Table of Contents

| Title Page | |

| Meetings | |

| The Editor's Notebook | |

| Greetings of the Season | |

| Marine News | |

| Ship of the Month No. 133 Northumberland | |

| Lay-up Lists | |

| Table of Illustrations |

Much has been said in these pages over the years concerning the various passenger vessels that have operated out of Toronto. Most of the major steamers have been reviewed, but one that we have not featured previously, and for which we have received numerous requests, is the Port Dalhousie steamer NORTHUMBERLAND, which undoubtedly was one of the most handsome excursion ships ever operated anywhere on the Great Lakes. As a Christmas special for our members, and as a reminder of the warm and pleasant days of summertime, we present here the story of this famous ship. We hope that our readers enjoy it as much as we enjoyed putting it together.

During the first six decades of this century, rail passenger services in St. Catharines and the surrounding areas of the Niagara Peninsula were operated by the Niagara, St. Catharines and Toronto Railway Company, which had been formed in 1899. The company was at first owned by interests in New York State and managed by parties closely associated with the famous MacKenzie and Mann group of Toronto, but in 1904 control of the electric railway passed to the Toronto interests. One of the principal services provided by the N.S. & T. for most of its life was its main line, which carried excursionists from St. Catharines and environs to the Niagara Falls tourist area.

By the turn of the century, the Niagara Navigation Company Ltd. was well established in its service between Toronto, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Lewiston and Queenston, but other operators had been running boats out of Toronto to both Grimsby and Port Dalhousie, the latter port serving the City of St. Catharines, to which there was much passenger traffic from Toronto. About the time of the formation of the N.S. & T. Railway, three associates of the MacKenzie and Mann group, namely Zebulon Aiton Lash, Q.C., J. H. (James Henry) Plummer and Joseph W. (later Sir Joseph) Flavelle, purchased the assets of the Lakeside Navigation Company and formed the Niagara, St. Catharines and Toronto Navigation Company. The navigation company became a wholly-owned subsidiary of the railway company in 1902, and control of both was assumed by the Canadian Northern Railway (another MacKenzie and Mann enterprise) in 1908.

The new navigation company's first passenger steamers were the small wooden propellor LAKESIDE and the larger steel sidewheeler GARDEN CITY. Together, they held down the flourishing service between Toronto and Port Dalhousie, a trade that was enhanced by the development by the N.S. & T. of Lakeside Park, which was located on the west side of the lower level of Port Dalhousie harbour, below Lock One of the Welland Canal. Lakeside Park, remnants of which can be seen to this day, provided amusements, restaurant and picnic facilities on the shore of Lake Ontario, and served as an added attraction for Torontonians to escape to the N.S. & T. steamers during the hot summer months.

LAKESIDE was the first of the older steamers to be retired, and she was sold in 1911 and converted to the tug (b) JOSEPH L. RUSSELL (See Ship of the Month No. 42, October 1974 issue). She was replaced by the steamer DALHOUSIE CITY, a much larger propellor, which was built for the N.S. & T. in 1911 by Collingwood Shipbuilding Company Ltd. (See Ship of the Month No. 75, May 1978 issue). DALHOUSIE CITY and GARDEN CITY ran together for only a few years, for the relatively small and aging (1892) GARDEN CITY was frequently diverted to other routes around Lake Ontario and had been permanently retired by 1917. She was sold to operators in the Montreal area in 1922.

After the end of the First World War, passenger service on the Port Dalhousie route began to pick up once again, and the company began to look around for a second boat, for DALHOUSIE CITY could not accommodate all of the traffic by herself. The N.S. & T. decided to purchase a used vessel rather that to incur the cost of building a new one, and it was thus that the beautiful NORTHUMBERLAND came to Lake Ontario.

