Table of Contents

As readers of this journal will be aware, we spend much time in these pages examining the histories of the various canallers that were once so common on the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. We do this for two basic reasons, the first being that little has previously appeared in print in publications such as ours concerning these interesting little vessels, and the second being that, as a class of ship, they have almost completely disappeared from service. In fact, only two "pure" canallers (boats specifically built for canal service and still of canal dimensions) are still in regular operation on the lakes as self-propelled carriers, these being the motorships CONDARRELL, (a) D. C. EVEREST (81), and TROISDOC (III), (a) IROQUOIS (67).

Several other canallers still exist in one form or another on the lakes, however, albeit not looking much the way they did in their heyday. They survive as docks, barges, etc., and some of them have been lengthened and rebuilt to make them more viable for operation in today's economic conditions. One of these survivors, and one which is still relatively active and providing a useful service to her present owner, is the former Canada Steamship Lines bulk canaller MAPLEHEATH. Now into her seventh decade of operation, she is probably better suited to her present service than she was to her bulk trades during the last few years of her duties in C.S.L. colours, for her age was then very noticeable and she would certainly have been replaced by newer tonnage had not the prospect of the completion of the St. Lawrence Seaway prompted her owner to "make do" with the hulls it had, rather than building new vessels of dimensions to match the small locks of the old canals.

In the early years of the present century, British shipyards were beginning to realize that a regular mint could be made by building new vessels of canal dimensions for operation by Canadian shipowners. Knowing that they had a good thing going for them, these yards soon began to experiment with canaller design and, if there was nothing that they could do about the size of the boats, they made up for it with some of the imaginative designs and power plants that they produced for a few of the canallers.

Over the period 1910-1912, the firm of Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson Ltd. built two experimental canallers on speculation, in the hope that they would be snapped up by an operator for lake service. They were christened TOILER and CALGARY, TOILER having been, as might be imagined from her rather unusual name (with a bit of a sales pitch built right into it), the first of the two to be completed. TOILER was Hull 840 of Swan Hunter's Newcastle-on-Tyne yard, and was ready for service in 1911.

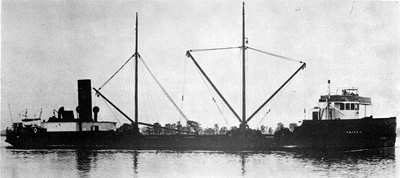

TOILER is seen in the St. Clair River in this 1915 Pesha photo, which shows her after her conversion to steam power.

The new vessel was 255.4 feet in length, 42.5 feet in the beam, and 17.3 feet in depth, with tonnages of 1693 Gross and 1036 Net. She was powered by a most unusual power plant for that day, consisting of two four-cylinder reversible diesel engines of the two-cycle type. Each engine was rated at 180 brake horsepower and each drove its own individual screw. In fact, TOILER was the first diesel-driven ship built in Great Britain, although the novelty of her construction is often ignored in favour of recognition of some of the larger early diesel vessels designed for deep-sea service.

If TOILER'S engines were unusual, so also was her appearance. In fact, the Lake Carriers' Association described her as the strangest-looking vessel to visit the lakes during 1911. Bluff-bowed, she had a full forecastle with a closed rail. Her anchors were sunk deep into round-topped pockets at spar deck level. She carried a rather large single-deck turret pilothouse, on top of which was the open navigation bridge, complete with awning and dodger. Behind the pilothouse was an ugly box-like texas, unadorned by any overhang whatsoever. Perhaps the most peculiar feature of her forward end, however, was the unsightly stovepipe which rose out of the starboard side of the forecastle deck, angled backwards at about 45 degrees, and then rose upward over the monkey's island just forward of the starboard bridgewing. As unusual as it may seem, TOILER carried her galley in the forecastle rather than in the after cabin, and this pipe was the galley stove vent. It really was not so much different from some of the bowthruster exhaust pipes carried today by lakers, those of JOHN A. FRANCE and J.N. McWATTERS coming readily to mind as being just as unsightly.

