Table of Contents

To those who may not have known them well, the steam canallers of the first six decades of this century must seem pretty much alike, those dumpy, bluff-bowed little steamers that shuttled back and forth carrying their cargoes through the diminutive locks of the old canals. To the trained eye, however, they were all different. Not only that, but they fell into distinct classes according to the year of build and the yard from which they came. Indeed, those who got to know the canallers well could easily identify the builder by a quick look at the lines of a boat's hull (or lack of them), the configuration of her cabins and the cut of her counter.

This time around, we'll take a look at a group of three canallers which made their appearance on the lakes not long after the turn of the century and marked an important step in the transition from wooden hulls to steel along the canals. One of the ships lasted but seven seasons on the lakes, another served for just a decade, but the third traded up and down the lakes for 52 years, a life far longer than that of the average canaller.

Two of the most famous names in Canadian lake shipping history were those of Roy M. Wolvin of Winnipeg (and formerly of Duluth) and Captain J. W. Norcross of Port Colborne. The paths of these two eminent gentlemen crossed and in 1907 they together formed two companies for the purpose of engaging in lake transportation. One of the firms was the Mutual Steamship Company of Port Colborne, while the other was the Canadian Lake Transportation Company Ltd. of Toronto. It is with this latter firm that we shall now concern ourselves, although we shall hear again later of the Mutual Steamship Company.

The Canadian Lake Transportation Company Ltd., having been brought into being to operate ships, now needed to obtain ships which it could operate. The company, in its first year of existence, let contracts for the construction of three canal-sized steamers and, like many lake shippers of the day, went off-lakes to search for a shipbuilder. They chose the firm of A. McMillan and Sons Ltd. of Dumbarton, Scotland, and before long the keels were laid for their first three vessels.

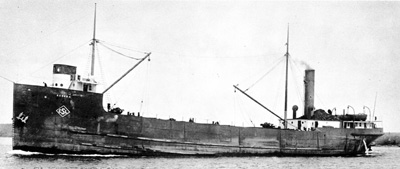

The first of the trio to be launched was REGINA which hit the water on September 3, 1907. She was named in honour of the capitol city of the province of Saskatchewan and she was given official number 124231. She was originally registered at Glasgow but it appears that she was later reregistered at Toronto. REGINA measured 249.9 feet in length, 42.6 feet in the beam and 20.5 feet in depth, her Gross Tonnage being listed as 1,957. We do not have confirmation of her Hull Number, but we have every reason to believe that she was McMillan's Hull 419.

REGINA was a single-screw vessel and was powered by engines and boilers made especially for her by Muir and Houston Ltd. Steam at 185 p.s.i. was supplied by two coal-fired, single-ended Scotch boilers measuring 12 feet by 10 feet 10 1/4 inches. Her direct-acting, surface-condensing, triple-expansion engine had cylinders of 17, 28 and 46 inches and a stroke of 33 inches, and developed an Indicated Horsepower of 650. The boilers also supplied steam for the circulating pump, auxiliary duplex feed pump, ballast pump, etc., as well as for her steering engine, a steam capstan mounted aft and two three-ton double-cylinder steam deck winches.

REGINA and her two sisters were designed and built as package freighters. Accordingly, she was fitted with 'tween decks and had three cargo ports on each side. Her two tall masts, the foremast just aft of the forecastle and the main just forward of the boilerhouse, were each fitted with a heavy cargo boom to assist in the loading and unloading of general cargo. She had six deck hatches.

The new steamer had a raised forecastle and flush quarterdeck. On the forecastle was located the texas cabin and a small, rounded chartroom. Above the latter was the pilothouse, a small, wooden structure with five windows across the front. Painted white (as were the rest of the cabins) up to just below the level of the windows, the upper portion of the pilothouse was varnished teak as were the doors, giving the ship's forward end a somewhat unusual appearance. The pilothouse was not equipped originally with a sunvisor. A large and substantial cabin was fitted aft with a recessed boilerhouse at its forward end. It was surmounted by an impressively tall funnel and just aft of the stack was the bunker hatch.

