Table of Contents

To those of us who were chasing lake ships back in the years before the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, some of the most familiar lakers were the many canallers which plied their trades through the small locks of the old St. Lawrence Canals. In fact, although a few of the canallers were of more modern vintage, most of them had been built back in the days before the opening of the fourth Welland Canal, when numerous small locks had to be traversed in the journey up or down the Niagara Escarpment in order for a steamer to move between Lakes Ontario and Erie. Today, many marine enthusiasts are persons who have taken up the interest within the last quarter-century, and who may never have seen a true canaller in operation. And even if they have carefully examined photos of those famous little vessels, they have little appreciation for the art and skill that was involved in navigating the canallers through narrow and winding channels, down rapids, through seemingly impossibly-narrow bridge draws, and in and out of lock chambers that were but infinitesimally larger than the hulls of the ships themselves.

It is for this reason that we like to write about some of the canallers in this day when such ships are, with only a few exceptions, almost extinct. In addition, preparing a feature on canallers brings back our own memories of those days when we used to chase them around the canals...

One of the major operators of canallers in years gone by was the Mathews Steamship Company Ltd., Toronto. This fleet was founded back in 1856 by James Mathews of Toronto, and it later became the partnership of J. and J.T. Mathews. The partnership continued until 1902, when James Mathews retired. His son, Alfred Ernest Mathews, then joined with James' brother J. T., in forming the Mathews Steamship Company. This firm was incorporated at Toronto on October 15, 1905, with capital of $250,000. J. T. Mathews did not remain with the company for very long, and he died at Toronto on May 21, 1919.

A. E. Mathews was dedicated to the lake shipping business. He built his company into a major competitor, with a fleet that was composed of both upper lakers and canallers. He had been responsible for the return of the old "Wolvin" canallers to the lakes after the conclusion of World War One, and in the early 1920s he was associated with James Playfair in several joint ventures, although by 1925 Mathews and Playfair had severed their connections, each going his own way. Ten new vessels were added to the Mathews Steamship Company's fleet during the 1920s.

Two of these new ships were canallers built by the Smith's Dock Company Ltd. of South Bank-on-Tees (Middlesbrough), England. This yard built a number of canallers for Canadian lake fleets, but its most famous products destined for the lakes were the eleven canal steamers which comprised a group of virtual sisterships which the yard completed in 1928 and 1929. Although these boats were "mass-produced", as were many canallers built by British yards for the lakes, they had a more appealing and less utilitarian appearance than did many others.

The first five ships of the specific Smith's Dock group with which we are concerned were built for the Hall Corporation in 1928, and were AYCLIFFE HALL (Hull 845), EAGLESCLIFFE HALL (I) (846), C0NISCLIFFE HALL (I) (847) , WESTCLIFFE HALL (I)(840) and ROCKCLIFFE HALL (I)(841), whose keels were laid in that order despite the hull numbers. In 1929, MEADCLIFFE HALL (868) and GEORGE L. EATON (II)(869) were completed for the Hall Corporation, while Hull 870, TEAKBAY, was built for the Tree Line Navigation Company Ltd. Hulls 871 and 872 were FULTON and SOUTHTON, the two which were built for Mathews, while the last of the group of sisterships was Hull 873, delivered to the Foote Transit Company Ltd., Toronto, as F. V. MASSEY. It is not known with any degree of certainty, but there exists the possibility that F. V. MASSEY was built for Capt. James B. Foote as payment for that entrepreneur's efforts in arranging for the other contracts to go to the Smith's Dock Company.

