Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Marine News | |

| The James Photographs | |

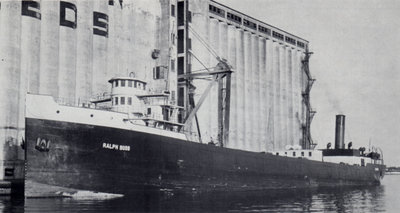

| Ship of the Month No. 157 Ralph Budd | |

| Dundurn Revisited | |

| Additional Marine News | |

| Table of Illustrations |

As a change of pace this issue, we decided to feature the story of one of the many distinctive American upper lake package freighters which at one time were such a very familiar sight in so many ports. As well, this particular steamer was for a number of years a member of the "great white fleet" of the Great Lakes Transit Corporation, upon the scheduled passage of whose beautiful vessels it was often said that watches might be set.

Our steamer was a steel-hulled, 'tween-deck package freighter, which was built as Hull 7 of the Great Lakes Engineering Works yard at Ecorse, Michigan. Constructed to the order of the Western Transit Company, which was the lake shipping subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad, she was launched on Saturday, June 10, 1905, and was christened SUPERIOR. It was the custom of her owner to name its ships for the ports which the line served, this steamer's name honouring the city of Superior, Wisconsin. SUPERIOR was enrolled at Buffalo, New York, as U.S.202329.

SUPERIOR was 381.0 feet in length, 50.2 feet in the beam, and 30.2 feet in depth, with tonnage of 4544 Gross and 3845 Net. The package freighters of the various railroad-affiliated lines were required to move their freight on tight schedules set for their movements, and so they were given far more power than most other ships of their size. SUPERIOR was fitted with a big quadruple-expansion engine built for her by the shipyard. It had cylinders of 20 3/4, 30, 43 1/2 and 63 inches, and a stroke of 42 inches, and was capable of producing 1,800 I.H.P. Steam at 160 p.s.i. was produced by two coal-fired Scotch boilers which measured 14 3/4 feet by 12 feet. Beeson's directory indicated that the boilers were manufactured by Hoffman & Billings, Milwaukee, while the American Bureau of Shipping recorded the boilermakers as the Marine Boiler Works. We cannot say for certain, but we suspect that these are simply two different methods of describing the same boiler shop.

Late-season young photo caught SUPERIOR downbound at the Soo in 1913. Note JAMES A. FARRELL in background.

Like most of the other upper lake package freighters owned by the railroads, SUPERIOR was not just a fast and efficient carrier, but she also was an extremely handsome ship. She had just the right amount of sheer to her hull, with a straight stem and a graceful counter stern with considerable overhang. In fact, she was all of 402'6" in overall length, and she was amongst the largest of the railroad boats, only a few of them exceeding her in dimensions. She had a full 'tween deck in the hull for additional cargo stowage, with access to the holds provided through six large cargo ports set in each side of the ship, as well as through deck hatches. There also were hatches in the 'tween deck for access to the lower holds.

There was a full raised forecastle, which was protected by a short closed rail at the bow, with an open rail around the rest of the forecastle head. A section of closed rail ran back down the spar deck as far as the large squarish texas cabin, which was set back off the forecastle and abaft the first hatch. The pilothouse, a rounded structure with five big windows in its front, sat atop the texas and just in front of a thwartship cabin which contained the master's quarters and office. Atop the pilothouse was an open bridge, from which the steamer usually was navigated. There were two sets of bridgewings, one set on the same level as the open bridge, and the other placed slightly aft and lower, being the protruding roof of the upper accommodations cabin. A large and elaborate nameboard ran around the front of the pilothouse below the windows. A tall, heavy and well-raked foremast rose from the deck just abaft the forward cabins.

An open rail ran back most of the way down the spar deck, giving way to another section of closed rail beside the after cabin and around the fantail. The after house itself was a big structure, sporting large windows. At its forward end was a prominent, indented boilerhouse (which later was equipped with a high bulwark enclosing the coal bunker hatch). The mainmast rose out of the deck just forward of the boilerhouse. The funnel, tall, well-raked and fairly thin, sprouted from the slightly raised boilerhouse roof, and was surrounded by several large ventilator cowls. A lifeboat was set on each side of the upper deck aft, the boats being worked from radial davits. A clerestory over the after cabin admitted daylight to the messrooms.