REGINA's hull was painted black and she was given a green boot-top and a white forecastle rail. The cabins were white and the funnel was all black. REGINA and her sisters, unlike most of the canallers, had a great sweeping sheer to their hulls. When light, they lifted their bows high but when loaded deeply they tended to ride with the stern lifting noticeably.

REGINA was duly completed by her builders and sailed in ballast for Canada, arriving at Montreal during October 1907. She was immediately put into the package freight service between Montreal and the Canadian Lakehead, operating in what was familiarly known as the "Canadian Lake Line". She did not have it when she first came out, but in later years she would carry this name in white on her bows.

Meanwhile, A. McMillan and Sons Ltd. had gone to work on the second of the ships and she was launched in early October 1907. She was the yard's Hull 420 and she was given official number 124235. The steamer was christened KENORA in honour of the town located in the Lake of the Woods area of Northwestern Ontario. The town's name itself had an interesting derivation, the first two letters being taken from the Territory of Keewatin, the middle two from Norman, another area settlement, and the last two from Rat Portage, the original name of the town.

Even though she carries C.S.L. colours, this 1915 Young photo shows KENORA much as she appeared when built.

KENORA was almost an exact sistership of REGINA and her basic hull measurements were the same. Her tonnages were a bit different, her Gross being listed as 1,955 and her Net as 1,275. Her machinery was the same as that fitted in her sister and was supplied by the same firm. KENORA was completed in early November and she sailed in ballast for Montreal. Upon her arrival, she loaded a cargo of sugar and on November 26, 1907 she sailed for Hamilton. Once the sugar had been unloaded at that port, she proceeded to Toronto where she was put into winter quarters. She entered regular service on the package freight route of the Canadian Lake Line in the spring of 1908.

The third boat in the series did not get across the Atlantic until the summer of 1908. Christened TAGONA, she was given official number 128188. We do not know her hull number. A bit different from REGINA and KENORA, she was 249.6 feet in length, 42.6 feet in width and 21.1 feet in depth, these measurements giving her tonnage of 2,004 Gross and 1,299 Net. As far as we know, she had exactly the same machinery. Her appearance was generally similar to that of her two sisters, but she had a rather larger pilothouse with seven windows across its front. The pilothouse was not varnished and was painted white but in typical fashion it did not have a sunvisor.

TAGONA arrived in Toronto for the first time on July 14th, 1908, her crossing of the Atlantic having been delayed by a minor grounding incident on the coast of Newfoundland. On her arrival, she joined REGINA and KENORA in normal lake service.

REGINA, KENORA and TAGONA were the only three package freighters built by McMillan's yard to their particular design. It should be noted, however, that there were several other canallers built by McMillan which were somewhat similar in appearance to our trio. GLENMOUNT (I) and STORMOUNT (I) were built in 1907 for the Montreal Transportation Company Ltd, while PRINCE RUPERT was completed in 1908 for the Kingston Shipping Company Ltd. and the C. A. JAQUES in 1909 for the Merchants Montreal Line. These four ships were, however, bulk carriers not package freighters.

For the first few years of their lives, our three steamers operated uneventfully. They were involved in no major accidents of any sort and plied their unglamourous trade up and down the St. Lawrence and Welland Canals, already looking very small on the upper lakes compared to the vessels then being built in shipyards there. But behind the scenes were happening events that were eventually to change the entire appearance of shipping on the Canadian side of the border and behind these machinations were none other than Roy Wolvin and Capt. Norcross, the principals of the Canadian Lake Transportation Company Ltd.