No matter what the situation with the MASSEY, it is an indisputable fact that FULTON and SOUTHTON were amongst the best canallers that ever graced the Mathews fleet. Apparently exact sisterships, they were 253.0 feet in length, 44.1 feet in the beam, and 18.6 feet in depth, with tonnage of 1892 Gross and 1190 Net. "Underdeck" tonnage was 1705. Each was powered by a triple expansion steam engine with cylinders of 15, 25 and 40 inches and stroke of 33 inches, which produced 750 Indicated Horsepower (sometimes shown as 800) and 95 Nominal Horsepower, giving a service speed of 8 1/2 knots. Steam at 180 p.s.i. was produced by two single-ended, coal-fired Scotch boilers which measured 10'6" by 10'10". The engines were manufactured for the ships by the Smith's Dock Company Ltd., while the boilers were made by Blair & Company Ltd. (It is interesting to note that, in latter years, the diameter of FULTON's high-pressure cylinder was shown as 15 1/4 inches, and that of SOUTHTON as 15 3/8 inches.)

FULTON was completed at South Bank during April of 1929, while SOUTHTON was ready in May. Both ships were enrolled at Middlesbrough, with official numbers Br.160721 and 160722, respectively. It was not uncommon in those days for British-built canallers to retain their British registry, at least for the early years of their lake service. It should be noted, however, that British and Canadian registry numbers were taken from the same sequence, so that no new number was required if such a vessel were later brought into Canadian registry.

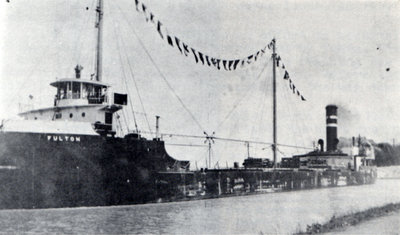

An unusual photo caught FULTON, dressed for some occasion, downbound in the old Welland Canal whilst owned by the Mathews Steamship Co. Ltd.

The Mathews fleet normally gave its vessels names which incorporated the suffix 'ton', but there is no obvious explanation as to how the names FULTON and SOUTHTON were chosen for these ships. As far as we know, there has never been a town in Canada bearing either name. SOUTHTON was probably chosen for no other reason than to be a companion to NORTHTON, which was the name given to a canaller built for Mathews in 1924 at Newcastle. FULTON has no obvious relation to anything connected with the Mathews fleet, but may have been a reference to the famous inventor, Robert Fulton, who was associated with shipping on the Hudson River in the early 1800s.

FULTON and SOUTHTON had virtually sheerless hulls, as did most canallers of the period, with bluff bows, a straight stem, and a heavy but pleasing counter stern. Each carried a raised forecastle, with a closed rail protecting part of the forecastle head, and the anchors were placed very far forward, housed in round-topped pockets cut into the forecastle just above the level of the spar deck.

On the forecastle head was set a wide but rather shallow texas cabin which contained the master's quarters and office, the rest of the deck crew and the mates being accommodated in the forecastle. Three portholes were cut into the forward bulkhead of the texas (one to starboard, two to port), and at its centre were displayed her builder's plate and bell. The bridge deck above sported flying navigation wings supported on closed struts tastefully incorporated into the sides of the texas, and the front of the bridge deck was curved outward into a gentle bow to provide additional deck space in front of the pilothouse.

The round-fronted pilothouse sat as far back on the bridge deck as possible, and featured five very large windows in its front, which gave excellent visibility, especially for canalling. A broad sunvisor kept the sun out of the eyes of those on watch. An open rail ran around a small section of the monkey's island atop the pilothouse roof where a large binnacle was set, but no navigation was done from there. A protective canvas weathercloth could be hung on the open rail across the front of the bridge deck and stretcher-frames were provided so that, in hot summer weather, canvas awnings could be set to shade the entire open area around the pilothouse.

The steamer's quarterdeck was flush with the spar deck, and a closed steel bulwark ran around the stern to shelter the cabin located there. The after cabin itself was a large structure which accommodated the engineroom officers and crew, the stewards and galley staff, and also contained the crew's and officers' messrooms. The boat deck overhung the sides of the cabin all the way around to give some shelter from the elements, and this was a feature which very few British-built canallers boasted. Two lifeboats were carried on the boat deck, and from it also rose the tall and fairly heavy, but only slightly raked (3/8 inch to the foot) stack, which sported a prominent raised cowl at its top. On either side of the stack were large freshwater storage tanks, and two large ventilator cowls stood directly ahead of the stack. The bunker hatch was set far forward on the boat deck, with the bunkers running down through the forward end of the boilerhouse section of the after cabin.