NORTHUMBERLAND (C.96937) was a steel-hulled, twin-screw passenger steamer which was built in 1891 as Hull 955 of Wigham Richardson and Company Ltd., Newcastle-on-Tyne, England. She was 220.0 feet in length, 33.1 feet in the beam, and 20.4 feet in depth, with tonnage of 1255 Gross and 542 Net. She was powered by two triple expansion engines, each having cylinders of 17 1/2, 27 1/2 and 46 inches, and stroke of 33 inches. They produced 243 Nominal Horsepower (2,500 total Indicated Horsepower), operating on 160 p.s.i. steam pressure supplied by two coal-fired, double-ended Scotch boilers. NORTHUMBERLAND regularly operated at a speed of 14 miles per hour.

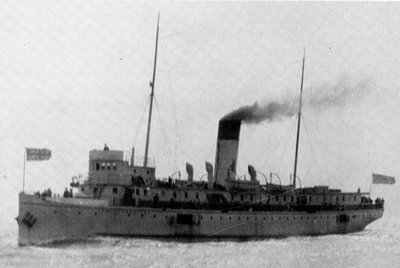

Photo by Rowley W. Murphy shows NORTHUMBERLAND in 1920, her first season on the lakes. Her boat deck is not yet available for passenger use.

NORTHUMBERLAND was built for the Charlottetown Steam Navigation Company for service between Pictou, Nova Scotia, and Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. She was registered at Charlottetown and carried the name of that port on her stern for her entire lifetime. It is interesting to note that EMPRESS, a very similar steamer in appearance to NORTHUMBERLAND, although fifteen years younger, was built for the same company by the same shipbuilder in 1906. EMPRESS, although almost a duplicate of NORTHUMBERLAND, as photographs indicate, was slightly larger, 235.0 x 34.2 x 20.0, 1342 Gross and 612 Net.

The Charlottetown Steam Navigation Company discontinued operations in 1916 and NORTHUMBERLAND was sold to the Dominion Government, which took over the service between Prince Edward Island and the mainland. EMPRESS was sold to the Canadian Pacific Railway for its ferry route between Digby, Nova Scotia, and St. John, New Brunswick. NORTHUMBERLAND was replaced on her original service in 1920, and at that time the Canadian National Railway decided to bring her to Lake Ontario.

The depressed business conditions of the first war era had brought an end to the various transportation services which had been operated across Canada by the Canadian Northern Railway and its assorted subsidiaries and affiliates, all of which were run by the MacKenzie and Mann interests. In return for salvaging the Canadian Northern from its precarious financial situation, the federal government demanded that its assets be turned over to the government, which already held a large stock interest in the group. It was thus that the N.S. & T., as well as its navigation company, came to be part of the Canadian National Railway, which the Dominion Government formed in 1918.

NORTHUMBERLAND entered service on Lake Ontario during 1920, running with DALHOUSIE CITY on the Port Dalhousie route out of Toronto. The vessels were chartered to a Canadian National subsidiary, the Niagara, St. Catharines and Toronto Navigation Company Ltd., and actual ownership of the two ships was later turned over to the navigation company. In subsequent years, the service was generally known as "Canadian National Steamers", operating "in connection with Niagara, St. Catharines and Toronto Railway".

NORTHUMBERLAND was a beautiful steamer indeed, although hardly suitable for day-boat service on the lakes in her original form. Her hull, although not given much sheer, had fine lines to suit her original salt-water service. She had a sharp, flaring bow, and a typical "Swan Hunter" stern (as such came to be known), with a graceful and deeply-undercut counter across which were the raised letters of her name and port of registry, incorporated into a fanciful scroll design which included the coat of arms of Prince Edward Island. The hull sported two sets of sideports on each side for cargo and passenger loading. The deck rail was open all the way around the upper or "promenade" deck, with only a very short section of closed bulwark forward.

On the upper deck was a long steel deckhouse for passengers. It was totally "bald", that is, it was devoid of any overhang of the boat deck above to give shelter to those on the open deck, except for that area immediately athwart the stack, where there was a short overhang on which the lifeboats (two on each side) sat under davits. A very large wooden pilothouse and a small master's cabin sat far forward on the boat deck, with an open navigation bridge located on the monkey's island. The rounded front of the pilothouse contained nine windows, and was particularly notable because of its fancy wooden panelling. Bridge wings were provided at the far forward end of the boat deck, and they protruded out to the sides of the ship. Interestingly enough, there were no wings on the open bridge above.

