Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| G. A. Tomlinson Souvenirs | |

| 6. Ship of the Month No. 92 JOHN S. THOM | |

| The Shipbuilders | |

| Additional Marine News | |

| Table of Illustrations |

Back in December of 1972, we featured in these pages the two-stacked, wooden-hulled package freight steamers OATLAND and JOYLAND, two veterans which began life in 1884 as WM. A. HASKELL and WM. J. AVERELL (sometimes spelled AVERILL) respectively. They both lived to a ripe old age, although a third sister, WALTER L. FROST, did not. Readers who recall the story of these vessels will remember that they were followed from their builder's yard a few years later by five more boats of somewhat similar design, this latter group also being built to the order of the Central of Vermont interests. It is one of these later steamers that we have chosen for our present feature, for we have never before dealt in any detail with any of the five.

In the years before the turn of the century, and even for a short while afterwards, many of the railroads in the northern United States maintained not only thriving rail operations but also connecting steamboat services on the Great Lakes. One such company was the Ogdensburg and Lake Champlain Railroad, later known as the Central of Vermont and still later as the Rutland Railroad. It was in 1883 that the railroad formed a lake shipping subsidiary whose purpose it was to transport package freight by water between Ogdensburg, N.Y., and Chicago. The new company, first known as the Ogdensburg Transit Company and later as the Rutland Transit Company, appears to have taken over the trade of the old Northern Transportation Company (or Northern Transit Company, as it had become known) which had begun the liquidation of its outdated fleet in 1882.

The AVERELL, HASKELL and FROST were the first ships built for the Ogdensburg Transit Company but, six years after their construction, the line felt the need for additional tonnage to assist them and to replace several chartered vessels. Contracts for five new steamers were let to the Detroit Dry Dock Company and all of them were turned out by the builder's yard at Detroit during the 1890 season. They were christened GOV. SMITH (Hull 97), JAMES R. LANGDON (Hull 98), A. McVITTIE (Hull 99), F. H. PRINCE (Hull 102) and HENRY R. JAMES (Hull 104).

The last of these vessels, HENRY R. JAMES, was enrolled as U.S.96055, her home port being Ogdensburg. A 'tween-deck package freighter with a wooden hull, she measured 240.0 feet in length (253.4 feet overall), 42.0 feet in the beam and 23.4 feet in depth, these dimensions producing registered tonnages of 2048.01 Gross and 1552.71 Net. The JAMES and all her sisters (for they were nearly identical) were powered by similar compound engines built for them, as were the boilers, by the Dry Dock Engine Works, a firm affiliated with the shipbuilder. JAMES was fitted with engine number 163 which had cylinders of 28 and 52 inches and a stroke of 40 inches. Steam was supplied by two cylindrical Scotch marine boilers, 12 feet by 10, numbered 77 and 78 by their makers; coal-fired, they produced a working pressure of 120 p.s.i.

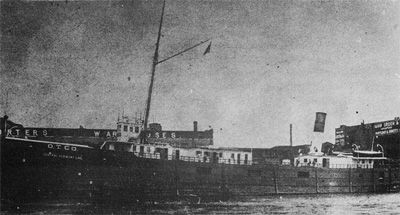

This is HENRY R. JAMES as she appeared from 1896 until shortly after 1900. Photo from the Bascom collection.

It is rather difficult to understand why the railroad ordered five wooden-hulled package freighters as late as 1890. By this time, iron-hulled steamers had been ordered by several lines, perhaps the most famous of these being the beautiful HUDSON and HARLEM, built in 1887 and 1888 by the Wyandotte yard of the Detroit Dry Dock Company for the Western Transit Company, the marine affiliate of the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. Undoubtedly, the Central of Vermont management was influenced by the success which had followed the commissioning of its own earlier trio of boats, but perhaps they were also a bit shy to leave aside so many years of tradition in shipbuilding and to take a chance on a form of construction upon which so many old-line shipping men looked somewhat askance. Perhaps, had the steamers been given iron hulls, they might have served the railroad and its successors for more than the twenty years that they ran for their original owner.

HENRY R. JAMES and her sisters were somewhat more modern than the earlier trio of steamers, but they were still typical of the wooden package freighters of the era. High-sided and bluff-bowed, they were equipped with large cargo ports on each side to facilitate the loading and unloading of freight. Two large cabins were mounted on the spar deck, or what might better be called the "upper deck", these providing most of the accommodation for the officers and crew. The texas, as the largest and farthest forward of these cabins might loosely be termed, was topped with a handsome square pilothouse, complete with three large sectioned windows across its front. Navigation was normally done from the open bridge located on the monkey's island, protection from the elements being provided by a canvas "dodger" or weathercloth, and by an awning overhead.