Each steamer had six large hatches set into her spar deck to provide access to the two cargo holds. The sixth hatch was particularly large and was raised slightly above the deck. There were six steam winches for the mooring lines and a steam windlass as well, the winches also being used to handle the cargo booms and hoisting cables. The heavy pole foremast was set immediately abaft the pilothouse and it carried one cargo boom. An equally heavy mainmast was set between the fourth and fifth hatches, and it was equipped with two booms, one slung forward and one aft. The booms were used to handle a variety of cargoes but were especially useful in the loading of pulpwood. When not being used as the vessel was running, the booms normally were lowered to a position parallel to the deck; the tips of the foremast boom and the forward boom on the main almost touched and were secured to a small post braced on the deck, while the after boom on the main was secured just forward of the boilerhouse.

FULTON and SOUTHTON were painted in the usual Mathews Steamship Company colours, with a black hull. The forecastle rail and the cabins were white, and the masts were buff. The stack was black with two narrow silver bands, this same design being carried on the funnels of the ships of the Misener fleet after it acquired some of the Mathews ships in later years. The name appeared in large white letters on the bow, the letters slanted slightly forward to give an impression of speed (something that most steam canallers lacked). The only photo which we have of either of these steamers in Mathews colours shows only the name painted on the forecastle, but it is likely that the famous Mathews monogram was eventually added. The logo featured a large white 'M' inside a white-edged, ringbuoy-type double circle which at first was painted in the form of ropes, complete with a bow at the bottom. The name "Mathews S.S. Co. Ltd.' appeared in small white letters around the ring.

FULTON and SOUTHTON operated successfully for Mathews, and we know of no troubles afflicting them during this short portion of their careers. As time was to prove, these two steamers and all of their numerous sisterships were good carriers, lasting right up until the opening of the Seaway, and several eventually wound up on salt water. Not only these eleven ships, but also the trio of WALTER B. REYNOLDS (II), JOHN H. PRICE and MONT LOUIS, which were delivered to the Hall fleet by Smith's Dock in 1927, were sometimes referred to as "The Dishpans" because of the fact that their hulls were constructed with scantlings that were much lighter than those used in most other canallers. The detractors of the design, who coined the "Dishpan" nickname, undoubtedly derived a certain amount of gratification from the 1928 incident in which EAGLESCLIFFE HALL began to break apart on Lake Erie in heavy weather and only was saved when her crew stretched mooring cables down the deck to strap the ship together until she could reach port. The sinking of AYCLIFFE HALL in a collision on Lake Erie on June 11, 1936, may also have reinforced the notion that the sisterships were not sound, but in reality they were quite successful and no other untoward incidents were recorded.

But if FULTON and SOUTHTON did well, their owner did not. The simple fact of the matter is that Alfred Ernest Mathews overextended the resources of his company during the 1920s. A lot of new ships were built, including the big, handsome upper lakers MATHEWSTON and ROYALTON, and Mathews had mortgaged many of his existing vessels in order to pay for them. When things started to go sour for the shipping industry during the summer of 1929, Mathews found himself in a precarious position, and the onset of the Great Depression after the stock market crash of October 1929 sealed the company's fate. The company was unable to get its act together and was forced into receivership. On February 10, 1931, the Mathews Steamship Company was adjudged bankrupt by the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Ontario in Bankruptcy, upon petition of the Toronto Dry Dock Company, which had not been paid for certain repair work it had done, and the fleet finally was sold off by late in 1933. A. E. Mathews himself had been removed from the company's offices in the C.P.R. Building at King and Yonge Streets, Toronto, partially as a result of some rather probing enquiry into his transfer of his big (151 feet) private steam yacht CONDOR from his personal ownership to registry in the company's name not long before the bankruptcy, and certain moneys which Mathews personally owed the firm and which never were paid.

