Table of Contents

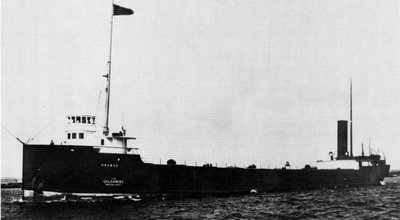

Back in April of 1984, exactly one year ago, we featured as our Ship of the Month No. 128, the steamer MARTIAN (II), (a) NEPTUNE (37), (b) WILLIAM M. CONNELLY (48). It seems only fitting that we now review the story of one of that vessel's many sisterships, in part because it is so unusual that a fleet of six almost exact sisters should be built for the same owner, and as well because the ship that we now feature has been the subject of numerous specific requests made by various members of this Society. In addition, the vessel was lost fifty years ago last fall in an accident that not only ended her own career but that of another famous steamer as well, and it is only proper that such an anniversary should be acknowledged, even if somewhat belatedly. And as if we needed a further reason to feature W. C. FRANZ at this time, we have recently discovered some very interesting photographs of the ship that were taken a scant two months before her demise, and considering that they came from the camera of our late Treasurer, Jim Kidd, we felt that they ought to be shared with all of our members.

W. C. FRANZ began her life in the fleet that was operated by Joseph C. Gilchrist, one of the giants of the lake shipping industry in the latter part of the nineteenth century, and the early twentieth century. Gilchrist was well established in lake shipping by the 1880s, and at various times was accompanied in his enterprises by John W. Moore and J. H. Bartow of Cleveland, and by his cousin, Frank W. Gilchrist. Joseph C. Gilchrist was an artful entrepreneur, adept at the formation of various syndicates which provided the money to build the various groups of steel-hulled steamers which he added to his fleet around the turn of the century. In fact, at that time, the Gilchrist fleet was caught up in a period of very rapid expansion, one that eventually would lead to its downfall, although other factors combined in an unfortunate manner to destroy one of the greatest of the U.S. flag lake fleets.

Gilchrist made a habit of ordering his steel-hulled bulk carriers in what might best be described as "classes", or groups of sisterships. In addition to several smaller groups, one of these classes contained five steamers, one had six, and the largest of them all comprised eight ships. The first of the classes was made up of six steamers that were to become known as the "planets", for all of the ships were named for planets in our Solar System. The contracts for their construction were let during 1900, two of the hulls being awarded to the Detroit Shipbuilding Company, Wyandotte, Michigan, and four to the American Shipbuilding Company, Lorain, Ohio. The two Wyandotte boats were Hulls 139 and 140 (MARS and URANUS), while AmShip's Hulls 305 to 308, respectively, were christened NEPTUNE, SATURN, VENUS and JUPITER.

The Lorain yard launched the first of its hulls of this class on December 15,1900, and put an additional boat into the water in each of the three succeeding months. The first Wyandotte boat did not go into the water until March 9,1901, and URANUS, the last of the six to be launched, was not put afloat until Saturday, April 20, 1901.

URANUS (U.S. 25339) was enrolled at Cleveland, Ohio, the normal home port of the fleet, but as was the Gilchrist custom, the port of registry painted on her stern was Fairport. She was 346.0 feet in length, with a beam of 48.0 feet and a depth of 28.0 feet, and her tonnage was registered as 3748 Gross, 2943 Net. She was powered by a triple expansion engine which had cylinders of 22, 35 and 58 inches, and a stroke of 42 inches, which produced Indicated Horsepower of 1,200 (later reported as 1,480). Steam at 170 p.s.i. (later recorded, erroneously, we believe, as 120) was produced by two coal fired, single-ended Scotch boilers, which measured 13 feet 2 inches by 11 feet 6 inches (also noted as 12 feet by 12 feet) each. The machinery was built for the vessel by the shipyard.

Young photo, dated 1910, shows URANUS upbound above the Soo Locks.

