Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| Our Goof... | |

| Ship of the Month No. 165 Caribou | |

| The Smith's Dock Canallers Revisited | |

| Table of Illustrations |

Although there are occasions when we go through considerable effort in attempting to select a suitable ship to feature in these pages, we are seldom more pleased than when we can put together an article on a ship that has been requested by one or more of our members (and we always are glad to receive suggestions). However, in the nineteen years during which Ye Ed. has been at the helm (typewriter) of "Scanner", we have had more requests to feature the little Georgian Bay and North Channel steamer CARIBOU than any other vessel.

We have delayed doing a feature about CARIBOU because we really did not feel ourselves qualified to write about a ship that had become such an institution in her own local area. We were aware that many other people knew a lot more about the comings and goings of CARIBOU than did we, and we were hoping that we might be able to tap into that knowledge to produce a definitive history of the popular steamer which was so much of a lifeline to the residents of the areas that she served. One by one, however, the folk who knew CARIBOU in her early years have been passing from the scene and we finally decided that if ever we were going to write about her, we had better do so soon.

So here, at last, is the story of CARIBOU. We could think of no better time to feature her than in our twentieth anniversary issue.

It was in 1901 that the Dominion Fish Company Ltd. was formed as a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Booth Fisheries Corp., Chicago. Originally, the Canadian firm operated out of Sault Ste. Marie and also Goderich, but later its head office was moved to Owen Sound, Ontario. (At one time, around the First World War, the company's address was even shown in the Dominion register as Winnipeg, Manitoba.) The purpose of forming the Canadian subsidiary was to access Canadian fisheries as sources of fish for shipment to the U.S., and to do so it was necessary to operate ships that would go around to the small ports of northern Lake Huron to gather up the fish that was caught in those areas. At the same time, of course, other freight could be carried to and from the isolated communities, and passengers could also be transported.

In 1903, the Dominion Fish Company Ltd. was operating two small wooden-hulled steamers from Owen Sound to Sault Ste. Marie and Michipicoten, with stops at the many small ports of the North Channel of upper Lake Huron. One was the brand new MANITOU (C.107140), 137.2 x 24.2 x 9.1, 470 Gross and 297 Net, that had been built for the company in 1903 at Goderich by William Marlton. The other was the much older steamer HIRAM R. DIXON (U.S.95761, C.107600), which had been built in 1883 at Mystic, Connecticut, and which had been brought to the lakes about 1890 by Booth Fisheries Corp., Chicago. She was lengthened at Chicago in 1892, making her 147.2 x 20.6 x 9.0, 329 Gross and 255 Net. She was transferred into Canadian registry in 1901 in order to run for the new subsidiary, but unfortunately she was destroyed by fire near Michipicoten Island on Lake Superior on August 16, 1903.

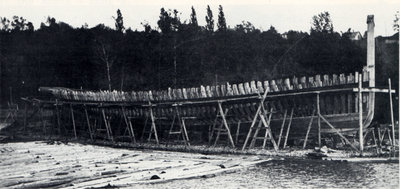

It is the autumn of 1903 and CARIBOU's hull is in frame at the Marlton shipyard at Goderich.

Whether the company had intended to build another ship anyway, or whether the decision to do so resulted from the loss of HIRAM R. DIXON, we may never know. Regardless, however, William Marlton began to construct another new steamer for the Dominion Fish Company Ltd. at his Goderich shipyard during the late summer or early autumn of 1903. She was to be very similar to MANITOU, although just a bit larger. Work on the ship continued through the winter months, and she was ready for service early in 1904. She was christened CARIBOU, and was enrolled as C.116249 at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, which was to remain her port of registry for her entire active career of forty-two years. The name given to her was appropriate in its reference to the animal which is native to northern regions, but was, we suspect, chosen specifically because of its similarity to the name carried by her near-sister MANITOU.

CARIBOU, unusual in that she received no major alterations of any nature to her hull or superstructure during her lifetime, was 144.8 feet in length, 26.6 feet in the beam, and 10.5 feet in depth, with these dimensions giving her tonnage of 597 Gross and 371 Net. Her hull was built of the best oak that could be found, and the fact that it remained sound and kept its sheer for so many years was a credit indeed to the builders at the Marlton yard. The new steamer was powered by a two-cylinder, fore-and-aft compound engine which was built for the ship by the Goderich Engine and Bicycle Company. It had cylinders of 17 and 34 inches, with a stroke of 26 inches, and developed 450 Indicated Horsepower or 43 Nominal Horsepower. (Some sources have reported the diameter of the engine's cylinders as 16 and 32 inches, but we do not believe that those measurements were correct.) Steam at 140 p.s.i. was created by one single-ended, coal-fired, Scotch boiler, which measured 12'0" by 12'0", and which was built in 1904 by the Polson Iron Works, Toronto.