By this time, however, FULTON and SOUTHTON had long since ceased to be part of the fleet. One of the company's secured creditors was the Smith's Dock Company Ltd., South Bank-on-Tees, which had an unpaid interest of $217,119.42 resulting from the construction of the two boats. Rather than standing in line and taking its chances on any recovery that might be received upon the break-up of the fleet, Smith's Dock simply repossessed FULTON and SOUTHTON, thus freeing them from the legal quagmire.

What happened thereafter is a matter of some rather considerable conjecture. It would appear that the repossession occurred in 1931, and the ships were then transferred to the ownership of Beaver Industries Ltd. Some sources reported that this firm was a subsidiary of the Smith's Dock Company, formed to hold the ownership of the two boats until they could be sold to other lake operators. On the other hand, Beaver Industries Ltd. was the name of a firm which was operated by one of Canada's most successful entrepreneurs of all time, Lord Beaverbrook, whose main interests lay in the newsprint and pulpwood trades, and this is thought to be the firm which actually took over ownership of FULTON and SOUTHTON. Seeking Canadian names for the two steamers, the company renamed FULTON as (b) BROWN BEAVER in 1932, while SOUTHTON became (b) GREY BEAVER, referring to the two differently-coloured species of the big rodent which was and still is Canada's national animal.

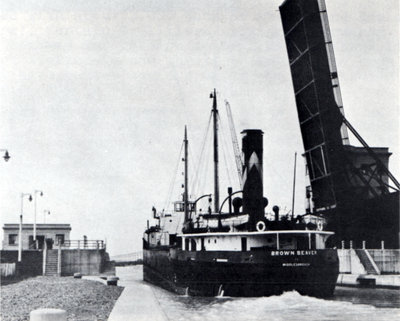

An extremely rare Welland Ship Canal official photo shows BROWN BEAVER, in Hall colours, upbound at the Thorold South guard gate, May 31, 1932.

Beaver Industries Ltd., however, was not in the business of operating lake steamers, and it turned over the management of the two boats to one Albert Hutchinson, as confirmed by the 1932-33 Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Why is this significant? The fact is that Albert L. Hutchinson was for a great many years associated with the Hall Corporation, and he was president of that company for a lengthy period before his death in 1951. As a result, during his short period of management of GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER, the two ships operated as part of the Hall Corporation fleet and even were repainted with the traditional Hall stack design, black with a large white "wishbone" and letter 'H'. There has been much controversy about this stage in the careers of both vessels, but it appears that we have as much information as ever will be known about their management in this period, and it is our belief that neither ship ever was owned by Hall Corporation, nor did Hall itself ever charter or intend to buy either steamer.

During the winter of 1932-1933. BROWN BEAVER was wintering at Toronto with a storage cargo of wheat destined for Toronto Elevators Ltd. She was laid up near the foot of Spadina Avenue, between the steamers RALPH BUDD and SARNIAN, when there occurred an event which made the local press and which very well could have developed into a major problem, even though it was contained in time. The following article appeared in one of the Toronto newspapers on Monday, December 19, 1932.

"Smoke, rising in a thin plume through a ventilator of the stokehold of the s.s. BROWN BEAVER late yesterday afternoon, led to investigations by watchmen which revealed a smoldering fire in the starboard coal hatch (bunker), brought fire department detachments and provided the firemen with a difficult task before the threat to the grain-laden ship and two other ships was extinguished.

It was about 1934 when the camera of J. H. Bascom caught BROWN BEAVER and CHIPPEWA in winter quarters in the York Street slip, Toronto.

"Captain W. E. McGillivray, residing on the ship, had just started taking ship soundings for the day when he espied the faint plume from the starboard ventilator. He called to watchman A. E. Fitzsimmons of the SARNIAN, lying alongside, and the two wrested the heavy hatch cover loose. As they slid it back, smoke billowed out.