URANUS and her sisters had a cargo capacity of only some 5,580 tons, and today's observer might well wonder why the ships were not built to larger dimensions, considering the rapid advancements in steel ship design and construction that occurred around the turn of the century. As contemporary reports reveal, J. C. Gilchrist was firmly of the opinion that ships with a capacity of approximately 5,500 tons were the most economical to operate, and were the best lakers for handling at docks and for the obtaining of cargoes. However, cargo-handling technology was also growing rapidly, and the wharves at lake ports were being equipped with newer and more efficient machinery. As a result, Gilchrist soon acknowledged that larger vessels could be useful, and each successive class of new ships that he built sported larger dimensions. In fact, by 1906, Gilchrist was taking delivery of steamers that boasted a cargo capacity almost twice that of the little URANUS and her sisterships.

URANUS was a handsome ship, similar in appearance to many of the steel lakers that were then being turned out by various lake shipyards. However, she and the other "planets" were considerably less fancy in design than many other steamers of their day, and their plainness was particularly remarkable when they were compared with the extremely good-looking ships that were being built to both the design and the order of Capt. John Mitchell.

URANUS was built with three cargo compartments in her hull, with access through ten hatches on 24-foot centres, each hatch being eight feet in width fore-and-aft. She had a half-forecastle, enclosed for about half its length by a closed steel rail. Her small rounded five-windowed pilothouse sat on the forecastle head, immediately forward of the small texas cabin which contained the master's quarters and office. As was the fashion of the day, an open navigation bridge was provided on the monkey's island atop the pilothouse. Protection for those on watch there was provided by a waist-high closed rail and a canvas weathercloth, and an awning was stretched overhead for shelter from the summer sun. A tall and well-raked foremast rose up out of the texas house.

The steamer's quarterdeck was flush with the upper deck, and on it was located her after cabin, a squarish house which was surrounded by a closed deck rail. The cabin had only a few large windows, but light was admitted from overhead (particularly into the officers' mess, the most important interior space) by a prominent clerestory. The mainmast was stepped abaft a rather heavy funnel, both of which were raked but not to the same degree as was the foremast. There was an open rail around the after end of the boat deck, behind the lifeboats, but no rail at all, either open or closed, originally graced the top of the boilerhouse at the forward end of the after cabin. The "planets" looked rather "bald" aft as a result of this lack of a bunker rail. The boilerhouse itself was not indented on each side as it was, for instance, on the Mitchell boats, but rather was flush with the sides of the rest of the after deckhouse.

URANUS and her sisters were given the usual Gilchrist livery. Her hull was black and she had a grey boot-top which rose so high that it was even visible when she was running loaded. Her name appeared on her bows in small but rather fancy letters (which may have been white, but appear in some photos to have been yellow or gold, or perhaps natural brass), and the company's name was carried in larger white letters below. The cabins were white, and the stack was all black. The houseflag that all of the Gilchrist boats flew was dark blue with a large white letter 'G'.

In keeping with the Gilchrist syndicate system, URANUS was originally owned by Joseph C. Gilchrist and a group of stockholders. In 1903, however, she was absorbed into the Gilchrist Transportation Company, Cleveland, when all of the Gilchrist vessel holdings were consolidated into one company. Joseph Gilchrist disliked having his ships tied up with season charters (modern vessel operators seem to be of the opposite opinion on this point) and thus URANUS carried very little iron ore. The fleet took many "wild" charters in coal, and secured a very large proportion of the grain cargoes to Buffalo each year, so it is likely that URANUS spent most of her time hauling grain and coal. She apparently did so without being involved in any untoward occurrences .

The heyday of the much-expanded Gilchrist fleet was indeed brief. In recent years, we have seen the effects of too-rapid expansion on the financial viability of a fleet, and the Gilchrist firm provided an early example of the fate awaiting operators who overburden themselves with debt. Gilchrist built up the second largest fleet operating on the lakes under the American flag, but the piper had to be paid for the construction of so many expensive new ships. The early years of the new century were boom times, but the shipyards were taking an immense share of the Gilchrist earnings.