On May 2, 1910, Wolvin and Norcross merged their Mutual Steamship Company with the Merchants Steamship Company, Toronto, to form the Merchants Mutual Line Ltd. of Toronto. The principals of the new firm were D. B. Hanna, president; Z. A. Lash, vice-president; Sir Henry M. Pellatt, Frederick Nicholls, and W. H. Moore, directors. It so happened that these gentlemen, along with others, also controlled the Canadian Lake and Ocean Navigation Company Ltd. of Toronto.

During 1911, the Merchants Mutual Line Ltd. was merged with the Canadian Lake Transportation Company Ltd. to form the Canadian Interlake Line Ltd. This new concern had as its president M. J. Haney, as its managing director, Capt. J. W. Norcross, and as its operating superintendent Capt. H. W. Cowan. In 1912, the company was reorganized as the Canada Interlake Line Ltd. and its principals were: M. J. Haney, president; Roy M. Wolvin, vice-president; H. Munderloh, Montreal, E. H. Ambrose, Hamilton, J. F. M. Stewart, Toronto, T. Bradshaw, Toronto, and Capt. J. W. Norcross, Toronto, directors. None other than Capt. Norcross served as managing director. R. O. MacKay and A. B. MacKay of Hamilton had been the operators of both Merchants Mutual and Canadian Lake and Ocean but they withdrew from the scene when the Norcross - Wolvin interests took over in 1911.

The final step in the master plan took place on June 11, 1913 when Wolvin and Norcross consolidated the various lines over which they had gained control and, with the help of certain other interests, formed what was originally called the Canada Transportation Company Ltd., the name shortly being changed to Canada Steamship Lines Ltd., Montreal. The Canada Interlake Line Ltd. was one of the concerns merged into the new company and as a result, REGINA, TAGONA and KENORA became units of the C.S.L. fleet. Despite the merger, however, the Canada Interlake boats continued to operate under the name of the Merchants Mutual Line, the familiar name being kept for a few years, presumably in an effort to overcome opposition to the new order of things.

It took a bit of time for the many ships in the giant C.S.L. fleet to be assimilated into the new line's operations. KENORA and TAGONA would eventually be given the company's new colours but for 1913 at least, things continued pretty much as they had been. By this time, the appearance of REGINA had been modernized a bit by the addition of a sunvisor to her pilothouse and the painting of that cabin white. Even so, she still frequently boasted a large, striped awning stretched out over the forecastle in the old style.

But REGINA was to be the first of our three sisters to drop out of sight and she did so in a terrifying manner that managed to grab headlines in almost every paper in Canada and the northern United States. November 1913 is a month that will never be forgotten by lake sailors or historians, for never in the history of the lakes has there ever been another month in which so many ships and lives have been lost on Great Lakes waters. REGINA was one.

The days around what is now known as Remembrance or Armistice Day, November 11th, have for many years been known for the violent weather conditions that seem likely to occur in the Great Lakes area at that time of year. But in November 1913, there developed over the lakes a storm situation such as has never been seen before or since. The storm, consisting of unusually high and unstable wind conditions, below-normal temperatures and heavy snowfall, lashed the lakes for three days but the worst of the fury struck the lower Lake Huron area in the late afternoon and evening hours of Sunday, November 9th.

Earlier that day, REGINA had passed up the St. Clair River and out through the Huron Cut into Lake Huron. As she passed Port Huron, an employee of the local vessel reporting agency remarked that REGINA seemed to be carrying a particularly heavy deckload of sewer and gas piping. She moved out into the lake in what was probably considered to be nothing more than typically bad fall weather. Thanks to the undeveloped state of weather forecasting at that time and to the fact that this storm moved in ways that none reported had ever done before, the masters of vessels on lower Lake Huron that day had no idea of what surprises the lake had in store for them. Had Capt. E. H. McConkey of the REGINA known, he would have held his ship within the safety of the St. Clair River.