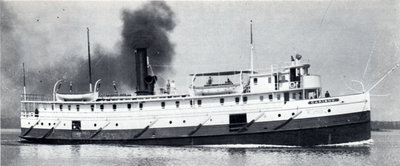

By winter, CARIBOU's hull is complete and her cabin is being built.

Two sources to which we have reference (one of them, surprisingly, being the 1932 American Bureau of Shipping register) have indicated that CARIBOU was (a) HIRAM R. DIXON. We suspect that such a report originated in the fact that certain fittings salvaged from the burned-out hull of the DIXON may have been placed in CARIBOU the next year. It is clear, however, that the hull of CARIBOU was of all-new construction, and that the engine which was placed in the ship was built for her and was not the machinery from the DIXON. Accordingly, we cannot help but believe that any suggestion of a substantial connection between the two ships must be unfounded.

CARIBOU was a very handsome steamer indeed. She had a stem that curved back slightly as it rose, and a heavy counter stern. Her main deck was fully enclosed and a number of portholes admitted light to the interior. The promenade deck had a closed rail at the bow, with a wooden post rail running around the rest of the deck. The passenger accommodations were located in the deckhouse on the promenade. On the upper (boat) deck, was a long clerestory to give light to the cabin below, and four lifeboats, two on each side. A tall and well-raked stack rose about two-thirds of the way down the steamer's length. A high pilothouse, with three large, round-topped windows in its front, was placed well forward on the boat deck, and the texas behind it contained crew quarters. Inconspicuous bridgewings protruded out from the sides of the texas roof. There were two rather short masts, the fore set close to the aft end of the texas, and the main placed well abaft the stack. The galley smokestack rose up on the port side of the pilothouse.

CARIBOU was launched virtually complete, and one excellent photograph taken by R. R. Sallows of Goderich appears to show CARIBOU on an excursion in Goderich harbour shortly after the launch. At that time, CARIBOU's hull and cabins were painted white, while her stack was black. A rubbing strake at the main deck level also was painted a dark shade, probably black. At the time the photo was taken, the ship's spars were not erected, but rather lay along the port side of the boat deck, no doubt secured there for protection during the long run up the open lake on her delivery voyage.

The recently-launched CARIBOU takes a turn around Goderich Harbour, 1904. All photos on this page by R. R. Sallows, courtesy David Hooton.

CARIBOU sailed from Goderich in due course of time for Owen Sound, where she was to be based along with MANITOU. She very nearly did not make it to her destination, however, for she encountered nasty weather and, with no cargo or ballast in her holds, she nearly succumbed to a heavy squall in the area of Cove Island as she was making her entrance into Georgian Bay. Battered by the storm, she finally made it to Owen Sound in safety, and there the finishing touches were put to her so that she could enter service in July 1904.

Together, MANITOU and CARIBOU ran a weekly service out of Owen Sound. Upbound, they called at Killarney, Killarney Quarries, Manitowaning, Little Current, Kagawong, Gore Bay, Meldrum Bay, Cockburn Island, Thessalon, Hilton Beach, Richards Landing, Sault Ste. Marie, Gargantua, Michipicoten River, and Quebec Harbour on Michipicoten Island. They would then return to the Soo and retrace their steps back to Owen Sound. This interesting route through the North Channel of Lake Huron was commonly known as the "Turkey Trail", because it wound this way and that through extremely dangerous waters, obstructed by rocks and shoals, and in and out of extremely small ports. In fact, the channel between the North Shore and Manitoulin Island is so tortuous that most mariners, accustomed to sailing the open lakes, would have nothing to do with the "Turkey Trail". These waters, however, were home to CARIBOU and MANITOU, and they were kind to both steamers over the years.

We do not know for sure how long CARIBOU wore her all-white hull, but it was not long, for we have never seen another photo of her with it. White may be a good colour for cruise ships, but it hardly is functional for a freighter, and both MANITOU and CARIBOU were combination freight and passenger boats, with the emphasis on the freight. Accordingly, both ships were given dark green hulls, which made them look much better. About the only other change of any consequence in the early years was the addition of a high wooden closed rail on the boat deck in front of the pilothouse of each ship. As built, each steamer had a pipe rail there, on which a canvas weathercloth usually was draped. However, when operating in fog or other nasty weather in the North Channel, the ship's master would usually stand outside the pilothouse, where his sight and hearing would not be obstructed, and where he more accurately could judge the boat's position from whistle echoes, sounds and smells from ashore, etc. The new closed rail would seem to have been designed solely for the comfort and protection of the skipper under such circumstances.