Unfortunately, the 1907 navigation season brought with it a general business panic, and it hit not long after the fleet had taken delivery of the largest ships it was ever to own. There were far fewer cargoes available than there were boats to carry them, and many steamers were forced into ordinary. Struggling to pay off the debt incurred in the construction of twenty-seven new ships in little more than half a decade, the Gilchrist fleet was truly up against it. The company might have been able to pull through had its founder remained at the helm, for he was an astute vessel manager. Under the pressure of the situation, however, Joseph C. Gilchrist suffered a severe and completely debilitating stroke during 1907. He lived until 1919, but he never recovered his health, and he was never again able to take any active part in the operation of his own company.

F. M. Osborne, of Cleveland, was chosen to be the new president of the Gilchrist Transportation Company, and the actual operation of the firm was left to Joseph A. and John D. Gilchrist, the sons of Joseph C, and to Frank W. Gilchrist, Jr., the son of Joseph C.'s cousin. They were assisted by marine superintendent Capt. J. L. Weeks, and chief engineer James D. Mitchell. The fleet struggled on, but with no improvement in its situation, and a railroad man by the name of S. P. Shane was brought in as general manager. Still the firm was unable to pull itself out of the mire, and the shareholders could not agree on what to do. The company went into receivership in January 1910, and the receivers appointed by the court were Shane and General George A. Garretson, president of the Bank of Commerce, which had financed the construction of many of the Gilchrist fleet's new vessels.

With the passing of the years, the fortunes of the Gilchrist fleet deteriorated even further, and with no hope of any improvement, the sale of the whole fleet was ordered by the District Court, Eastern Division of the Northern District of Ohio, in August of 1912. Shane and Garretson tried to sell as many of the ships as they could, but they were only able to peddle a few of them, and the remainder were sold at auction on March 6, 1913. It is interesting to note that, on January 15, 1913, the very day that the court ordered the sale of the fleet by auction, Shane and Garretson managed to sell two of the steamers to Canadian operators.

The two that changed hands on that day were URANUS and SATURN, both of which were acquired by Roy M. Wolvin, the Winnipeg entrepreneur who was then involved in the machinations that led, later that year, to the formation of Canada Steamship Lines. URANUS and SATURN, however, never became part of the C.S. L. fleet, even though two of their sister "planets" did. Instead, Wolvin almost immediately resold the pair to the Algoma Central and Hudson Bay Railway Company, of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

SATURN was re-registered at the Soo as (b) J. FRATER TAYLOR, while URANUS became (b) W. C. FRANZ (C.130775), also enrolled at Sault Ste. Marie. The Canadian inspectors recalculated her tonnage as 3429 Gross, 2030 Net, and measured the output of her engine as 169 Nominal Horsepower. She was named in honour of William Charles Franz, who at the time was vice-president of the Cannelton Coal Company, a U.S. subsidiary of Algoma Steel. Five years after the steamer took his name, Franz became president of the Algoma Steel Corporation Ltd.

W. C. FRANZ was painted in the usual Algoma Central colours of her day, with a black hull and white cabins. Her stack was black with two red bands and a white band between them. Of course, in that period, the Algoma ships were not adorned with anything as fancy as the ""bear" insignia that they carry today. The only thing that appeared on the bow of an Algoma freighter back then was her name, printed in plain white letters.

When the FRANZ entered the Algoma fleet, however, something rather strange happened to her. During the latter years of her Gilchrist service, the ship had been given a small and rather flimsy wooden upper pilothouse which had no sunvisor but which sported eleven windows in its rounded front. This structure provided only basic shelter for the officers on watch and we doubt that those closeted within could ever have been described as being comfortable. Whether this upper house had deteriorated in condition, or whether Algoma simply disapproved of enclosed pilothouses for its officers (as did several fleets of that period), we do not know, but one of the first things the new owners of W. C. FRANZ did was to remove the upper cabin. For the next half-decade, at least, the steamer operated with an open navigation bridge, just as she had when she was first built.

The camera of the late James M. Kidd caught W. C. FRANZ unloading at Toronto Elevators on September 9, 1934, just over two months before her loss.