On SUPERIOR'S spar deck, just forward of the boilerhouse, was a "doghouse" providing additional crew accommodations. At this stage, she had no deckhouse with cold space for perishable cargo. It was not until the early 1920s that the ship was fitted with her own refrigeration equipment on deck so that she could provide true reefer facilities.

SUPERIOR was painted in the unusual colours of the Western Transit Company, which made all of its vessels very distinctive. Our steamer wore a brown hull and forecastle, while her cabins and deckhouses were white. Her stack was black with a wide orange band, the funnel design being very similar to that carried to this day by the ships of the Interlake Steamship Company.

SUPERIOR operated on the various Western Transit routes from the ports of Lake Erie, and mainly Buffalo, to those of Lakes Michigan and Superior. General merchandise made up most of her cargoes but, like most of the package freighters, she would often bring cargoes of grain eastward in her lower holds. Another cargo which these vessels frequently carried was bagged flour.

In 1915, the United States government enacted a piece of legislation which was to have great impact on the lake shipping scene and which, seen in distant hindsight, may well have been the most important government involvement ever in lake shipping. That year saw the passage of the Panama Canal Act, one section of which made it unlawful for a U.S. railroad to operate lake shipping routes which parallelled its rail lines. There was little formal opposition to the legislation, except for that of the Lehigh Valley Railroad, which challenged the Act in the courts and, as might be supposed, eventually lost after a long and expensive fight.

The Interstate Commerce Commission insisted upon the railroads' divestiture of their shipping lines and so, on February 22, 1916, a new firm, the Great Lakes Transit Corporation, was formed to take over the ships formerly operated by the many railway-controlled fleets. Chairman of the Board of the G.L. T.C. was William James Conners of Buffalo, who had been associated with many of the railway lines at various times and who had operated a major stevedoring/freight-handling service for the railroad-operated fleets. Associated with him in G.L.T.C. were many of the executives of the various railroads involved, and the fact that the rail lines actually backed the formation of the new firm is indicated by the capitalization of the G.L.T.C. in the amount of $20 million, an extraordinary sum for 1916.

The Great Lakes Transit Corporation "inherited" a huge fleet of package freighters, including most of the vessels formerly operated by the railroads. Some of the less efficient carriers in the fleet were sold for salt water wartime service and were sent to the east coast in 1917, from which none of them returned to the fleet. All of the best steamers, however, were retained for the new company's various routes. Great Lakes Transit had a large number of possible colour schemes to choose from for its boats and, for better or for worse, it selected the colours previously worn by the Western Transit ships such as SUPERIOR. (The selection of these colours may also have had something to do with the prominent position occupied by the New York Central Railroad in the formation of the new company.) Thus, SUPERIOR retained her old colours, the only changes being the addition of the company's name and also its logo to the bows of the ship. The logo was made up of the intertwined letters 'G', 'L', 'T' and 'C'.

Nevertheless, these colours lasted only a decade, and the company finally made the move to a more pleasing colour scheme. In 1925, Great Lakes Transit adopted the colours formerly used by another of its antecedents, the Anchor Line, which had been operated by the Pennsylvania Railroad. As a result, SUPERIOR'S hull became white, with a high green boot-top. Her cabins remained white, while her stack was painted crimson with a wide black smokeband. These "new" colours greatly complemented the lines of SUPERIOR and her numerous near-sisters, and gave them even more of a yacht-like appearance. When seen racing along, with a great bow wave, and a plume of smoke trailing from the stack, very few other lakers could match their beauty and grace.

Meanwhile, in the early 1920s, the ship had been equipped with refrigeration equipment, whose installation added to the clutter on her spar deck. A large new deckhouse was added to house the cold space, and it was located between the bridge structure and the crew's "doghouse". The refrigeration equipment itself was located in a small house set just forward of the reefer cabin.

Along with the addition of the cooling equipment, another of the improvements which Great Lakes Transit added to SUPERIOR during the early 1920s was an enclosed upper pilothouse. It not only provided some much-needed comfort for the navigation officers during inclement weather, but it also added to the steamer's appearance, helping to balance her profile. The new pilothouse was roughly the same shape as the lower cabin, which it overhung a bit at the back, and in fashion typical of the package freighters, there was no walkway around the new house. Incidentally, we should note that, by this time, her tonnage had been increased to 4671 Gross and 3972 Net.

