Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| Lake Huron Lore | |

| Memories of a Day at the Welland Canal | |

|

Ship of the Month No. 66 KINGSTON | |

| Table of Illustrations |

No discussion of the relative aesthetic merits of various ships is complete without mention of certain names, particularly some of the nightboats which frequented North American waters during the early years of this century. Included would surely be CITY OF DETROIT III, CITY OF CLEVELAND III and SEEANDBEE and, from salt water, the famous Fall River steamers PLYMOUTH, PROVIDENCE, PRISCILLA and COMMONWEALTH and the Los Angeles Steamship Company's beautiful propellors HARVARD and YALE. But another ship is usually included in this exalted group, a ship which, although not nearly as large as the most famous of the nightboats, may well rank as one of the most handsome steamers of her type ever built. She was Lake Ontario's own KINGSTON, a paddler that served our area for nearly half a century.

The passenger trade between Toronto and Montreal, the two largest cities of the Dominion of Canada, was perhaps the first major domestic route on the Great Lakes. Down through the years, the Montreal-Toronto trade catered to vacationers and business travellers alike and the route prospered, although steamers running between the two cities had either to run or bypass the rapids of the St. Lawrence River. It was a fact of life that only small steamers could transit the old St. Lawrence canals and such transits were often lengthy when the locks were jammed with traffic. The way around such problems was to operate one set of vessels from Toronto to the head of the canals and another set of ships down the rapids to Montreal and back up through the canals.

By the latter part of the nineteenth century, the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company Ltd., which had come to be the major operator of passenger vessels in the Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River areas, had gained supremacy and, in fact, a virtual monopoly on the Toronto-Montreal route. By changing from ship to ship within the R & O fleet, a traveller from Ontario could make his way by boat all the way to Quebec City and, via the Niagara Navigation Company Ltd. (later acquired by R & O), the chain was extended so that connections through to salt water could be made from Niagara and from the Buffalo area. This connecting service prompted the Richelieu and Ontario to use as its motto the catch-phrase "Niagara to the Sea".

The boats operated by the R & O on the Toronto to Prescott service, the upper half of the run to Montreal, were by the end of the nineteenth century in need of replacement and so in the closing years of the century, R & O retained the services of one Arendt Angstrom to design for the company first one and then a second new overnight steamer, Angstrom later became the chief naval architect for the Canadian Shipbuilding Company Ltd. and was eventually destined to become general manager of that firm. Angstrom was a most competent marine architect, his work showing signs of the influence of the great Frank E. Kirby.

By this time, the nightboat was becoming a hybrid beast. Day steamers and excursion boats didn't change all that much in those years but the nightboat was the cream of all passenger vessels. It was the nightboat that whisked businessmen and vacationers alike to their destinations while they slept and the boats were built not only for speed and comfort but also, as the years passed, to show the flag for their owners. As a result, they became more fancy and luxurious, the steamers growing larger and their interiors becoming less and less those of steamboats and more and more those of classical buildings. Some of these palace steamers were successful while others were something less than successful in design, their cost outweighing their usefulness and their interior design being so heavy and pretentious as to be almost grotesque.

The first of Angstrom's boats for the R & O was built in 1899 by the Bertram Engine Works at Toronto and was christened in honour of the city in which she was built. TORONTO was an instant success and outshone any other steamer then operating on Lake Ontario. As a result, when R & O wanted a second vessel to serve as a running-mate for TORONTO on the Toronto to Prescott overnight service, the firm had no hesitation in seeking the services of Mr. Angstrom to produce an even better boat than the 269-foot TORONTO.

The new steamer, like TORONTO, was a steel-hulled sidewheeler and was built by the Bertram Engine Works at Toronto as the company's Hull 37. She was 288.0 feet in length, 36.2 feet in the beam (65.0 feet over the guards) and 13.3 feet in depth. Her Gross Tonnage was 2925 and her Net was 1909. The new steamer's registry was opened at Toronto and she was given official number C.111654. She was named KINGSTON in honour of the eastern Lake Ontario port.