"McGillivray attempted to climb into the hatchway in an effort to ascertain the exact spot where the fire was burning. He was forced out by fumes. The two men forced the cover back into place to keep oxygen from reaching the smoldering blaze and ran to the nearest telephone on the docks. Before they had reached the ship again, they could hear the fire reels on the way down Spadina Avenue, at the foot of which the ship lay.

"Two hose wagons and an aerial truck under District Chief Corbett and Platoon Chief Gunn were on the scene within a few minutes, stripped the hatch gratings and tarpaulin off and poured two streams of water into the coal bunker. The fire was subdued after the nozzles of the hoses had been forced deep into the coal piles to reach the outbreak.

"The BROWN BEAVER, lying in the slip between the RALPH BUDD and the SARNIAN, formed the centre of a perfect sandwich of grain-laden craft. Captain R.Bruce Angus, of Toronto, commodore of the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Navigation Corporation (sic), was on the SARNIAN when the blaze was discovered and directed the efforts to reach the blaze. Watchman Ward White, of the RALPH BUDD, also assisted the men from the other craft.

"The BROWN BEAVER is loaded with about 3.000 tons of wheat, and has about 70 tons of coal in her bunkers', Captain McGillivray stated afterwards. 'The fire had been making slow headway for perhaps several days without it being noticed. If it had ever got started in the wheat, it would have been a tough job to catch, and it might have caused serious damage to the SARNIAN and the BUDD also if it had not been seen in time."

This press report is very significant, for not only does it tell an interesting story, but it solves a date problem for us. Why was BROWN BEAVER wintering at Toronto with storage for Toronto Elevators when Hall Corporation boats almost never were seen at that facility? The reason is that it was late in the 1932 season when Beaver Industries Ltd. sold GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER to the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Company Ltd., Toronto, a firm which had been incorporated just that year, but whose principals had entered the shipping business in 1931 with the acquisition of SARNIAN, which was registered to an affiliated company, the Northland Steamship Company Ltd. In fact, the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Company Ltd. itself was the shipping subsidiary of Toronto Elevators Ltd., which had been formed in 1928 by James Norris, Sr., Gordon C. Leitch and Stuart Playfair (the latter being the brother of James Playfair of Midland).

Certain sources have indicated that it was not until 1933 that Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence acquired the two BEAVERs, but we now are certain that it must actually have been late in the 1932 season, for had the sale not already taken place (whether the actual paperwork had been done or not), it would not have been likely that BROWN BEAVER would have been laid up next to SARNIAN at Toronto at all when the fire occurred.

Incidentally, we should note at this point in our narrative that not only did Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence purchase GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER, and transfer their registry from Middlesbrough to Toronto, but in fact Toronto Elevators Ltd. chartered as well the entire remains of the former owner of the ships, the Mathews Steamship Company, from 1931 until the receivers sold the fleet to Capt. R. Scott Misener and associates late in 1933. Thus, for a short period, GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER were once again under the same management with their former fleetmates.

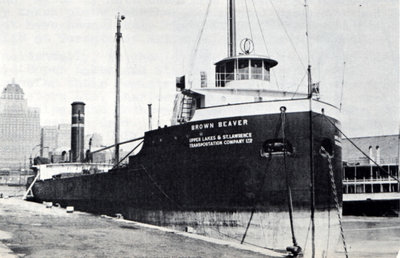

Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence painted the two BEAVERs black, with white forecastle rails and cabins. The company's name appeared in white letters arranged in two lines on the bows. The stack of each steamer was black with two narrow white bands (almost like the Mathews design), but the two white bands were separated by a band of green. By 1935, the funnel design was changed to green with a wide white band and a black smokeband at the top. Then, when the fleet was joined by the vessels formerly owned by James Playfair, after his death in 1937, Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence adopted the famous Playfair funnel colours, namely crimson with a wide black smokeband, which were given to the existing fleet at the beginning of the 1938 season. The white forecastle rail disappeared about the same time, following which the hulls were all black for a few years.