The FRANZ operated for Algoma Central in the grain, coal and ore trades, and she and her sister proved to be very successful. On May 5. 1918, W. C. FRANZ was at Cleveland when she suffered a fire; damage was assessed at $8,000 - a princely sum in those days. She was soon rebuilt and it may have been at this time that she was given a new upper pilothouse. It had fifteen sectioned windows in its rounded front, and was considerably larger than the old upper cabin in that it extended well back over the texas cabin. It never did have a full sunvisor, but it did have a single small shade over the centre window. For a while, the windows were left in the lower pilothouse, but later they were all shuttered over, with one small porthole being cut into the shutter on the centre window of the old cabin. An open boilerhouse rail seems to have appeared at about the same time as the new pilothouse.

On November 23. 1919. the small wooden steamer MYRON foundered on Lake Superior, some ten miles west of Whitefish Point. Seventeen members of her crew were lost, and the only survivor was the steamer's master, Capt. Walter R. Neale. W. C. FRANZ arrived in the area where the MYRON had gone down, and found Capt. Neale perched atop his ship's pilothouse, which had floated free of the sinking steamer. He was soon taken aboard the FRANZ, and thence to safety ashore. The FRANZ again made the press when, on April 18, 1922, she was one of the last ships ever to sight the 108-foot Dominion government tug LAMBTON, which was upbound out of the Soo for Lake Superior. LAMBTON foundered, with the loss of all hands, in the vicinity of Caribou Island on April 19, 1922.

Jim Kidd climbed the stairs at the bayward end of Toronto Elevators to catch this scenic view of the deck of W. C. FRANZ on September 9, 1934.

During the early 1938s, W. C. FRANZ frequently appeared in Toronto Harbour with grain consigned to Toronto Elevators Ltd. She managed to keep fairly active even during the height of the Great Deoression, [sic] when many other lake vessels spent a great deal of time at the wall. She wintered at Sarnia in 1930-31, and again was there for the winter of 1931-32. She spent the winter of 1932-33 at Port Colborne, and the winter of 1933-34 at Midland. She spent the winter of 1934-35 at the bottom of Lake Huron, just as she has every winter since.

We now briefly shift our attention to the Great Lakes Transit Corporation's steel-hulled package freighter EDWARD E. LOOMIS (U.S.81733). She was originally WILKESBARRE, which was built in 1901 at Buffalo as Hull 92 of the Union Dry Dock Company. Launched on Saturday, December 1, 1900, she was 381.7 feet in length, 50.5 feet in the beam and 28.0 feet in depth, with tonnage of 4279 Gross and 3437 Net. She was powered by a quadruple expansion engine, 20, 30, 43 and 63 by 42, and steam was provided by three coal-fired Scotch boilers, 12.5 feet by 12.25 feet. This machinery came from the Dry Dock Engine Works, Detroit, and was typical of the power that was installed in the big line package freighters of the period.

A typically handsome package freighter, with raked funnel and spars, and with her pilothouse set back off the forecastle, WILKESBARRE was built for the Lehigh Valley Transportation Company of Buffalo, which was the lake shipping affiliate of the Lehigh Valley Railroad. The Panama Canal Act of 1915 forced the railroads to divest themselves of their lake steamer lines and, as a result, the Great Lakes Transit Corporation was formed in 1916 to operate the package freighters that formerly had run for the railroads. The Lehigh Valley vigourously opposed the government over the implementation of the Act, and the matter wound up in protracted litigation. As a wartime measure, the U.S. Railroad Administration took over the operation of the Lehigh Valley boats in 1917. The court eventually rules against the Lehigh Valley in its dispute with the government, and so the remains of its fleet, including WILKESBARRE, joined the Great Lakes Transit Corporation in 1920.

WILKESBARRE had been painted black with a grey boot-top. She had white cabins, and a black stack with a red band, a black diamond, and the letters 'LV' in white. When she joined the Great Lakes Transit fleet, she became (b) EDWARD E. LOOMIS and was painted in the livery which G.L.T.C. took over from the Western Transit Company, namely a brown hull, white cabins, and black stack with an orange band. In 1925, the entire Great Lakes Transit fleet was given the colours of the old Anchor Line, with white hulls and green boot-tops, white cabins, and crimson stacks with a black smokeband.