A vessel which preceeded REGINA out into the lake, the bulk carrier H. B. HAWGOOD in command of Capt. A. C. May, was the last ship whose men ever saw REGINA and lived to tell about it. The HAWGOOD had been upbound but in the face of the heavy gale, Capt. May decided to turn and run back down the lake (the ship eventually grounded just above Point Edward). Shortly after making his turn, he saw REGINA still heading uplake. At that point, she was about fifteen miles south of Harbor Beach, Michigan. Not long before, the HAWGOOD had also passed the steamer CHARLES S. PRICE and not long after she would meet the ISAAC M. SCOTT, both of these vessels also being lost in the storm. The PRICE was found a few days later floating upside down about eleven miles above the Huron Cut and the SCOTT was not seen again until the summer of 1976 when her wreck was located off Thunder Bay Island. The poor little REGINA hasn't been seen again to this day, although for a while the overturned hull of the PRICE was thought to be that of REGINA.

The REGINA would have gone down in the books as just another of the ships that disappeared in the Great Storm of 1913 were it not for some unusual discoveries made along the beach on the Canadian shore of the lake near Goderich where many of the men lost with their ships in the storm eventually came ashore. One of them was John Groundwater, chief engineer of the CHARLES S. PRICE. The problem was that he was wearing a REGINA lifebelt when found and so also were several other men from the PRICE whose bodies found their way onto the beach. This led many observers to believe that the two ships had collided in the storm and that in the confusion the men might have jumped from one ship to the other. Unfortunately, the hull of the PRICE sank before it could be completely examined by divers, but as of today there is still no confirmation that the PRICE and REGINA came together in any way on the lake that day over sixty-three years ago. The end of REGINA may never be known and there is little point in speculating as we will never know the conditions that faced her in the final hours of her existence.

KENORA and TAGONA, by now units of the largest Canadian fleet ever to sail the lakes, carried on without their lost sister and it is likely that the fleet did not suffer much as a result of her loss, having as it did many more units than it could possibly use economically. They carried on through 1914 and into 1915 at which time both ships were requisitioned by the Canadian government for salt water service during the First World War. As of August 5th, 1915, KENORA and TAGONA, together with many other canallers, were operating in deep-sea service and although many of them returned to the lakes during the winter of 1915-16, KENORA and TAGONA did not do so.

Not much can be discovered at this late date concerning the wartime exploits of our two steamers. Quite naturally, the comings and goings of the extremely vulnerable little canallers were not made widely known. The Dominion Wreck Commissioner's reports do, however, bear mention of each ship. KENORA is known to have gone aground off Flat Point, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, on August 2nd, 1915 while on passage from Montreal to Sydney in command of Capt. Burgess. It is entirely possible that this might have been her delivery voyage to the east coast. TAGONA got into trouble, but somewhat farther afield, when on November 1st, 1916 she suffered heavy weather damage off Scarweather Lightship whilst en route from Glasgow to Dunkirk. She was under the command of Capt. John Manuel at the time.

As far as we know, KENORA suffered no further ill effects from her enforced stay on salt water and she survived to sail the lakes once again. TAGONA almost made it back too, but not quite. With only a few months of hostilities remaining, she fell victim to enemy action. It was on May 16, 1918 that she was without warning torpedoed by a German submarine whilst in a position about five miles west-southwest of Trevose Head, England. She sank quickly and eight lives were lost when she went down.

And so, when hostilities ended, KENORA was the only one of the original three sisters that was still operating. She ran another year or so on salt water and then was brought back to the lakes about 1920 as C.S.L. attempted to get its lake operations back in order after having lost so many of its canallers during the war years, some the victims of enemy action and others having fallen prey to the heavy weather conditions for which they had never been designed.

But when KENORA came back to the lakes, she looked very much different from the ship she had been when she left in 1915. While she was on salt water, her bridge structure had been moved back off the forecastle to a less exposed location midway between the first and second sideports. It appears as if the original texas was moved down the deck (although it might have been a new deckhouse) and set between two new closed bulwarks. The old chartroom was discarded but the old pilothouse was set directly atop the texas and an open bridge was constructed atop the pilothouse. In addition, KENORA had gained a third mast. A stubby, heavy-set affair, it was really nothing more than a glorified kingpost and was set midway between the bridge and the boilerhouse, a cargo boom being slung forward from the new mast. The only other change was the addition of two heavy braces from the taffrail to the underside of the boat deck overhang aft. In latter years these braces seemed to serve no useful purpose but during the war years the empty space aft on the boat deck had been used as a gun placement and the supports had been installed to carry the weight of the ship's armament.