On September 22, 1924, SUPERIOR suffered fire damage to her cargo whilst out on Lake Superior off Duluth. The freight allegedly was damaged to the tune of some $20,000 which was not a figure to sneeze at by any means, but we know of no damage to the ship herself. Two years later, in 1926, SUPERIOR was renamed (b) RALPH BUDD, the practice of Great Lakes Transit being, at that point in time, to rename many of its steamers in honour of executives of the various railroads for which the fleet handled cargoes. Budd was also a designer of rail equipment. Buffalo remained the home port of the steamer despite the change of name.

The steamer had been a relatively lucky vessel until the mid-twenties, but then things began to happen to her. Not only was there the fire of 1924, but on Wednesday, September 7, 1927, she stranded in heavy weather on Pine River Reef in Lake Superior east of the Keweenaw Peninsula. However, she was quickly released and put back in service after undergoing the necessary repairs. But if RALPH BUDD's luck had begun to sour, the wheels fell off completely for her and for the entire Great Lakes Transit fleet in 1929, for in that season the BUDD became the first vessel ever to be lost out of the company's fleet since its formation thirteen years earlier. To make matters even worse, the same storm that caused her loss also wrecked another of the fleet's vessels, and a third stranded to a total loss later in the season.

On the evening of Tuesday, May 14, 1929. RALPH BUDD cleared Duluth under the command of Capt. D. McLeod. She was bound for the lower lakes with a combined cargo of grain, package freight and refrigerated cargo. The steamer encountered heavy weather and, on the evening of Wednesday, May 15, she was driven ashore on Saltese Point, one of the smaller points on the Keweenaw Peninsula near Eagle Harbor. The BUDD was stuck fast, but her entire crew of 31 was safely removed from the wreck by the efforts of the crew from the Eagle Harbor Coast Guard station. It was determined that the BUDD, which lay close inshore, down at the stern and with a sharp list to port, was very severely damaged, and accordingly she was abandoned to the underwriters on July 8, 1929.

RALPH BUDD is wrecked on the Keweenaw Peninsula in this 1929 photo.

Before we continue with the story of RALPH BUDD, we should pause for a moment to consider the other accidents which plagued the Great Lakes Transit fleet in 1929. On the very same day as the BUDD was wrecked, the company's steamer J. E. GORMAN, (a) NORTH LAKE (27), was upbound for Duluth, loaded with package freight and automobiles. Caught in the same severe storm, she lost both her rudder and propeller and, helpless, she was thrown ashore east of Marquette, Michigan, at Rock River. Her crew was rescued by the Marquette Coast Guard surfboat, and the GORMAN was floated free on May 19 by the tug GENERAL. She was taken under tow to Superior, where extensive repairs were put in hand.

Then, on October 22, 1929. the G.L.T.C. steamer CHICAGO, downbound from Duluth, encountered a severe gale and blizzard. She tried to shelter in the Portage Ship Canal but was unable to enter it, and was blown before the storm until she fetched up on the shoals close to the shore of Michipicoten Island. The crew got ashore in the lifeboats and then split up. Some walked to Quebec Harbour, where they reached safety and assistance on the 25th, while the rest were plucked from their camp site near the wreck on the same day. CHICAGO had stranded to a total loss and never was salvaged, although part of her valuable cargo was located and removed over the years. Her battered remains still lie in the waters near the island.

RALPH BUDD, however, was not as seriously injured as was CHICAGO, and late in the 1929 season, she was pulled from the rocks by the crews of the Reid Wrecking Company of Sarnia. Early in 1930, Reid, who had purchased the BUDD, resold her to Sin Mac Lines Ltd., Montreal, which immediately resold her to James Playfair of Midland, Ontario. Perhaps it would be more proper to call the transaction a transfer rather than a sale, since Playfair had been one of the principals of Sin Mac since the mid-twenties.

In any event, Playfair had RALPH BUDD repaired and she was registered at Midland as C.154862, with no change in name. On the Dominion register, her tonnage was recorded as 4537 Gross, 3350 Net. She was placed under the ownership of the Great Lakes Transit Corporation Ltd., Midland. This was a new Playfair company, whose name seems to have been chosen so that as little repainting of the ship would be required as possible. Only a minor change in the corporate name as it appeared on the forecastle was required, and she retained her white hull and green boot-top. Her stack needed no repainting at all, as Playfair for many years had used the same crimson and black funnel colours as had Great Lakes Transit in the United States. RALPH BUDD was finally given one coat of grey hull paint about 1935, her forecastle remaining white. This belated alteration brought the ship more in line with usual Playfair livery.