The company's name on the bows (but only of the BEAVERs) lasted until the early 1940s, when it was removed. After a few years' absence, the white forecastle rail (with black upper edging) returned, perhaps because someone in management realized that the ships looked far better with it. The white rail was retained by GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER, and indeed by most of the company's canallers, for the remainder of their careers, although this practice generally did not extend to the upper lakers in the fleet.

Many of the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Company's canallers were requisitioned for service on salt water during World War Two, and heavy losses were sustained as the little steamers fell victim both to enemy action and to the rigours of operation on the deep seas. However, both GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER remained in lake and river service, perhaps because of the fact that they were equipped with cargo booms (something of a rarity in the U.L.&St.L. fleet) and thus were far more suitable for the essential pulpwood trade than were most of the company's vessels.

It was during the war years, however, that GREY BEAVER suffered the first major accident of her career. One of the Toronto papers noted the 1941 incident under the headline "Toronto Ship Goes Aground, Crew Is Safe", with the subtitle "Feared S.S. GREY BEAVER Has Several Large Holes in Steel Bottom - Heavy Sea Prevents Rescue". The account of the incident followed.

"Houghton, Michigan, April 21 (1941) - The Canadian steamship GREY BEAVER, owned by the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Co., Toronto, was hard aground today on a reef two miles east of the Manitou Island Light in Lake Superior, off the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula. It was feared that the vessel has several large holes in her bottom. All on board were reported safe. Early efforts to remove the crew of 25 failed because of the heavy seas, which later moderated.

"The steamship, which is more than 250 feet long, went aground Sunday (April 20) for its entire length, its stern in nine feet of water. Coast Guards from the Eagle Harbor station got close enough to the vessel today to hear a shouted message from its skipper, Capt. (A. S.) Cavanaugh, for its owners.

The Coast Guard cutter TAHOMA was en route to the scene from Sault Ste. Marie, and was expected to arrive this afternoon."

GREY BEAVER remained impaled on her rocky perch for ten days. In fact, she was extremely lucky, for if it was true that she only had nine feet of water under her stern, then she was sitting right up on the rocks and the occurrence of any really heavy weather after the original stranding would virtually have ensured the loss of the ship. As it was, GREY BEAVER was successfully refloated on Wednesday, April 30, 1941, and she was towed to the shipyard at Port Arthur. There the necessary repairs were put in hand and GREY BEAVER was back in service that same season. Of course, the fact that so many canallers were away from the lakes in war service meant that GREY BEAVER had to be repaired in the shortest possible time.

GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER both survived the war years and, as far as we know, were not involved in any further accidents during that period. One change did affect them in the early 1950s, however, and that was the advent of radar as a navigation device on lake steamers. The benefits of radar had become quite obvious to all, and lake vessel operators began to fit the device in all of their ships. The canallers, however, had very little space in their small pilothouses, and many of them simply had no room for the placing of the then-bulky radar equipment.

Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence realized this fact and the company enlarged or completely reconstructed the pilothouses of most of its canallers to allow sufficient space for the equipment. GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER were so altered over the winter of 1952-53, with the front of the pilothouse being moved forward and the structure being lengthened by the width of one additional window on each side. This rebuilding meant that the front of the pilothouse overhung the forward bulkhead of the texas cabin, necessitating the forward extension of the bridge deck and the fitting of two longitudinal support struts to brace the structure. In fact, the change did not harm the appearance of either vessel, and actually rendered them rather distinctive, for none of their sisterships were treated in that particular manner.

Photo by J. H. Bascom shows BROWN BEAVER upbound above old Lock 20, west of Cornwall, on October 31, 1957.

GREY BEAVER suffered another major grounding on Tuesday, October 23rd, 1956, when she struck rocks in the American Narrows section of the Upper St. Lawrence River near Alexandria Bay, New York. The steamer remained fast on the rocks for about a week but finally was refloated and, after temporary repairs were made, she was taken to the drydock at Kingston for repairs.