Two heavy masts were carried, spaced at roughly equidistant points down the spar deck between the forecastle and quarterdeck. Each mast was equipped with two cargo booms, one being slung forward of the mast and one aft. Apart from these masts, which were really nothing more than overgrown kingposts, no "regular" spars were carried by either TOILER or CALGARY.

Each ship was given a half-raised quarterdeck and so each sported a rather heavy counter stern, as the stern plating rose straight upward from the level of the spar deck until it met the open quarterdeck rail. The two lifeboats were carried atop the open after deck, one on each side. A very short and spindly stack, almost totally without rake, rose from the boat deck to vent the diesels, this stack topped by a small double-roll cowl. The stack rose just abaft a small "boilerhouse" or raised bunker hatch which actually sat on the spar deck rather than on the quarterdeck.

TOILER and her later sister CALGARY were nearly identical in appearance, the only major differences being that CALGARY had a longer section of open rail on her forecastle and her galley stovepipe rose just abaft the after bulkhead of the texas. CALGARY'S hatches also had higher coamings than did those of TOILER.

TOILER, duly completed by Swan Hunter and registered in her builder's name as Br.129767, successfully crossed the Atlantic on her maiden voyage and arrived at Montreal on September 21, 1911. She had been chartered from Swan Hunter by James Richardson and Company of Kingston, which intended to operate her in the grain trade. Richardson actually purchased TOILER outright in 1912 and, at that time, the management of the ship was taken over by James Playfair of Midland, Ontario.

TOILER was, however, not what one might have called a resounding success with her unusual engines. We have no reports of major difficulties, but we can well imagine the problems that would have resulted when repairs were necessary or when new parts had to be obtained. TOILER stranded in the St. Lawrence near Cardinal, Ontario, on May 24, 1912; she was salvaged and towed to Kingston where, during the winter of 1912-13. she was rebuilt. Richardson and Playfair took this convenient opportunity to remove her peculiar machinery and replace it with more conventional power.

The engine chosen for the rebuilt TOILER was a fore-and-aft compound steam engine, with cylinders of 27 and 44 inches and a stroke of 42 inches, which had been built in 1882 at Detroit by the Dry Dock Engine Works for the steamer D. C. WHITNEY, (b) GARGANTUA. The engine became available when this latter vessel was reduced to a barge in 1912. Steam was supplied by two coal-fired Scotch boilers, which measured 12 feet by 10 feet, and which had been built for another hull in 1889 by Alley and McLellan at Glasgow, Scotland.

The appearance of TOILER was considerably improved during the course of this reconstruction, for her boilerhouse was much enlarged to provide coal bunker facilities. As well, she was given a much larger stack, of medium height but quite thick and with just a hint of rake, and this gave her a much mo re balanced profile. It should be noted that CALGARY was never given such a rebuild until 1921 and remained a motorship throughout her short career on the lakes. She was sold for use on the east coast during the First World War and was renamed (b) BACOI. She never returned to the lakes but rather continued her coastal trading as a tanker for many years, at least into the 1940s.

In 1914, the ownership of TOILER was officially transferred to James Playfair's Great Lakes Transportation Company Ltd. of Midland, Ontario, although it seems unlikely that this change altered her duties to any significant degree. She carried the usual Playfair stack colours, crimson with a wide black smokeband, but her hull seems to have been black at all times and was never painted grey as were many of Playfair's boats over the years.

TOILER's career in Playfair's service was to be relatively short, however, for she was sold in 1916 for the sum of $90,706.00 to the Ontario Transportation and Pulp Company Ltd. of Thorold, one of the forerunners of what we now know as the Quebec and Ontario Transportation Company Ltd. It would seem likely that the O.T.& P.Co. acquired TOILER specifically to carry pulpwood from the St. Lawrence River ports to its paper plant at Thorold. We do know that, for a while, TOILER lost her heavy masts and this would seem only natural, as they would have severely complicated the carriage of deckloads of pulpwood. For this period of her career, TOILER was given a new foremast, a light pole which, without any rake at all, rose just abaft the break of the forecastle and carried a short, light boom. The new mainmast, a slightly heavier pole, was stepped well aft of the stack and, peculiarly, was heavily raked .

