-ship area of the spar deck, no doubt also in an effort to clear the deck for cargo handling. The crew that had been housed within were found accommodation elsewhere, and where the cabin had been a large deck winch was fitted, with access to the sides of the ship for the mooring lines being provided via large fairleads set into the closed bulwarks.

But the days of PONTIAC's value to the Cleveland-Cliffs organization were drawing to a close. A large number of modern steel bulk carriers had been constructed for the fleet and its various affiliates in the early years of the new century, and FRONTENAC and PONTIAC found themselves completely outclassed. They lasted with Cliffs into 1917, undoubtedly being retained that long only because of the demand for tonnage that was created by the war.

Early in 1917, Cliffs sold FRONTENAC to the Mentor Transit Company of Cleveland, which was managed by Capt. Wesley Cunningham Richardson, who built up a large fleet of vessels to carry ore for Oglebay Norton and Company, and who is credited with originating the fleet that later became the Columbia Steamship Company and today is known as the Columbia Transportation Division. PONTIAC also was sold, being transferred on February 1, 1917, to the Crescent Transit Company of New York, which was managed by Richardson.

Although FRONTENAC retained her old name under Richardson management, PONTIAC was immediately renamed. She was rechristened (b) GOUDREAU (I). this name being chosen to honour the Goudreau District of Northern Ontario, an area north of Sault Ste. Marie which was a major producer of gold and pyrites. Pyrites were to be GOUDREAU's cargo on many occasions during the 1917 season. In Richardson service, GOUDREAU was painted black with white forecastle and cabins. Her stack was all black.

With the need for tonnage on salt water increasing in the final stages of World War One, however, many of the smaller upper lakers were being cut in two and sent down through the canals, to be joined again on the St. Lawrence and steamed out to the coast. Both FRONTENAC and GOUDREAU, which were not very much larger than canal size, were scheduled to go to the coast in 1918, and FRONTENAC actually made the trip. GOUDREAU, however, was to meet her fate on the Great Lakes before the 1917 navigation season came to an end.

A nasty late-autumn gale swept over the lakes on Thursday and Friday, November 22 and 23. 1917, making navigation treacherous on all of the lakes. Interestingly enough, however, the storm claimed only one ship as a victim, and that was GOUDREAU. She was downbound in upper Lake Huron with a cargo of pyrites when the storm caught her. With the heavy seas sweeping down on her stern in the northwesterly gale, GOUDREAU lost her rudder, and was then at the complete mercy of the elements. The helpless steamer was driven before the gale and drifted across the lake toward the Canadian shore. On November 23rd, she finally struck the lee shore on Southeast Shoal, some five miles southwest of Lyal Island. The island itself is located just off Stokes Bay and about half-way up the Lake Huron shore of the Saugeen Peninsula, or put another way, about mid-point between Southampton and Tobermory.

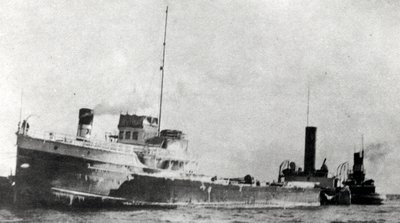

In her position on the lee shore, GOUDREAU was fully exposed to the fury of the gale, and she pounded badly on the shoal. Eventually she broke in two, the hull being severed just forward of the after cabin. The bow section was completely separated and swung away approximately 45 degrees to starboard. The Reid Wrecking Company was summoned to the aid of the ice-encrusted GOUDREAU, and the wrecking crews worked on the vessel for about a week. Finally, however, unfavourable weather again set in and the Reid tugs were forced to leave the wreck. GOUDREAU was abandoned to the underwriters on December 1st, and recurring storms during the late autumn and winter pounded the wreck until the ship became a complete loss. A contemporary report stated that only her machinery was considered to be recoverable, but we have no record of even that much of her being reclaimed from the clutches of Lake Huron and Southeast Shoal.

The completely severed bow and stern sections of GOUDREAU lie on the shoal off Lyal Island, Lake Huron, after the stranding of November 23, 1917.

And so, the autumn gales of Lake Huron accomplished what Capt. Foote and the ATHABASCA had failed to do twenty-six years earlier, and the career of PONTIAC/GOUDREAU came to an end after twenty-nine years of service. One might almost think that GOUDREAU had taken matters into her own hands in order to escape from being cut apart and sent off to the east coast, where she would have had to endure the rigours of service on the open ocean, a trade for which she had never been designed or constructed.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.