Perhaps, however, we should now spend some time to take a tour through the interior of CARIBOU. As far as we know, no description of the steamer's nether regions has ever before been published, and deck plans quite simply do not exist, so this will be a "first" for most of us. The description comes from two gentlemen who were intimately acquainted with CARIBOU for many years and, although the two ships were not exactly alike by any means, the same description could apply generally to MANITOU as well.

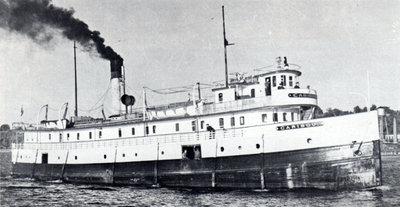

CARIBOU is downbound in Little Rapids Cut in a Young photo dating to the time of World War One.

Below the main deck, there was about ten feet of cargo space. In the forepeak, below the main deck, was located the deckhands' bunkroom, which had no ports or ventilation of any kind, and which was viewed with much disdain by all who came to know it. (Closed and unventilated quarters within the hull of a wooden steamer were something which had to be experienced to be believed.) Access to this area was by way of a hatch in the main deck forward.

Flanking the lower cargo space were the coal bunkers. They were filled from above through six manholes which were located just aft of the main gangways. Bunker coal was brought aboard at Owen Sound and the Soo by means of wheelbarrows, and the coal was then dropped down through the manholes in the main deck, a labourious process indeed.

The engineroom bulkhead ran from the keel to the second deck, penetrated on both sides by accessways to the bunkers. Immediately abaft the bulkhead was the stokehold area and boiler room. The engine and boiler were both mounted right down on the keel, the top of the engine protruding up through an open hatch into the after part of the maindeck cabin. The engineroom was located aft of the boiler room. The only showerbath aboard the ship was situated astern of the engineroom.

The galley was located on the port side of the forecastle, while the crew's mess and icebox were on the starboard side. The crew sat on a bench facing the ship's side as they took their meals. Forward of this was the icebox, kept cool by the infusion of huge blocks of ice obtained from the fish houses along the route. Food prepared for the passengers was passed up to the dining room by way of a hatch. One of our sources recalled that, on one occasion, just as he was lifting a huge pot of stewed prunes (!) up through this hatch, CARIBOU struck a rock in the channel. The cook, standing below, wound up wearing the prunes and our reporter kept out of sight for a few days. ..

The cargo elevator was located just abaft the main gangways, and was used to move heavy cargo in and out of the lower holds. (The necessity of stowing heavy cargo in the lower holds, regardless of the proximity of its destination, was borne home to Owen Sound vessel operators as a result of the loss of MANASOO in 1928 and HIBOU in 1936.) CARIBOU had a steam-operated elevating device, and the crew never found a cargo that the elevator could not handle. We have no specifications for the elevating gear, nor do we know for sure when it was installed, but it was there at least by 1932, and we suspect that it was installed much earlier.

Aft of this main deck cargo space was the machinery area, and then the foyer through which the passengers embarked or disembarked via the smaller aft gangways. Upon entering the ship here, the passengers would stop at the purser's wicket and then proceed to the passenger cabin on the promenade deck via the stairway which ran up over the engine. The open engine pit here was surrounded by a closed railing which was capped by a polished wooden handrail. In the stern section of the main deck were located the purser's and steward's offices, together with their cabins, and also the accommodations for the engineers and the firemen.

The main smoking and observation lounge for the passengers was located in the forward section of the upper cabin. Immediately abaft the lounge was the main dining area, with the pantry on the port side and a cabin for the waiters, waitress and pantrymen on the starboard side. During the summertime, the usual ship's crew of master, two mates, two wheelsmen, four deckhands, two engineers, two firemen, purser, steward, waitress and cook, was swelled by the addition of three waiters and two pantrymen. These five extra crew usually were students, and it was necessary to have them aboard in order to look after the additional passengers who appeared in the high season. Many were the young men from the Owen Sound area who had their first jobs afloat working summers on MANITOU and CARIBOU.

Aft of the dining room was the main hallway, which was flanked by two rows of staterooms. About two-thirds of the way aft through the cabin, the hallway was interrupted by the smokestack casing, and from this point, short passageways ran out to the promenade deck on each side. In the after end of the passenger cabin were the ladies' and gents' toilets and also the after lounge, the latter containing an upright piano. The staterooms, small but comfortable, were equipped with two bunks (upper and lower), a washstand, and a single stool. Under the lower bunk was space in which suitcases might be stowed. There was running water in the cabins for use in the washstand, but of course there was no space for a watercloset, and hence the positioning of the public toilets "down the hall".