Two years later, in 1918, TOILER was purchased for $350,000.00 by Canada Steamship Lines Ltd., Montreal. The difference between the selling price of the steamer in 1916 and that in 1918, which was almost four times greater, would seem to have been the result of the effect of the First World War on the availability of serviceable canal-sized vessels. Many canallers had been sent to salt water for coastal or deep-sea service during the hostilities and a great number of them were lost abroad, with the result that fleets such as C.S.L. found themselves desperately short of good tonnage with which to handle their cargo commitments during the boom years that followed the war.

TOILER was soon painted up in C.S.L. livery and, in 1919, she was renamed b) MAPLEHEATH. For a few years, C.S.L. embarked on a program of giving newly-acquired vessels names beginning with the prefix "Maple", a symbol of their Canadian ownership. The last section of such names always began with a particular letter chosen to designate the type of ship involved; in MAPLEHEATH's case, the 'H' designated that she was a steel-hulled bulk carrier of canal size. We are not certain when MAPLEHEATH was brought into Canadian registry, but it may well have been at this time. Like most other British-built canallers, she retained her British registry for a number of years but eventually was placed on the Canadian register, this change being a rather simple one to accomplish.

On December 8, 1920, there occurred the sort of embarrassing accident which shipmasters and owners would just as soon avoid, but which occurs every so often and which has a marked humbling effect on those involved. For reasons now unknown, but perhaps in an attempt to accomplish an emergency stop so as to avoid striking a lock gate, she dropped her anchor whilst in the St. Gabriel Lock of the old Lachine Canal. She ran over the anchor and, with very little water between her bottom and the floor of the lock, she holed herself and sank right there in the lock. Salvage efforts were immediately instituted to avoid any lengthy blockade of the canal and MAPLEHEATH was refloated on December 9. Her coal cargo was unloaded and she was towed to Kingston and put into winter quarters. The necessary repairs were attended to during the winter months at the Kingston shipyard.

MAPLEHEATH operated for C.S.L. throughout the remainder of the 1920s without any further accidents of a serious nature but, as the decade came to a close, it was realized that the second-hand engine placed in the boat back in the Richardson/Playfair years was nearing the end of its usefulness, being then almost fifty years of age. Accordingly, she was repowered again in 1929. The fore-and-aft compound engine was removed and in its place was fitted a triple expansion engine, with cylinders of 17, 28 and 46 inches and a stroke of 33 inches, which had been built back in 1903 by the Polson Iron Works Ltd. at Toronto for the wooden steamer SIMLA of the Calvin Company Ltd., Garden Island. By 1929, SIMLA had long since outlived her usefulness to the C.S.L. fleet, to which she had made her way from Calvin ownership via the Montreal Transportation Company Ltd., which was formally bought out by C.S.L. late in 1920. The engine had been removed from SIMLA for further use and the old wooden hull had then been cast aside to rot away in Portsmouth harbour, just a small part of the extensive "boneyard" which accumulated there. The placing of the engine into MAPLEHEATH was done at the Kingston shipyard.

MAPLEHEATH had, by this time, been given back her heavy spar deck masts, although she no longer carried cargo booms on them on a regular basis. Her stack had grown considerably in height, probably at the time that SIMLA's engine was placed in her. And much improvement forward had been effected by the fitting of a small wooden upper pilothouse, of much the same type as were those added to the turret pilothouses of the first group of Eastern Steamship Company Ltd. canallers in the mid-1920s. These various changes had combined to make MAPLEHEATH appear less of an "oddball" than she had at any previous time in her life, although she still retained certain peculiarities, such as her complete lack of deck sheer and her rather "bald" stern, with its only above-decks cabin being the boilerhouse.

MAPLEHEATH saw some service during the 1930s, although she did spend much time in lay-up at Kingston and elsewhere due to the poor business conditions which then prevailed. MAPLEHEATH did, however, possess a greater cubic capacity for cargo than did many of the C.S.L. canallers and she ran a good deal more than did most of them. With the Great Depression past by the late 1930s, she resumed regular service, whereas some of the older canallers in the fleet did not and eventually found their way to the breakers' yards.