KINGSTON was powered by a direct-acting, inclined, triple-expansion engine which had cylinders of 28, 44 and 74 inches and a stroke of 72 inches. Steam was supplied by four coal-fired Scotch marine boilers measuring 11 by 11 1/2 feet, the boilers and engine having been built for the ship by Bertram's. The machinery produced 461 Nominal Horsepower and drove the two relatively small feathering sidewheels which were housed in well-decorated but rather unobtrusive paddleboxes which rose just above the level of the cabin deck.

Angstrom gave KINGSTON a superlative interior decor. Her staterooms, accommodating 365 passengers, were located on the upper two decks and the bulkheads were covered with beautifully-carved designs. The cabin was divided into two sections by the funnel casing, the forward and main saloons both being galleried structures. The forward saloon, the smaller of the two, was given an intricately carved ceiling, the centre part of which was a glass skylight which flooded the area with daylight. The bulkhead of the funnel casing displayed a typical classical mural and the surprisingly plain stairway was set off by a selection of potted ferns. The railing around the well in the upper deck was a masterpiece of Victorian elegance.

The main saloon was the pride of the ship and featured a staircase of Corinthian inspiration. The ceiling contained a centre panel dominated by hexagonal and triangular designs and light was admitted to the cabin by a clerestory running the entire length of the saloon as well as the area occupied amidships by the boiler uptakes. The main companionway led down to another which took passengers to the main deck.

Just as Frank E. Kirby's masterpieces of marine architecture (such as CITY OF DETROIT III) were dominated by their superb pilothouses, so did Arendt Angstrom have a hand for designing this feature of a steamboat. Both TORONTO and KINGSTON had extremely fine pilothouses, not cluttered by a sunvisor, and featuring a protruding roof-edge and four-sectioned windows which dropped to provide ventilation. As was typical of steamboats of the day, both ships carried across the front of the pilothouse a finely-lettered nameboard which, unfortunately, was frequently obscured from view by the large canvas dodger which could be stretched on the bridge deck rail.

KINGSTON entered service with an all-white hull and white cabins, her two well-proportioned but barely raked stacks bearing the usual Richelieu and Ontario colours of red with a black smokeband. Although she was to lose them in later years, she originally sported gold-leaf dragons of quite ferocious appearance on her trailboards. As built, KINGSTON carried only one mast which sprouted from the texas cabin immediately aft of the pilothouse but after she was in service for a short period of time, she was given a rather flimsy mainmast located just abaft the paddleboxes. The after mast was added incompliance with government regulations requiring the carriage of a stern running light. The foremast was originally fitted with a prominent gaff.

KINGSTON, of course, differed from TORONTO in that she was somewhat longer, a difference in size which was certainly noticeable, but she differed in certain other basic ways as well. The most obvious, perhaps, lay in the fact that KINGSTON was given two stacks while TORONTO carried only one. KINGSTON carried on the bow, just ahead of the cabin structure, two rather prominent ventilators with cowls, a feature that TORONTO lacked entirely. And KINGSTON was built with her dining saloon forward on the main deck, its location indicated by a long row of large windows. TORONTO, on the other hand, was built with her dining saloon in an unusual location forward on the upper cabin deck, an arrangement that was obviously less than satisfactory as the facility was soon moved down to the main deck forward.

KINGSTON joined TORONTO on the Toronto-Prescott overnight run and was an even greater success than the earlier ship. The vessels sailed from Toronto on alternate days during the summer months (the service was rather less frequent during the off-season), departing from their home port at about 2:30 p.m. Stops were scheduled at Charlotte, Kingston, Alexandria Bay and Brockville with the arrival at Prescott timed so that those wishing to proceed to Montreal could transfer to the dayboats operating on the rapids for the scenic run down to Montreal.

KINGSTON operated dependably and very seldom made the news, this being the result of the fact that she got herself into very few scrapes during her lifetime. The most notable feature of her operation was her regularity and the unspectacular nature of her service. But in 1908 she did make the news when she was in collision with the small American steamer TITANIA off Charlotte harbour at about 10:00 p.m. on August 11th. Both vessels were attempting to enter the piers and neither signalled nor gave way to the other. The U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service later held an enquiry at Buffalo and both ships were held to be at fault for proceeding at speeds unsuitable for harbour waters and for not signalling to each other. TITANIA's master lost his license over the affair but the court, having no jurisdiction in Canada, could not touch the ticket of KINGSTON's master.