It is recalled that, on one particular trip, CARIBOU encountered rough weather whilst out on Lake Superior. A rather ample woman passenger, beginning to suffer the effects of "mal de mer", decided to retire to her cabin. Just as she opened the door to her stateroom, the ship went into a really good roll. The woman lost her balance and was propelled across the sloping cabin. She came to rest in a sitting position in the wash basin which, under the unexpected weight, was ripped free not only from the cabin wall but also from the waterpipes. The resulting commotion soon brought an assortment of crew members to the scene, and the engineer finally succeeded in stemming the flood of water and restoring order to the plumbing. CARIBOU's master, of whom we shall speak at length later, was overheard to comment that, in the course of the escapade, the woman passenger had forgotten all about her seasickness!

The main hallway in the upper cabin was lighted by means of a long clerestory, in which the various panes of glass were of different colours. With the sunshine beaming in through the skylight during the day, this produced a very unusual multi-coloured effect in the hallway. At night, the lights shining out onto the boat deck through the coloured glass also produced a most striking effect, although the government inspectors took a dim view of the presence of green and red glass in the clerestory, thinking that it was likely to be mistaken for the ship's sidelights.

Cargoes were particularly heavy during the spring and fall months, when very few passengers took passage in CARIBOU. As a result, cargo was stowed not only in the holds and on the main deck, but also, on occasion, in the passenger cabins and even up on the boat deck and down in the engineroom. CARIBOU's last master recalls occasions when sleighs and empty fishboxes were carried on the boat deck. Needless to say, under such circumstances, it was to be expected that some of the glass panels in the clerestory would be broken and this is, in fact, what happened. As well, panes would be broken occasionally under more normal circumstances, and as the sections of glass were broken, they were replaced with plain clear glass, thus interrupting the patterns of colour.

CARIBOU's texas cabin, located just behind the pilothouse on the boat deck, was not large, but it did contain quarters for the master, the two mates, and the two wheelsmen. The accommodations there were far from luxurious, as of necessity were all crew and passenger quarters on the little ship, but they were adequate for the purposes.

The steamer's steering was direct (i.e. of the "armstrong" variety, with no steering engine fitted), and for many years it was cross-chained. One of our "reporters", Gordon Macaulay, recalls that on one occasion he was handed the helm of CARIBOU as the ship was preparing to enter the small harbour at Thorn-bury (on the western shore of Georgian Bay). To prevent her from shearing to port, he turned the wheel to starboard and promptly turned the ship in what was almost a complete circle. The captain commented that it was indeed lucky that there had been lots of water under CARIBOU at the time!

CARIBOU and MANITOU were an important part of the Booth Fisheries operations, in that the many tons of fish that they transported were sent by rail into the U.S. Sometimes the little steamers would pick up dozens of 225-pound crates of fish at their various ports of call. In 1909, Booth reorganized its Canadian operations, and although the Dominion Fish Company Ltd. remained the registered owner of CARIBOU and MANITOU, a corporation known as the Dominion Transportation Company Ltd. was formed to operate the steamers. We shall be hearing more about this company as our narrative proceeds.

It is true that CARIBOU and MANITOU were very similar in both size and appearance, but there were some differences, perhaps the most noticeable of which lay in their pilothouses. CARIBOU's pilothouse had three big windows in its front, and the house was narrower but taller than the texas. MANITOU had five small windows in her pilothouse front, and it and the texas were contained within the same deckhouse. Another differentiating feature was the smokestack, CARIBOU's being rather larger and taller than that carried by MANITOU.

Both CARIBOU and MANITOU usually cleared Owen Sound on the first trip of the year about May 1st or shortly thereafter, and their first few trips were very busy as they brought fresh supplies to the small communities which had been completely isolated during the winter. For insurance purposes, their last trips of the year had to be timed so that they cleared downbound from the Soo by midnight on November 30th. There were occasions when this was not possible because of inclement weather, in which case the steamer might back away from the dock at about 11:45 p.m. on November 30th, move several hundred feet out into the river, and then drop the hook to await improved weather.

Although several sections of the steamer's route took her into exposed situations, CARIBOU was an extremely lucky ship and never suffered a major accident. Perhaps the closest she came to real danger was in the Great Storm of November 1913. Upbound across Georgian Bay, she was caught in the tempest and it was only with great difficulty that she fought her way through to the comparative (but dangerous) shelter of the North Channel. She finally made port at Manitowaning and luckily she suffered relatively little damage apart from the breaking of a number of the portholes in the main deck cabin. Another close call for CARIBOU came on September 15, 1928, when she was outbound from Owen Sound. A few hours out of port, she passed the inbound steamer MANASOO, the former MACASSA, which was in her first season of operation for the Owen Sound Transportation Company Ltd. The weather was heavy, and a short time after the passing of the two ships, MANASOO developed a heavy list, rolled over and sank off Griffith Island, with the loss of sixteen lives. The crew of CARIBOU had a feeling that all was not well with MANASOO, but the little CARIBOU was making extremely heavy going of it at the time, and she could not turn about to see if everything was all right with the other ship. CARIBOU's master finally got her into shelter under Cape Croker, and there she remained for three days until the weather moderated sufficiently for her to proceed on her way.