EDWARD E. LOOMIS and her sister, W. J. CONNERS, (a) MAUCH CHUNK (20), were among the largest package freighters ever operated by Great Lakes Transit, but the active career of the LOOMIS was brought to a premature end in its 34th year. Early on the morning of Wednesday, November 21st, 1934, the LOOMIS was downbound on Lake Huron on one of her regular runs. The G.L.T.C. boats were all equipped with powerful machinery that gave them a good turn of speed, for they operated on a strict schedule, and it has been said that one could almost set one's watch by their movements.

Her bow damage never repaired, EDWARD E. LOOMIS lay in the Buffalo City Ship Canal after the FRANZ collision. Kidd photo is dated October 29, 1938.

The morning of November 21, 1934, also found W. C. FRANZ out on Lake Huron. She was upbound light for Fort William from Port Colborne, after unloading a grain cargo for trans-shipment down the canals. Visibility on the lake was poor as a result of a combination of fog and vessel smoke. At about 3:25 a.m., when the FRANZ was some thirty miles southeast of Thunder Bay Island, she was rammed by the downbound LOOMIS. The FRANZ was mortally gored in the collision, and she gradually filled with water and foundered. Most of the crew of the FRANZ were able to leave their ship safely, and were picked up by the LOOMIS, but four men were not so fortunate. During the confusion and tumult that immediately followed the collision, four of the crew were plunged into the cold waters of Lake Huron and were drowned.

The Lake Carriers' Association report concerning the accident stated that "as the FRANZ remained afloat for almost two hours, with the steamer REISS BROTHERS standing by while the LOOMIS took aboard the sixteen survivors, it is probable that the loss of lives would have been averted but for the unfortunate incident of haste". Of course, the fact that the accident occurred in the middle of the night, when many of the crew would be asleep, meant that the circumstances were ripe for panic to develop. The accident, however, was proof, if any were needed, that calm and orderly behaviour is essential if life is to be preserved in a marine emergency.

The bow of EDWARD E. LOOMIS was severely damaged, but she was in no danger of sinking, and she was able to proceed on her way after the collision. She put the FRANZ survivors ashore at Port Huron, Michigan, and then made her way to Buffalo, where she was laid up in the old City Ship Canal. At the time, Great Lakes Transit was only operating a portion of its fleet, the effects of the Great Depression having hit hard at the company's general cargo business. Accordingly, the G.L.T.C. simply fitted out one of its laid-up vessels to take the place of the LOOMIS, and the latter remained idle, her extensive bow damage unrepaired.

EDWARD E. LOOMIS lay at Buffalo for five and a half years, while her condition deteriorated to the point that she became an eyesore, although there were many other idle vessels lying in almost every U.S. lake port. The LOOMIS gradually took on a nasty list to starboard, and her once-gleaming paint became streaked with rust. Early in 1940, the Great Lakes Transit Corporation, by then only a shadow of its former active self, sold the LOOMIS to the Steel Company of Canada Ltd. for scrapping. She was towed out of Buffalo and down the Welland Canal to Hamilton, Ontario, during May of 1940 by the tugs PROGRESSO and PATRICIA McQUEEN. During August of the same year, she was reduced to a pile of scrap to be fed into the hungry Stelco furnaces in aid of the war effort. A minor complication in the scrapping process was the job of breaking up the many tons of cement that Great Lakes Transit had poured into the bow of the LOOMIS in an effort to keep her afloat after the accident .

Memories of the lost W. C. FRANZ remained with the Algoma Central fleet for many years, as there were numerous observers who recalled seeing the steamer in service. As well, her sistership, J. FRATER TAYLOR, which was renamed (c) ALGOSOO (I) in 1936, remained active in the fleet until the close of the 1965 season, at which time she was sold for scrapping in Spain. If the FRANZ had not been out on Lake Huron on that cold morning in the autumn of 1934, she also might have lived to carry an "Algo" name, perhaps for another three decades of service.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.