In 1947, MAPLEHEATH was once again taken to the shipyard at Kingston for another extensive rebuild. Her old, second-hand boilers, almost sixty years of age, were removed and replaced by two new single-ended Scotch boilers, 16.6 feet by 12.6 feet, which had been built in 1941 by the John Inglis Company Ltd., Toronto, probably for a corvette. Her heavy masts were once again removed and this time they were replaced by light pipe masts, the fore stepped just abaft the forward cabin and the main just forward of the stack. She was also given a new pilothouse which was placed atop the old lower turret. The new cabin was, surprisingly, built of wood and looked much like the old upper house, except that it was somewhat larger and had seven windows across its curved front.

MAPLEHEATH is inbound at the Toronto Eastern Gap with a deckload of autos in this July 1951 photo by J. H. Bascom.

Thus refurbished, MAPLEHEATH returned to service to do battle with a changing economy, one which was rapidly rendering such boats unprofitable to operate. With the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway progressing during the 1950s, and with newer canallers handling more of C.S.L.'s cargo requirements, some of the steam canallers were relegated to spending more and more of their time in ordinary, but MAPLEHEATH's high cubic capacity meant that she did run regularly, for a certain number of the older boats had to be kept in service until the new canals could be opened and the upper lakers run straight down to the river ports without trans-shipment of their cargoes.

MAPLEHEATH underwent only one other change that we know of during this period, and that entailed the long-overdue removal of the ugly galley vent pipe from the starboard side of the forecastle. We have no idea whether the galley itself was relocated, or whether another method of venting galley heat and fumes was found, but the pipe disappeared at last. This change might also have come about as a result of the fitting of more modern electric ranges in the galley to replace older cookstoves.

MAPLEHEATH was not a canaller that was regularly seen in Toronto Harbour, for she normally stayed in the grain trade. But, during the 1950s, she was used to carry almost anything that needed carrying. As a result, she appeared at Toronto several times carrying automobiles and, on at least one occasion in 1958, she brought in a load of pipe sections (including a high load) to be used in pipeline construction.

Crews were, by this time, becoming more accustomed to the better accommodations available in more modern lakers, however, and MAPLEHEATH was not a popular ship amongst crewmen. With her total lack of sheer and her small freeboard when loaded down to her marks, she was a notoriously "wet" boat and regularly shovelled lake water over her decks in heavy weather. Particularly in her stern quarters, the water would get down into the cabins and remain there, much to the chagrin of the occupants.

With the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, however, the usefulness of MAPLEHEATH to C.S.L. was at an end and, of course, nobody else was in the market for a steam-powered canaller of her age. She spent the 1959 season in idleness at Kingston, laid up alongside the Cataraqui Elevator, a spot long favoured by C.S.L. for the storage of surplus vessel tonnage. She would, no doubt, soon have been sold for scrapping as were other idle canallers, but instead she managed to find for herself a much more rewarding future.

On November 29, 1959, MAPLEHEATH was purchased by the McAllister Towing Company Ltd., Montreal, (now known as McAllister Towing and Salvage Ltd.), and was reduced to a crane-equipped salvage barge and lighter. Her after end remained much as it had been, complete with funnel, but the forward cabins were cut away. A large crane was placed on deck for the lifting of cargo from stranded ships. Painted up in the same colours as McAllister's Montreal harbour and wrecking tugs, complete with the bright yellow stripe around her hull, MAPLEHEATH remains active in the McAllister fleet to this day, and she is frequently called upon to assist vessels in distress in the lower lakes area or on the St. Lawrence River. It is anticipated that there will be a need for her as a wrecker for many years to come and, provided that she is kept in reasonable condition, there seems to be no reason why MAPLEHEATH should not still be active well into the future.

(Ed. Note: For his assistance with the researching of the history of MAPLEHEATH, our thanks go to our chief purser, James M. Kidd.)

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.