There were a number of occasions when CARIBOU was delayed through having to shelter from heavy weather, and in those days when there was no radio communication with the steamers (CARIBOU only received a radiotelephone set in her last few years of service), it was possible for the ship to disappear for several days while the shore staff worried about her whereabouts. This happened many times, but CARIBOU always turned up safely. On occasion, if rough weather was encountered after leaving Owen Sound, CARIBOU's master might seek shelter behind Hay Island and then Griffith Island, where he could beach her and go ashore to do some deer hunting until the weather improved. After a delay that might be as long as three days, CARIBOU would resume her trip, probably arriving at Killarney in beautiful weather. It is no wonder that, although CARIBOU always completed her trips, she and MANITOU were not always running exactly to schedule!

MANITOU was not as lucky as was CARIBOU, and she sustained at least two serious accidents. She suffered fire damage and sank at her dock at Owen Sound on February 2, 1913. She also suffered a serious grounding on a late-season trip in the mid-1930s; above Hilton Beach on St. Joseph Island, she struck a rock, climbed all over it, and rolled on her side, bow down. She eventually was freed, but not without lasting damage. Strangely enough, CARIBOU arrived in the other direction whilst MANITOU was up on her rock, and tried to lend assistance, but CARIBOU herself stranded and had to be rescued before the salvors turned their attention to the more severely damaged MANITOU.

Apart from the incident involving the joint grounding of CARIBOU and MANITOU in the mid-1930s, we have been able to find only one official report of an accident involving CARIBOU. That occurred on July 28, 1922, when she ran aground in the Nelson Channel near Richards Landing. Damage was not severe, but we have no other details.

Being wooden ships, CARIBOU and her near-sister were always at risk to the peril of fire, although fortunately neither of them ended her days in flames as did so many of the wooden lake steamers. Regular fire patrols were carried out through the cabin each night, and it was not infrequently that the crew was called upon to chuck overboard a blazing mattress or other contents from the stateroom of a passenger who had partaken of one too many nightcaps before retiring. On such occasions, the crew was sorely tempted to toss the passenger over the side along with the cabin contents, but we are not aware of such drastic measures ever having been taken, although no doubt some rather harsh words passed between the parties concerned.

Once in a while, however, CARIBOU tried to do herself in. She had a rather capricious habit of catching fire occasionally in the area where the stack casing passed up through the main cabin. This undoubtedly resulted from an insufficiency of proper insulation in the area. Fortunetaly, [sic] however, the location where this tended to happen was very conspicuous and it was a simple matter for the crew to attend and put out the fire before it became a major conflagration.

CARIBOU and MANITOU actually served as fire-fighting ships themselves on at least one occasion. One summer during the early 1930s, a major forest fire broke out in the area of Otter Head on the north shore of Lake Superior. Although Otter Head was considerably out of the way for them, CARIBOU and MANITOU were the only steamers trading regularly anywhere near the fire site, and of course there was no such thing as waterbombing from the air in those days. Both ships were commandeered by the provincial government, and they spent much of the summer ferrying supplies, hose, pumps, tents, horses and mules, and of course men, to the inhospitable shore where they were put off by way of barges to begin the overland trek to the fire camps. While the unloading process was going on, clouds of smoke and sparks from the fire would swirl around the ship, and it was the passengers who prowled the open decks with pails and wet mops in order to smother any embers which might fall on board.

No matter what one might say about CARIBOU herself, it was the people who sailed her who made her what she was. They truly cared about the well-being of the ship, her passengers and her cargo, and none cared more than did her long-time master, Captain Arthur A. Batten, who commanded her continuously for thirty-two of her forty-two years of service. He took over as her master about 1909 and stayed in her until her retired in 1940. He was a kindly and loquacious gentleman, but he had some very strong ideas on how a steamboat should be run and that is exactly how CARIBOU was operated. There have been many accounts of how Capt. Batten perfected the art of running CARIBOU over the "Turkey Trail" despite inclement weather, but none, perhaps, can equal the tribute paid by Capt. Horace Beaton (of HAMONIC fame) in describing a trip he took on "a small boat from Sault Ste. Marie to Owen Sound". "We left the Soo late afternoon and the next morning I had my breakfast and I knew the second mate was on watch and I went up to the wheelhouse. The second mate and the wheelsman were there and, as it started to get very foggy, they started blowing fog signals on the whistle. It wasn't long before the captain appeared and started walking back and forth in front of the wheelhouse. The second mate kept blowing the fog signal.