The "teens" saw KINGSTON under the command of Capt. E. A. Booth who sailed the ship for many years. It was with Capt. Booth on the bridge that the boat went through the only change of ownership that she was ever to see, that occurring in 1913. But 1913 was also a notable year for KINGSTON for another reason. The R & O, through an American subsidiary, the Richelieu and Ontario Navigation Company of the United States, was operating its steamer ROCHESTER on Lake Ontario from Toronto to the American side and it was believed that it was no longer necessary for KINGSTON and TORONTO to make the Charlotte call. Accordingly, the Toronto sailing was rescheduled for 6:00 p.m., it being thought that such a departure time would be more suitable for passengers arriving by train. By the following year, however, ROCHESTER was gone from the Toronto-Rochester route and TORONTO and KINGSTON resumed their Charlotte calls, their Toronto departure being scheduled again for mid-afternoon.

The year 1913 brought the formation of Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. of Montreal, the R & O being the major firm participating in the mergers which led to the birth of what was first called the Canada Transportation Company Ltd. but was soon rechristened as Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. TORONTO and KINGSTON were placed in what was known as the Western Division of C.S.L.'s passenger operations and in due course were given the familiar red, white and black stack colours. In latter years under R & O ownership, the boats had been given black hulls and under C.S.L. management they carried at various times black, white and green hulls.

During the spring of 1916, TORONTO was drydocked at Kingston and refurbished, and when she emerged she sported a wireless antenna strung between her masts, a feature that was soon added to KINGSTON as well. KINGSTON'S wireless call sign was VGMD, her wireless equipment being carried in a small cabin aft of the second funnel. It was thought that the wireless would allow passengers to keep up to date on news stories of the day, especially those concerning the progress of the war in Europe. As well, each boat received "moving picture apparatus for the amusement and instruction of passengers".

By 1920, Capt. Booth had moved over to TORONTO and KINGSTON was commanded by Capt. A. E. Stinson. The twenties were good years for the boats and they continued to operate a daily service during the summer months, the frequency being cut back to thrice-weekly during the off-season. They were able to maintain this service right through the Great Depression as well, their route not being affected by the poor business conditions to the point where a reduction in frequency of sailings would have been necessary.

It was as things were improving again after the Depression that KINGSTON was involved in one of her few serious accidents. The year was 1936 and the ship was approaching the dock at Brockville one day when she suffered a mechanical failure. The engine failed to reverse and KINGSTON struck the dock hard. As she glanced along the wharf, she canted over to starboard and her port wheel literally "walked" along the dock until her bow struck the shore. Needless to say, rather severe damage was occasioned to both the wharf and the ship but repairs to both were put in hand.

Strangely enough, the end of the Depression also meant the end for TORONTO, although business conditions had nothing to do with her demise. As a result of the disastrous fire which in September 1934 destroyed the Ward Line coastal steamer MORRO CASTLE with substantial loss of life, the U.S. government in 1938 instituted regulations which, amongst other requirements, prohibited the operation in U.S. waters of passenger steamboats having a wooden main deck. Unfortunately, TORONTO was so afflicted although KINGSTON had a steel main deck, and since the vessels' route took them to two American ports, TORONTO could not continue. She was laid up in the Turning Basin at Toronto and in due course was given a coat of grey paint to help preserve her woodwork against the day when she might once more be used by the company on some other route. That day, however, never came and on June 14, 1947, TORONTO was towed to Hamilton by the tug HELENA, the veteran paddler having been sold to the Steel Company of Canada Ltd. for scrapping. After the retirement of her running-mate, KINGSTON carried on the Toronto-Prescott route alone.