The after cabin was a smaller structure, from which sprouted a tall and fairly heavy smokestack, well raked to match the very tall mast which rose immediately abaft the pilothouse. The mast was fitted with a gaff, but there is no evidence that a boom was ever carried or that any of the boats were ever equipped to carry auxiliary sail. As built, all five vessels had but one mast but, as the years passed, they were given an interesting assortment of rather scrawny mainmasts. The first of these seems to have been located just abaft the "texas" cabin but, in later years, the main was relocated immediately forward of the stack. The five ships seem to have had their mainmasts set in slightly different locations. The hulls were given a sweeping sheer and the uplift of the bows was accentuated by the appearance of the anchor stocks which protruded from the closed bulwarks on the flush forecastle. The anchors themselves rested right on the open foredeck.

The Ogdensburg Transit Company's steamers seem to have carried a variety of colour schemes over the years. When built, JAMES and her sisters had black hulls and grey boot-tops, only the upper edge of the forecastle rail being white. The cabins were dark in colour, probably a shade of brown, and the stacks were white with a black smokeband which extended fully half way down the length of the funnel. The legends "O.T.Co." and "Central Vermont Line" appeared in white on the bows, the former on the rail and the latter beneath on the planked-in side of the 'tween deck. During 1896, the cabins began to be repainted white, although the shutters gracing the cabin windows remained a dark colour, probably brown or perhaps green. The rest of the colours remained the same until, shortly after the turn of the century and definitely prior to 1903, "the hulls were repainted white. The boot-top remained grey but the "O.T.Co." on the rail was changed to a black "R.T.Co." (indicating the advent of the Rutland years) and "Central Vermont Line" gave way to the black legend "Ogdensburg Line".

HENRY R. JAMES and her sisters, together with the earlier trio, led a gruelling life in the service of the Ogdensburg and Rutland Transit Companies. The line had the longest route of any of the American lake package freight services, for not only was it the only one to operate down onto Lake Ontario (most had their eastern terminus on Lake Erie), but the steamers had to push on down the St. Lawrence River as far as their home port of Ogdensburg. The route was particularly hard on the wooden ships since each round trip necessitated two tedious passages through the 27 small locks of the old Welland Canal. Eastbound, the ships could be found with their holds full of grain, but their westbound cargoes consisted of the usual general cargo plus large quantities of granite which was unloaded at Chicago for the building trades.

The five sisterships carried on with their usual route between Ogdensburg and Chicago until the latter half of the first decade of the new century. On August 19, 1906, GOV. SMITH was lost by collision with URANUS on Lake Michigan and, in the same year, the line commissioned its first steel-hulled canal-size package freighters, OGDENSBURG and RUTLAND, which were built at Cleveland by the American Shipbuilding Company. More steel canallers followed, BENNINGTON (I) and BURLINGTON (I) in 1908 from the Great Lakes Engineering Works at Ecorse, and ARLINGTON (I) and BRANDON in 1910 from the Wyandotte yard of the Detroit Shipbuilding Company, the successor to the Detroit Dry Dock Company.

As the newer steamers appeared, the older vessels were gradually relegated to standby status and it is fairly certain that they had been withdrawn from regular operation by 1910, although they undoubtedly saw fill-in service as necessary. HENRY R. JAMES, JAMES R. LANGDON and A. McVITTIE were sold for other service in 1910, while F. H. PRINCE was the victim of a fire which occurred on August 14, 1911. With all five of the newer ships having left the fleet, the only remainders of the wooden era still in the company's colours were HASKELL and AVERELL, their sister WALTER L. FROST having stranded to a total loss on South Manitou Island, Lake Michigan, on November 4, 1903. HASKELL and AVERELL remained with the Rutland until the Panama Canal Act forced the railroads to divest themselves of their lake shipping affiliates at the close of the 1915 season. The fact that they lasted longer than their newer, single-stacked counterparts was probably due to nothing more interesting than the fact that they were six years older and, as such, less likely to attract buyers.

HENRY R. JAMES and JAMES R. LANGDON both were acquired in 1910 by the same purchaser, namely the Quebec and Levis Ferry Company Ltd. of Quebec City. It was intended that the two steamers carry the cars of the Grand Trunk Railroad across the St. Lawrence River, railway access to Quebec City having been delayed by the 1907 collapse of the uncompleted Quebec Bridge. The company's ferry route was from a landing just above the Davie Shipyard's patent slip at Levis to Atkinson's Wharf which was located near the Quebec City customs house.