RALPH BUDD is in Playfair colours at Toronto Elevators. Photo c. 1932 by J. H. Bascom.

After several years, Midland Steamships Ltd., Midland, another of Playfair's ventures, took over the ownership of RALPH BUDD, as the entrepreneur consolidated what remained of his once-great shipping empire. The BUDD, despite her 'tween deck, which made the carriage of bulk cargoes difficult, ran mostly in the grain trade. It must be remembered, however, that those were the years of the Great Depression, and accordingly RALPH BUDD carried almost anything that required moving. Even loads of hay were not unknown to her. Still, as she was no longer carrying general merchandise on a regular basis, all of her refrigeration equipment was removed, together with all of the spar deck "doghouses", except for the one that contained crew quarters.

During 1937, however, James Playfair died and his holdings were dispersed. His lake ships were acquired by the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Company Ltd., Toronto, which was operated by Gordon C. Leitch and James Norris. The company was an outgrowth of Toronto Elevators Ltd., of which Leitch and Norris, along with James Playfair, had been founders back in the twenties. The BUDD's ownership was transferred to U.L.&St.L.T.Co., and she was given a black hull and white forecastle, while her cabins remained white, latterly with black and buff trim. (After several years, her forecastle was repainted black.) There was no change in her stack colours, for Upper Lakes & St. Lawrence, which earlier had used a green stack with white band and black top, adopted the Playfair colours as its own when it acquired his vessels .

The date is July 1938 and RALPH BUDD, in Upper Lakes & St. Lawrence colours, is again at Toronto Elevators. J. H. Bascom photo.

Over the years, RALPH BUDD, which still kept her old name, operated very successfully for Upper Lakes. She retained her 'tween deck, although she did not carry package freight and was used almost exclusively in the grain trade from the Canadian Lakehead to such ports as Goderich, Port Colborne and Toronto. A number of the U.L.&St.L. steamers had sufficient power to tow barges, and RALPH BUDD most certainly fell into that category with her big quadruple-expansion engine. DOUGLASS HOUGHTON, MAUNOLOA II, JAMES B. EADS, JOHN ERICSSON and RALPH BUDD usually could be seen with a barge in tow, the company also having acquired the barges JOHN FRITZ, JOHN A. ROEBLING, GLENBOGIE, BRYN BARGE, 137 and ALEXANDER HOLLEY from other operators. Each of the steamers might regularly be seen with a particular barge, but assignments varied. In fact, a steamer would often arrive at her destination with one barge in tow, unload her own cargo, and then leave the barge to be unloaded later, clearing port with a different barge which in turn had been left behind by the last steamer to call there. In this manner, the fleet's steamers would not be delayed lying idle and waiting for barges to be unloaded. This shifting of barges could often be seen at Port Colborne and at Goderich.

However, as barges could not easily be handled in the Welland Canal and only rarely were brought to Lake Ontario (usually only to Toronto for winter storage and, even then, only in the last few years of their careers), and as the BUDD was a good towing steamer, she appeared in Toronto a bit less frequently than did some of the company's other vessels. She often wintered at Port Colborne with storage grain for the Maple Leaf Milling elevator there.

The 1950s saw RALPH BUDD entering her sunset years. She was not the oldest operating lake vessel by any means, but she certainly was of ancient appearance in that her superstructure had undergone very little change over the years and her turn-of-the-century vintage was quite obvious. As well, her hull had begun to flatten out a bit due to age and hard use, and her looks suffered from the loss of sheer. During this period, she was given a new and heavier stack, and she lost her melodious, triple-chime steam whistle.

During the mid-fifties, RALPH BUDD's home port was changed from Midland to Toronto, the latter being the traditional port of registry used by Upper Lakes & St. Lawrence. As well, in 1959, the company finally tired of her old and then-meaningless name, and rechristened her (c) L. A. McCORQUODALE in honour of a prominent member of the then-affiliated Maple Leaf Mills Ltd., upon which the fleet depended for much of its grain traffic. Then, in 1961, the Upper Lakes and St. Lawrence Transportation Company Ltd. was reorganized as Upper Lakes Shipping Ltd., Toronto, as the fleet moved ahead with a major programme of modernization which in just a few years would see all of the older and less efficient ships, including the barges, purged from the roster. The ownership change resulted in the addition of a white-edged black diamond to the McCORQUODALE's funnel colours.