"A short time later, the captain, (still) walking back and forth in front of the open wheelhouse window, said 'I say, I say, Buck, we are getting near Kagawong. I smell the cedars.' After that, he walked to the ship's side, gave three pulls on the signal whistle to the engineroom. This was to check the engine down. He then came back to the open window and said 'Get the lines ready to tie up, Buck.' He had his watch in his hand, and at the open window he said to the wheelsman 'Hard-a-port'. The wheelsman swung the wheel around a few turns, turning the ship to the left. The captain then said 'steady.' The wheelsman steadied the ship on a compass heading.

"The fog was still so thick I'm sure you could not see over fifty feet. In a matter of three or four minutes, we pulled alongside the dock at Kagawong. I told the foregoing story to make a comparison of the early days with the modern equipment they have for navigating today. Here was a captain with only a watch and magnetic compass and a lot of instinct. I have a great respect for a captain like this... and his great wealth of knowledge. He could smell his way through the fog."

Of course, even if Capt. Beaton did not identify them, there is no doubt that he was referring to CARIBOU and Capt. Arthur Batten. The "I say, I say" was one of Capt. Batten's trademarks, so to speak, and although he did not dwell on his own accomplishments (saying only that his success with CARIBOU was "done by ear, by nose and by God"), he did like to receive praise for his work, and he would have been flattered by the honour done him by as distinguished a master as Capt. Beaton. In addition, many other persons have commented, verbally or in writing, about the manner in which Capt. Batten handled CARIBOU. Without exception, they saw him as being completely in touch at all times with the ship and with the waters which she sailed.

Not very many steamer lines can boast having had even one skipper like Capt. Batten, but the Booth fleet had two of them. MANITOU was commanded by Capt. Norman J. McCoy, who took over command of that ship at about the same time as Arthur Batten assumed command of CARIBOU. The two were very different in many ways, but they enjoyed the same communion with ship and environs, and both were highly respected by the vessels' owners as well as by the passengers and all other who depended upon the steamers.

In 1933, the company honoured Captains Batten and McCoy for the 25 years which each had spent in command of his steamer. The boats met regularly on Wednesdays at Manitowaning, and it was arranged that on one particular trip each was to arrive a bit early (something of a feat under any circumstances) so that preparations could be made. Both skippers were spirited off their ships (McCoy lived in the town) and then back at the right time after CARIBOU's cabin had been decorated and the food prepared for the occasion had been laid out. Then, with a large group of specially invited guests in attendance, the two masters were feted for their rather impressive accomplishments. Both were to serve for many more years, and each could boast that he never lost a ship, or the life of a single passenger or crew member, whilst in the company's service.

CARIBOU would often carry a full load of cabin passengers, and in many cases she would carry a number of deck passengers as well. These latter persons might well be making only one segment of the trip (rather than the full voyage) and, although they might take meals aboard the steamer in the regular manner, they would have to find their own sleeping quarters, whether on bales of hay in the hold, or wherever. For instance, back in the 1930s, when a number of mines and pulpwood operations were active in the Michipicoten area, there was a large movement of persons between the Soo and Michipicoten. The fare by boat for the overnight trip was $7.70, which was five cents cheaper than the same trip by train; although the fare included meals and berth, there seldom was stateroom accommodation for all who wished to make that section of the trip.

As we have mentioned, the Dominion Fish Company Ltd. was the registered owner of CARIBOU for many years. The 1929 Canadian register showed the owner as Booth Fisheries Canadian Company Ltd., Toronto, while in 1938 the owner was the newly-formed affiliate, the United States and Dominion Transportation Company Ltd. In 1938, the ownership of CARIBOU and MANITOU passed to the Dominion Transportation Company Ltd., Owen Sound, and this firm was to remain the registered owner until CARIBOU was retired. During the 1920s or early 1930s, the black stacks of the company ships were embellished with a red diamond, upon which the letters 'D.T.Co.' appeared in white.

Meanwhile, in 1921, a rival firm known as the Owen Sound Transportation Company Ltd. had been formed, and it operated almost exactly the same route, using steamers such as MICHIPICOTEN (its first boat), ISLET PRINCE, KAGAWONG, MANITOULIN and MANASOO, and the motorship NORMAC was added in 1931. With the advent of this new company, there was much active competition with the ships of the Dominion Transportation fleet (which, from 1928 until she was lost in 1936, included HIBOU), and CARIBOU and MANITOU often found themselves racing against other ships to see who would get to pick up the cases of fish waiting at the various ports.