The JAMES was reregistered at Quebec as C.126388 and was renamed (b) JOHN S. THOM in honour of the gentleman who, at the time of her purchase, was the president of the ferry company. Her sister became (b) CHARLES H. SHAW and was named for the company's vice-president. Both steamers were taken in hand by Davie Shipyards and were cut down for their new service as carferries, their 'tween-decks being removed and their superstructures aft of the forecastle cut down to the main deck except for a high bulwark which was left for protection. Tracks were then laid athwartship on the main deck and these provided space for some eight or ten standard freight cars. After this operation was performed on the THOM, she was a very strange-looking vessel indeed. Her pilothouse, once again painted a brown colour, perched atop a shortened texas which was moved forward on the very high forecastle. Her deck was, of course, very low and, because her side planking had been cut away right aft to the fantail, she was left with a peculiar double-deck after cabin, from the upper level of which sprouted her stack. This cabin looked all the more odd in that it was not situated all the way aft but rather closer to the midships section of the hull. The hull itself was black at this stage and the stack was black with a wide silver band. After the rebuild, JOHN S. THOM's depth was reduced to 14.9 feet and her tonnage to 1440 Gross and 911 Net.

JOHN S. THOM, surrounded by Playfair canallers and with FRANK B. BAIRD at far left, awaits upbound passage at Port Dalhousie c. 1924. Photo by Rowley Murphy from the Bascom collection.

JOHN S. THOM and her sister shuttled back and forth across the St. Lawrence from 1910 until a new railway bridge spanning the river was opened in 1916. One would have thought that this event would have finished off the THOM and the SHAW for good, but such was not the case. The Quebec and Levis Ferry Company decided to place them both in the coal and pulpwood trades on the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. Considering their age and condition, this decision would have been surprising had it not been for the great demand for tonnage which had been created by the First World War; many of the more modern canallers had been requisitioned for salt water service and almost any bottom that would float was pressed into service as replacement tonnage.

During the summer of 1917, however, the THOM was involved in a stranding which very nearly proved to be her undoing. Had it not been for the war, she would probably never have been salvaged from her resting place on the rocky shoal protruding into Lake Ontario beneath the Devil's Nose, that high and bold promontory on the south shore of the lake, some 22 miles west of Charlotte. The Devil's Nose had proven fatal to many lake vessels over the years, particularly during the era of sailing ships which were easily trapped on the lee shore in heavy weather. But salvaged the THOM was and, for the full story of the accident and the refloating of the steamer, we can do no better than to quote the words of her master, Captain William J. Stitt, as contained in C.H.J. Snider's "Schooner Days", Number CCCXXII, which appeared in the Evening Telegram, Toronto, on Saturday, December 11, 1937.

JOHN S. THOM needed a lot of work after her escapade on the Devil's Nose and she remained in the Davie shipyard at Levis over the winter of 1917-18. Much money was expended on her refurbishing but, rather than putting the THOM back in lake service in the spring of 1918, the Quebec and Levis Ferry Company Ltd. sold her for the sum of $160,000 (quite a price for those days) to New York interests. For seven years, JOHN S. THOM operated on salt water but it does not seem that she was placed in United States registry, as she does not appear in the "Merchant Vessels" listings. What she did on salt water, we do not know, but we find it hard to imagine that the THOM was particularly suited for operation on open waters along the coast.

Perhaps even more surprising than the THOM's continued operation after the cessation of the Quebec railferry service or her escape from the Devil's clutches was her return, at the grand old age of 35 years, to the ownership of the Quebec and Levis Ferry Company Ltd. which reacquired her at a cost of $70,000 during 1925 and brought her back to the lakes. Back in her old colours again, and looking just as she had before her venture onto salt water, JOHN S. THOM went back into the coal and pulpwood trades, staying mainly on the St. Lawrence River and Lakes Erie and Ontario. Seldom did she stray onto the upper lakes, for she was hardly in any condition to withstand the rigours of heavy weather.

JOHN S. THOM plodded along for a few more years in the service of the Quebec and Levis Ferry Company, but she was nearing the end of her days and, as might be expected of a wooden hull nearing the end of its fourth decade of service, more and more work was required to keep her in operation. The onset of the Great Depression spelled the end for her and, during 1930, she was laid away to rest in the St. Charles River at Quebec City. There she mouldered away in the boneyard and it seems likely that her last remains were dismantled during the late 1930s. Even so, the THOM lasted longer than any of her sisters. A. McVITTIE survived, cut down to a bulk carrier and later acquired by the Montreal Transportation Company Ltd., until she sank in Kingston Harbour during November of 1919. Her hull was finally dismantled in 1925. CHARLES H. SHAW, the THOM's companion in the ferry service and coal and pulpwood trades for eight years, ran until about 1920, at which time she also was laid up in the St. Charles River. Unlike JOHN S. THOM, she never went to salt water and she was eventually dismantled about 1927.

JOHN S. THOM, although she was a good-looking vessel back in her package freight days for the Central of Vermont, was never a handsome boat after being cut down for the ferry service. In fact, she was downright homely and one of the strangest ships ever to serve on the lower lakes. She did, however, fulfill a useful purpose and merits our acknowledgement, even after the passage of so many years since she last turned a wheel.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.