KENORA operated without major change during the twenties and thirties, although she was given an enclosed upper pilothouse, probably not long after her return to fresh water. KENORA, being a package freighter, was able to keep fairly active during the years of the Great Depression unlike the bulk carriers of the C.S.L. fleet, most of which spent considerable time in idleness. Then came the years of the Second World War and with them an increased demand for the services of the canal package freighters. KENORA had long since been surpassed in efficiency by new canal steamers but her carrying capacity was needed and about 1940 she was given a complete modernization.

This is the KENORA as she looked in the late thirties, caught in the Detroit River by the camera of Capt. William J. Taylor.

The steamer's mid-deck bridge was scrapped altogether and a brand new texas and pilothouse were constructed on the forecastle. Both cabins were much larger and more commodious than their predecessors and were relatively similar in appearance to the forward cabins given the newer package freighters of the fleet when built. The pilothouse had a handsome panel of five windows set in varnished frames and it's "ears" were a pair of rather noticeable door shelters. The bridge wings were given closed rails and looked most substantial even though they were enclosed only by plywood. The removal of the bridge from the shelter deck opened up more cargo-handling space and a cargo elevator was installed where the old bridge had been. The kingpost and its boom were removed and the mainmast moved forward, the latter now sporting two booms.

KENORA operated through the forties and fifties but as time went on she was frequently relegated to the status of spare boat, as were a number of the other older C.S.L. package freight canallers. Then, as the opening of the. St. Lawrence Seaway approached, it became evident that the handwriting was on the wall for the canallers. In 1957. the company dropped CANADIAN as well as the four smaller "City" class express steamers, CITY OF HAMILTON, CITY OF KINGSTON, CITY OF MONTREAL and CITY OF TORONTO, and in 1958 the veteran EDMONTON was retired. The year 1959 saw the opening of the Seaway and with it came the last gasp of the older package freighters. KENORA, BEAVERTON and CALGARIAN were all used strictly as spare boats, running off and on as needed. But none of them would finish out the year, nor would they ever operate again.

The aging KENORA, by now 52 years old, spent the latter part of the 1959 season laid up at Windsor, her services no longer needed. Canada Steamship Lines was beginning to weed the laid-up units from its fleet as it was obvious that they would never again be operated. One of the steamers sold was KENORA which in late autumn was purchased by the Steel Company of Canada Ltd. for scrapping at Hamilton. In due course, the McQueen tugs ATOMIC and PATRICIA McQUEEN came for the old girl and towed her from her lay-up berth, down the Detroit River, across Lake Erie and into the Welland Canal. It was a cold, blustery and snowy Sunday, November 29, 1959 on which the two tugs hauled their charge out through the piers at Port Weller and turned in the direction of Hamilton.

KENORA looked like this as she neared the end of her career. Photo by J. H. Bascom shows her approaching the Humberstone bunkers dock on May 31, 1958.

KENORA was cut up for scrap during the early months of 1960 and BEAVERTON and CALGARIAN followed her. CANADIAN had preceded her into the oblivion brought by the wreckers' torches. With the demise of KENORA, there disappeared from the scene not only the last of our famous trio of steamers but also the last of the canallers built in the early years of the century by A. McMillan and Sons Ltd. at Dumbarton, Scotland.

(Ed. Note: Try as we might, we have been unable to find out how TAGONA came by her name. We had thought that she was named for a town in western Canada, but we have not been able to locate any place by that name either on current maps or in older gazeteers. Can anyone help?)

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.