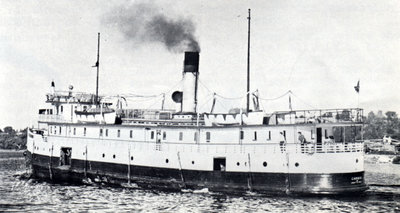

Two scenic views of CARIBOU at Owen Sound in 1944 were taken by Gordon Macaulay.

The murderous competition was ended in 1936 when Dominion Transportation and Owen Sound Transportation agreed to operate a "pool service" which, in effect, brought all the ships together into one fleet. In 1937. Ivor Wagner, who was an executive with Booth Fisheries in Chicago, bought Dominion Transportation from Booth, and he moved to Owen Sound in 1938 to take over the management of the company. The pool arrangement continued until 1944, when the Dominion Transportation Company purchased the stock of Owen Sound Transportation. Although Dominion remained thereafter the holding company, Owen Sound Transportation continued to exist as the operating entity.

During the mid- to late-1930s, CARIBOU and MANITOULIN ran the summertime "cruise" service together, with MANITOULIN doing the run in five days and sailing Monday evenings from Owen Sound, while CARIBOU took six days for the round trip and sailed Thursday evenings. The all-inclusive fare for the trip in CARIBOU in 1937 was the princely sum of $37.50 per person!

MANITOU was retired from service at the end of the 1939 season, and Captain Norman McCoy retired with her. Age was taking its toll on both of the steamers and their masters by that time, and Capt. Arthur Batten retired from CARIBOU at the close of the 1940 season, after completing 32 consective [sic] years as her skipper. He was coming up on 75 years of age at the time of his retirement. His replacement was Capt. Richard Tackaberry, who had started in CARIBOU back about 1932 as wheelsman under Capt. Batten. He, too, developed an extraordinary ability to sail CARIBOU on her difficult rounds in all types of weather without untoward incident.

The Owen Sound Transportation Company had begun in 1930 to run a summer ferry service between Tobermory and South Baymouth, and the old Dominion Transportation boats became involved in it after the advent of the pool arrangements in 1936. MANITOU spent her last few summers running this ferry route, along with NORMAC, and after MANITOU was retired, CARIBOU went onto the ferry service during the busy months of July and August, leaving MANITOULIN to run the North Channel and "cruise" route alone. (The Lake Superior leg of the long route was discontinued in 1942.) CARIBOU, however, would swing back onto the "Turkey Trail" in the spring and fall of each year.

CARIBOU and NORMAC were hardly the most suitable boats for the Manitoulin Island ferry service, but they were the only ships available and they did the best they could to handle what sometimes were extremely long lines of people with cars waiting to make the trip. CARIBOU could tuck thirteen cars onto her freight deck each trip, and NORMAC could take twelve. Despite the fact that the boats would cross back and forth as fast as they could, and often on a 24-hour-a-day basis on weekends, they often were hard-pressed to move all of the prospective passengers with autos that were lined up on the wharf. During those busy summers, Capt. McCoy often came back out of retirement to serve as relief skipper on CARIBOU.

By this time, CARIBOU was wearing what had become the usual colours after the merging of the two companies. Her hull was black to the freight deck rail, while her upper works were white. She carried fancy nameboards on her bows and also across the dodger in front of the pilothouse. Her stack was painted buff, with a narrow blue band and a black smokeband at the top.

CARIBOU had carried several different steam whistles during her life, but the most famous was the one she blew during the last few years of her life. It had started out on a Bruce Peninsula sawmill, and when the mill burned, the whistle was salvaged and eventually it was placed aboard the steamer HENRY PEDWELL (30), (a) CHARLES LEMCKE (13), (c) KAGAWONG (32), (d) EASTNOR. The whistle then made its way over to MANITOU, and it served as her voice for many years. It was a big whistle, and it produced a deep, loud roar on a full head of steam. Capt. McCoy always used it to full advantage, easing in and out of each whistle blast rather than jerking the lanyard which ran from the pilothouse to the whistle valve. When MANITOU was retired in 1939, the whistle was placed aboard CARIBOU, and she finished out her days with it.

By 1946, the poor little CARIBOU was just about played out. Her wooden hull and cabins were falling victim to old age, and more and more maintenance was required to keep her in acceptable condition. (This could readily be confirmed by anyone who occupied an upper berth in one of the staterooms in bad weather during CARIBOU's later years, for the rainwater would pour down through the aging deck above.) As well, the freight service to the North Channel was of considerably decreased importance in that roads had come to many of the little ports, and the ships were no longer needed to carry all the essentials to the residents there, or to ferry their produce back to "civilization". And CARIBOU was no longer needed on the Manitoulin Island ferry service after NORISLE was built for that route during 1946. As far as the summer "cruise" service was concerned, MANITOULIN was quite capable of handling that all by herself.