Interesting view c. 1924 has NORTHUMBERLAND in winter quarters in the old Yonge Street slip, Toronto. On the right are MODJESKA and TORONTO.

NORTHUMBERLAND'S most notable features were her two very tall and heavily-raked masts, and her tall and very thick stack. The funnel, which seems to have been painted all black when the ship first came to the lakes, was raked to match the masts, and it gave her an even more racy appearance because its top was cut parallel to the water rather than at a right-angle to the rake. One peculiar feature of the stack was that it had steam scape pipes running up both its front and back sides. Four enormous ventilator cowls protruded from the boat deck and encircled the stack. The melodious old triple-chime steam whistle from GARDEN CITY was given to NORTHUMBERLAND and it served as her voice for the rest of her life.

For her new duties on the lakes, NORTHUMBERLAND was given the same colours as DALHOUSIE CITY. Her stack became cream with a wide black smokeband, and her cabins also were cream. The hull was grey with cream trim. As the seasons passed, the grey and cream paint on the hull and cabins took on a darker tint, but the cream colour of the lower portion of her stack remained the same throughout the years.

To make NORTHUMBERLAND more appealing to cross-lake excursionists, the ship was overhauled and numerous alterations made during her first lay-up on the lakes at Toronto during the winter of 1920-1921. Previously, her boat deck had not been open to passengers, and the necessary changes were then put in hand to convert this area for their use, thus providing the considerable additional deck space which the lake excursion trade required. To provide passengers with some shelter against the elements in this deck area, a permanent canopy was built over that section of the boat deck between the pilothouse and the stack.

Originally, four staterooms were fitted at the forward end of the dining saloon. These were removed and the dining room itself was turned into a new lounge with a hardwood floor suitable for dancing. The forward end of the deckhouse (immediately beneath the pilothouse) was moved back about ten feet in order to provide more open deck space forward. New plumbing was installed throughout the boat, all her decks were refinished, a new galley and dining rooms were provided for the officers and crew, and the machinery was completely overhauled. The improvements doubled the ship's licenced passenger capacity and enabled her to accommodate 1213 passengers. As well, to make the promenade deck more comfortable for passengers, the open deck areas astride the deckhouse were covered by canvas awnings which extended outward from the cabin to the sides of the steamer's hull.

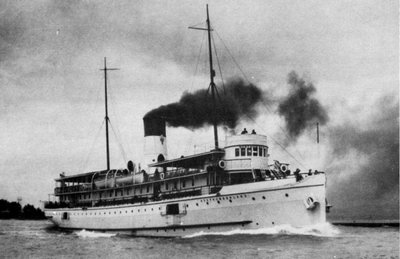

Scenic Murphy photo shows NORTHUMBERLAND inbound at the Port Dalhousie piers in the mid-1920s. Note the shelter forward on her boat deck.

About 1927, further upper deck improvements were made aboard NORTHUMBERLAND. A permanently covered dance floor was fitted aft of the stack so that those wishing to dance on warm summer afternoons or evenings could do so whilst enjoying the refreshing lake zephyrs. A year or two after this dance deck was added, the sides of the boat deck were extended out to the hull line, thus doing away with the necessity for canvas awnings over the promenade below.

One other minor change in NORTHUMBERLAND'S deck arrangements took place during her years on the lakes. When she first arrived, there was only one stairway from the promenade deck forward to the boat deck. It was located on the port side, immediately in front of the pilothouse, and was intended for the use of the crew. Later, and probably around the time that the after dance area was added, a second stairway was added forward to accommodate heavy passenger movement about the decks. Two other stairways located aft of the stack gave access to the upper deck; strangely, they rose athwartship rather than in the more usual fore-and-aft alignment.

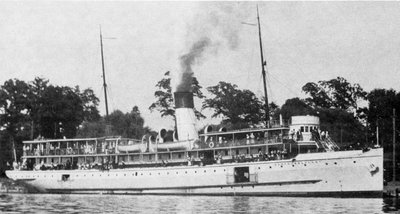

Murphy photo c.1930 shows NORTHUMBERLAND outbound at the Toronto Eastern Gap in rough weather. Note the covered dance deck aft.