Another serious accident involving KINGSTON occurred on June 17, 1941 when she grounded on a shoal in the St. Lawrence. The Pyke Salvage Company sent its tugs SALVAGE PRINCE and SALVAGE QUEEN to her aid and KINGSTON, after a week on the shoal, was freed with the assistance of pontoons. Shortly after the steamer had floated free but before she could be moved from the scene, she was a victim of a thunderstorm in which lightning struck her foremast. Whether the lightning decapitated the mast or whether its top was lopped off by repairmen afterwards we are not certain, but the mast was considerably shorter when the steamer re-entered service. It is said that KINGSTON'S longtime master, Capt. Benson A. Bongard, was so shaken by the accident that the company had to bring Capt. H. W. Webster of the CAYUGA to the scene to replace Capt. Bongard for the trip to the Kingston drydock. Capt. Webster would eventually replace Capt. Bongard on a permanent basis and, in fact, he was destined to be KINGSTON's last master.

KINGSTON carried on by herself through the war years and, in fact, all the way to the end of the decade. She was getting on in years but the service was popular and it looked as if the paddler would keep going for a good many more years. In fact, her engine was rebuilt in 1948, hardly the sort of work likely to be done by an owner considering the retirement of a vessel. But as KINGSTON's 1949 season was drawing to a close, there occurred an event which was to prove to be the undoing of the veteran steamer.

During the early morning hours of Saturday, September 17, 1949, the C.S.L. upper lake passenger and package freight steamer NORONIC was lying on the west side of Toronto's Yonge Street passenger terminal, the ship being on a post-season cruise with a large complement of Americans on board. Fire broke out on the ship and by morning, NORONIC was a sunken, burned-out wreck, the lives of many of her passengers having been snuffed out during the holocaust. At 2:40 p.m. that afternoon, KINGSTON sailed from Toronto on her last scheduled run of the season, a trip that was to prove to be her very last.

KINGSTON, once her final round trip had been completed, went to the shipyard at Kingston where she was scheduled to undergo considerable maintenance work during the winter. In fact, much work was actually done on her but before it could be finished, the Canadian government in January 1950 dropped a bombshell in the form of comprehensive and stringent new fire regulations which were a direct result of the NORONIC disaster. In order to bring KINGSTON into compliance with the new requirements, C.S.L. would have had to spend approximately $600,000 to install fire alarms, sprinkler systems and additional bulkheads. As might have been expected, the company was unwilling to expend so great a sum on a boat of KINGSTON's age and accordingly it was immediately announced that the Toronto-Montreal passenger service would not be operated in 1950, the KINGSTON being retired from her Toronto-Prescott run and RAPIDS PRINCE from her connecting service between Prescott and Montreal.

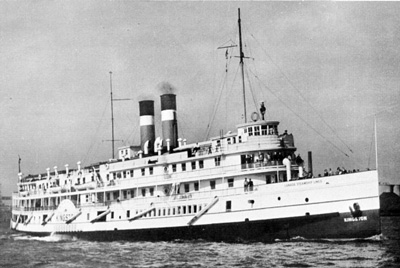

This may well be the last photo taken of KINGSTON while in operation From the camera of J. H. Bascom, it shows her leaving Toronto on her lat trip, September 17, 1949.

As it was obvious that KINGSTON would never operate again, C.S.L. wasted no time in disposing of the steamer. During the spring, she was towed to Hamilton and there the wreckers began to rip into her beautiful woodwork. By early summer, there was not much left except the hull and the funnel casing at the top of which forlornly perched her two stacks. The hull was then towed around to the yard of the Steel Company of Canada Ltd. where it was cut up.

KINGSTON lasted a good deal longer than most of the famous nightboats and, had it not been for the events of that fateful September 17th, the chances were very good that she would have operated yet a few years more. Nevertheless, KINGSTON had gained a place in the hearts of the Lake Ontario travelling public and will long be remembered by local residents as well as by the marine historians who so admired her grace and elegance.

KINGSTON may have left another legacy too, but one that is not recognized as such by the many people who come in contact with it. It is said that Thousand Island salad dressing was invented in the galley of KINGSTON by a steward who had run out of other dressing and who was faced by a dining saloon full of hungry travellers. This may or may not have been the case, but either way, KINGSTON was worthy of recognition and deserved to be remembered for many, many years.

Previous

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.