Accordingly, the company with regret made the decision to take CARIBOU out of service, and she made her last sailing from Owen Sound on Saturday, September 14, 1946. She had been scheduled to sail at 11:00 on Friday evening but, mindful of old superstitions, Capt. Tackaberry made certain that she did not clear until after midnight. She did her old "Turkey Trail" route, with farewells from many old friends along the way, and arrived back at Owen Sound on Thursday, September 19th.

As was only fitting, Capt. Arthur Batten was on board for the final trip as honourary master, and Capt. Tackaberry was there too. Tending the engine was chief engineer Jack Glover, who had been in CARIBOU for seventeen years himself. CARIBOU's purser for the last trip was Mickle Macaulay (father of Gordon), who was agent for Dominion Transportation for over half a century, and who had been purser aboard CARIBOU on her very first trip back in 1904. Many of the rest of the crew were veterans of the service as well, and even cabin stewardess Elizabeth Townsley had been in CARIBOU for nine years.

CARIBOU's boiler was not yet cold at the conclusion of that last, nostalgic trip when both the "Owen Sound Sun Times" and the "Toronto Telegram" published farewell tributes to the steamer and her many years of service. The articles mentioned how faithfully CARIBOU had served her intended route, and the reputation she had earned among the people to whom she served as a lifeline for their isolated communities. At the time, many people recalled the various strange cargoes that CARIBOU and MANITOU had handled, including, on occasion, cattle which strayed during loading or unloading, which fell overboard, or which made their way into unusual places aboard ship. (One even found its way into MANITOU's stokehold and proved very difficult to remove.)

CARIBOU spent the winter of 1946-47 at Owen Sound and was sold in the spring to one M. Dacey of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. She sailed to the Soo under her own steam and was tied up in a slip which had been dredged for her on the shore of the old channel some five miles east of the Soo. Her new owner intended to convert her into a summer resort facility, using her cabins and dining room, and with dancing on the freight deck, but nothing ever came of these plans, and the old steamer gradually fell into a sorry state of disrepair. She was dropped from the Canadian register in 1955, with the notation that the ship had been abandoned.

Eventually, the area in which CARIBOU lay was developed for housing, and the landlocked and rotting ship was considered to be an eyesore. Her superstructure was dismantled and the hull itself was burned. The remains lay there for several further years, but were considered to be a danger for children playing in the vicinity, and so the last of CARIBOU was bulldozed into oblivion during the autumn of 1962.

Aside from memories of the steamer, something else of CARIBOU lived on for a number of years, and that was her voice. When CARIBOU was retired, her famous whistle was transferred over to MANITOULIN, where it served until she was retired at the close of the 1949 season. It then was moved over to the nwely-built [sic] NORGOMA, and it was blown by her until her steam machinery was replaced by a diesel engine in 1964. In fact, blown by air, it lasted a while longer, but eventually was removed as this arrangement was not satisfactory. CARIBOU's steering wheel also was saved, and found its way to the Great Lakes Historical Society's museum at Vermilion, Ohio.

No memory of CARIBOU, however, could be considered complete without including Capt. Arthur Batten, and so we conclude with a last fond look at both the ship and her master. On one occasion, CARIBOU was caught in a heavy fog on the St. Mary's River, and she was blowing fog signals as were several other much larger steamers in the area. Feeling his way through the fog, Capt. Batten edged CARIBOU along until suddenly a long black hull loomed up ahead; it turned out to be the Cleveland-Cliffs steamer NEGAUNEE. Not at all timid under the circumstances, Capt. Batten moved CARIBOU right up to the freighter and tied up alongside her to await an improvement in the weather. A deckhand came along NEGAUNEE's deck and, no doubt shocked to see the little CARIBOU tied up there, shouted over "What are you doing here, mate?" Batten, who was, as usual, wearing his uniform cap with the word 'captain' in large letters surrounded by oak leaves, pointed to it and replied, somewhat testily, "I'm the skipper on this ship! Can't you read?"

Ed. Note: We extend our gratitude to everyone who assisted us in the preparation of this feature. Special thanks go to Ron Beaupre, who interviewed Gordon Macaulay and Capt. Richard Tackaberry to obtain for us their invaluable comments concerning CARIBOU and her service, and we thank these gentlemen for their generosity in sharing their recollections with our readers.

In addition, we thank all those persons, many of whom no longer are with us, who over the years recalled for us their very own personal experiences with CARIBOU. For some of them, their very first job was in the steamer. Special mention must be made of the extraordinary early photos of CARIBOU, taken by R.R. Sallows, which were made available through the courtesy of David Hooton. The two beautiful late-career views of the ship at Owen Sound, taken by Gordon Macaulay, were provided courtesy of Ron Beaupre.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.