These various alterations to NORTHUMBERLAND'S superstructure greatly added to her "top-hamper", and they may have lessened but certainly did not ruin her beautiful yacht-like lines. There are those who feel that, after these additions to her upperworks, NORTHUMBERLAND lost most of her original grace. While it is true that she no longer looked like a coastal steamer, she fitted in well with the conventions of lake excursion service and, in our opinion, remained one of the most handsome vessels ever so employed on the lakes despite the alterations. Excursionists of the day must have thought so too, for she was immensely popular amongst the travelling public during her three decades of Lake Ontario service.

With NORTHUMBERLAND added to the route, the N.S. & T. was in a position to handle the heavy passenger traffic that developed between Toronto and Port Dalhousie during the 1920s. As well, with two large vessels now on the run, the company actively sought to attract large excursion parties to its boats, and it was through such school, social club, and church group excursions that many Torontonians came to make their very first cross-lake trip.

Despite the fact that they operated successfully together, NORTHUMBERLAND and DALHOUSIE CITY were completely mismatched vessels, very different in appearance. In contrast with NORTHUMBERLAND, DALHOUSIE CITY was a more traditionally designed lake steamer, with a staid appearance and decks that were sponsoned. NORTHUMBERLAND could make a one-way crossing in two hours and ten minutes, while the slower DALHOUSIE CITY required two and a half hours, and even more in rough weather, for she was a notoriously "bad actor" in heavy seas. NORTHUMBERLAND had comfortable plush seat covers in her lounges whereas DALHOUSIE CITY had wooden slat seats, such as one might have found in city streetcars of the day. All in all, NORTHUMBERLAND was a much more comfortable steamer than was her running-mate, and she was favoured by many passengers, especially those who were troubled with "mal de mer" and who did not appreciate DALHOUSIE CITY's propensity to roll heavily when the lake kicked up a swell.

On a typical summer afternoon c.1930, the camera of Rowley Murphy captured NORTHUMBERLAND moored on the east side of Port Dalhousie harbour.

There was one other notable difference between the two boats. DALHOUSIE CITY was relatively quiet when running, whereas NORTHUMBERLAND, possibly because of her twin screws and additional power, tended to make a very distinctive thumping sound when operating at speed. This sound was not particularly noticeable from on board, but it could be heard very easily from ashore when the ship was approaching, and observers, without even looking, could readily tell that NORTHUMBERLAND was coming.

At Toronto, NORTHUMBERLAND and DALHOUSIE CITY originally operated from the west side of the old Yonge Street slip. During the mid-1920s, Toronto's waterfront was extended out into the Bay by means of landfill operations and an entirely new set of piers was created. From 1927 onward, the N.S. & T. boats ran from the west side of the York Street slip, alongside the new Terminal Warehouse, which still exists today as part of the Harbourfront complex.

At Port Dalhousie, the boats would first moor facing inward on the east side of the harbour below Lock One of the canal. There they put ashore those passengers bound for Niagara Falls, for they could transfer directly to the company's electric cars which would take them to the Falls via the Grantham Division and Main Line of the N.S. & T. The steamers would then turn in the harbour and tie up, facing outward, on the west side wharf where they would unload passengers bound for Lakeside Park (which was located right beside the dock) and those who would board the "local" N.S. & T. cars for St. Catharines or other destinations in the immediate area. This procedure lasted through 1945, after which the radial cars to Niagara Falls were discontinued and the boats ceased to call on the east side of Port Dalhousie. Thereafter, passengers for the Falls were picked up by buses which pulled in at the dock on the west side of the harbour, the steamers still turning in the basin before docking so as to moor facing the lake at this berth.

The N.S. & T. steamers always took on their bunker coal at Toronto, and, like most of the local passenger boats, patronized the Century Coal Dock which, after the east end of the harbour was improved, was located south of the entrance to the Keating Channel, at Cherry and Villiers Streets. The coal was loaded by hand from two-wheeled carts which were rolled on board the steamers. When approaching the dock, the boats signalled their intent to bunker by blowing three long whistle blasts, and this signal was most impressive when blown by NORTHUMBERLAND, for the beautiful notes of her chime whistle would echo around the Bay. It was generally acknowledged that NORTHUMBERLAND had one of the most melodious whistles ever heard in Toronto harbour.