In 1961, Upper Lakes Shipping did something very strange indeed. It attempted to create a new package freight service between Toronto and Lake Superior ports using two of its older ships that were not required in other trades. The two steamers chosen were the McCORQUODALE and the 1894-built JAMES B. EADS, (a) GLOBE (99). The EADS, of course, also had been designed and built as a package freighter, although she had not served in that capacity since the very early stages of her career.

The two boats were prepared for their new trade over the winter of 1960-61. At Port Weller, two small whirly cranes were fitted on the deck of McCORQUODALE, forward of the doghouse. At the same time, her two heavy old masts were removed and in their place were fitted two short, unraked pipe masts, the fore stepped right behind the pilothouse and the main immediately ahead of the boilerhouse. (These new masts did nothing whatever for the ship's appearance.) The steamer was, of course, still equipped with the sideports that she had used many years ago, but we do not believe that much if any use was made of them during her short spell as a "new" package freighter for Upper Lakes Shipping.

On December 7, 1963, L. A. McCORQUODALE made her last trip down the Welland Canal. Photo at Homer Bridge by J. H. Bascom.

At Toronto, the U.L.S. package freighters docked at Pier 4 near the foot of John Street, which years before had been used for many general cargo services by both lakers and salt water vessels. The U.L.S. service, however, was not successful, for the boats were old and slow, and lacked modern equipment, and they were completely out-classed by the up-to-date and speedy package freighters then being operated by Canada Steamship Lines Ltd. As well, Upper Lakes Shipping had no previous experience in the general cargo service and entered the trade "cold". The service lasted through the 1961 season and into 1962, but was phased out during the latter year. L. A. McCORQUODALE was returned to the grain trade by 1963. although she retained her deck cranes.

It was, however, costing more and more to keep the old steamer in service. Her big "quad" required the feeding of copious quantities of bunker coal to her boilers, at ever-increasing cost. In addition, she was not a good boat for the grain trade, for her 'tween deck made unloading a difficult procedure as elevator legs had to be guided down through two sets of hatches to access the grain in the lower holds. As well, several new ships had been added to the fleet and more were on the way. Upper Lakes Shipping still needed the cargo capacity of some of its older vessels, but McCORQUODALE was not one of them, and the decision was made to retire her. She made her last passage down the Welland Canal on Saturday, December 7, 1963, bound for Toronto with a storage cargo of grain for Maple Leaf Mills.

The McCORQUODALE would never sail again. She lay at Toronto for the next three seasons, spending most of her time in the old Spadina Avenue slip, beside the building in which her owner's offices were then located, and occasionally a load of storage grain was put in her by Maple Leaf Mills. But by 1966, she had reached the end of her usefulness in even this humble service, and she was sold to United Metals Ltd., Hamilton, for scrapping. She was towed to the company's scrapyard at the foot of Strathearne Avenue, in the east end of Hamilton harbour, and there she was dismantled. This same scrapyard also broke up a number of other steamers and barges from the Upper Lakes Shipping fleet.

L. A. McCORQUODALE was scrapped when she was only 6l years of age, much younger than many of the other vessels in the Upper Lakes Shipping fleet. Nevertheless, at the time of her demise, she was the last recognizable former Great Lakes Transit Corporation package freighter left on the lakes. With her to the scrapyard went the last chance for observers to see first-hand what the beautiful old G.L.T.C. package freighters looked like. As a class, they had been perhaps the most distinctive freighters ever built on fresh water, and the fact that they were extremely well designed and built is evidenced by their service in World War II, when many of them were rebuilt and sent to salt water, and managed to survive the conflict as well as the rigours of operation on the deep seas.

Ed. Note: Information concerning the various trials of SUPERIOR/RALPH BUDD on Lake Superior can be found in The Shipwrecks of Lake Superior by Dr. Julius F. Wolff, Jr., published in 1979 by the Lake Superior Marine Museum Association Inc., Duluth.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.