In March of 1959, in anticipation of the many changes in the Canadian lake shipping scene that would be brought about by the opening that year of the new St. Lawrence Seaway, the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Company Ltd. was reorganized as Upper Lakes Shipping Ltd., Toronto. By this time, the fleet had already begun to dispose of some of its canallers, and several of them (notably SHELTON WEED, EDWIN T. DOUGLASS, GROVEDALE and PARKDALE) did not run after 1958. The 1959 season was the last for most of the Upper Lakes canallers in that company's service and many of them saw very little operation even in that year. GREY BEAVER was downbound in the Welland Canal on October 10, 1959, with storage grain for Toronto, and when she laid up at her home port the next day, it was thought that she would never run again.

It is October 10, 1959, and GREY BEAVER is downbound at Welland, just above the Main Street bridge. Photo by J. H. Bascom.

Nevertheless, although most of the Upper Lakes Shipping canallers had run their last, GREY BEAVER, BROWN BEAVER and the motorship BLUE RIVER, which were acknowledged to be the best of them, were not quite finished. Both BEAVERs were reactivated briefly during the summer of 1960, operating in the pulpwood trade to Thorold. GREY BEAVER, however, was laid up again at Toronto on July 7, 1960, while BROWN BEAVER went to the wall at the same port on July 20th. GREY BEAVER would never turn again, although BROWN BEAVER came out that autumn for one trip up the lakes to fetch a winter storage cargo for Toronto.

BROWN BEAVER was unexpectedly fitted out again briefly during 1961, and she made five trips to assist in the package freight trade which the company entered on what proved to be an unsuccessful basis. BROWN BEAVER soon returned to her lay-up berth at Toronto, but the fact that she ran at all in 1961 made her unique. That season, the company had altered its stack design by adding a white diamond with a black centre, which was placed on the dividing line between the crimson stack bottom and the black smokeband. BROWN BEAVER was given small diamonds for her stack when she fitted out for those five trips, and as such she became the only canaller ever to operate for Upper Lakes Shipping with the new funnel colours. She was also the last canaller ever to run for the firm, period!

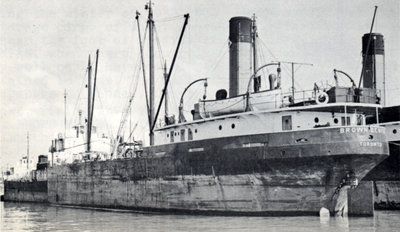

A September 17, 1961 photo by J. H. Bascom shows BROWN BEAVER, WITH U.L.S. diamonds on her stack, laid up in the Spadina, Avenue slip, Toronto.

Both GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER lay around Toronto Harbour thereafter, occasionally being loaded with storage grain but spending most of their time light, usually in the Spadina Avenue slip where many of the company's idle canallers lay. One by one, however, they were sold off, and although a few of them were operated briefly by other companies, most were sold for scrapping and disappeared from Toronto at the end of a towline, bound for the yard of a breaker.

On May 31, 1965, GREY BEAVER and BROWN BEAVER were both sold to Vic Loach and Harold J. Dixon, the latter being the former proprietor of the Toronto Dry Dock Company Ltd. These gentlemen contracted with a Toronto firm, Ship Repair & Supplies Ltd., to dismantle the steamers, and they were towed to the turning basin and moored on its north wall along Commissioners Street. There they were cut up and the sections lifted from the water, BROWN BEAVER being dismantled during the summer months and GREY BEAVER going under the torch during the autumn. The breakers made quick work of them and, by the beginning of 1966, nothing was left of either steamer except for the whistle of BROWN BEAVER, which was saved and incorporated into the extensive collection of steam whistles which, to this day, may be seen and heard in the Marine Museum of Upper Canada at Toronto.

Ed. Note: We would not have been able to present the newspaper reports incorporated into this narrative were it not for the scrapbooks kept by our late member and first treasurer, James M. Kidd.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.