NORTHUMBERLAND and DALHOUSIE CITY regularly made two round trips each between Toronto and Port Dalhousie on weekdays, and often made three trips each on summer weekends when there would be heavy passenger traffic. The late evening trip on weekends would not arrive back in Toronto until the wee small hours of the morning, for it did not leave Port Dalhousie until about midnight.

The onset of the Great Depression hurt most of the passenger lines on the Great Lakes, and certainly took its toll on the service provided by the Niagara Navigation Division of Canada Steamship Lines. The effects of the Depression, however, did not greatly reduce traffic on the N.S. & T. boats, for they did not have to rely solely on the excursion trade. As well as offering good service to Niagara Falls via the connecting radial cars, the boats provided a quick mode of travel between the cities of Toronto and St. Catharines, and passenger travel held up well on the route even during the worst years of the Depression.

As the 1930s wore on, passenger traffic on the whole N.S. & T. rail system dropped off rather markedly, but the navigation company continued to do well. In the late 1930s, NORTHUMBERLAND'S steel deckhouse was given a major refurbishing to correct the deterioration that had set in over the years and which had undoubtedly begun back in the early years when it had been exposed to salt spray on the coast. It is said that the cabin had rusted away badly at the point where it joined the deck.

The N.S. & T. boats did not confine their service to the summer months as did many of the excursion lines on the lakes. They ran for the full period of navigation each year. In the off-season, service was generally limited to one round trip per day, operated out of Port Dalhousie rather than Toronto. Although NORTHUMBERLAND was the more expensive of the two boats to operate, because of her increased coal consumption, she frequently was the boat that provided the reduced service in the early spring and late fall. She had more freight space on her main deck than did DALHOUSIE CITY, and she was thus able to provide better service for shippers during periods of heavy freight movement. The freight carried often included work horses destined from Toronto to Niagara for work on the farms and orchards there, and in the autumn there would be large consignments of Niagara-grown fruit sent to the markets in Toronto. The fruit was generally shipped aboard the steamers in wagons, and it might thus be said that NORTHUMBERLAND was an early version of the R/Ro ship!

NORTHUMBERLAND and DALHOUSIE CITY did not often stray from their regular run, for traffic demanded that they stay within their designated schedule. During the Depression years, however, NORTHUMBERLAND was given some rather unusual duties. When the new Welland Canal opened for vessel traffic, it was a great tourist attraction, and the N.S. & T. set out to take advantage of that situation. When the canal was new, NORTHUMBERLAND would run short excursions from Port Dalhousie on which she would enter the new canal at Port Weller and proceed up through Lock One, and sometimes through Lock Two as well, and then turn around and make her way back to Port Dalhousie. These side trips could be taken by St. Catharines area residents, and also by those who had come over from Toronto on the boat and who, for a small extra fare, could purchase tickets for the canal cruise as an extension of their cross-lake excursion. These canal trips were very popular, and no doubt helped the company to offset any deleterious effects that the Depression had on its revenues.

Another unusual service that the boats offered was trips out of Hamilton for Port Dalhousie for special party groups. Should a sufficiently large group be available, one of the steamers would be sent over to Hamilton to pick up the party, bring it to Port Dalhousie, and then return it to Hamilton later in the day. Several such trips were operated each season.

Traffic on the Port Dalhousie route held up very well during the years of the Second World War, for people were happy to be able to take a lake trip and, for a few hours, to forget the worries which the great conflict normally caused them. By that time, the road network in Southern Ontario was reasonably well developed, but the restrictions on the availability of gasoline during the war forced many people to leave their automobiles at home, and the lake boats provided a pleasant alternative, particularly when the ever-popular Niagara Falls tourist area could be reached so easily via the ships and the connecting radial cars. The same rationale applied to the movements of commercial travellers between the cities of Toronto and St. Catharines. During the war years, NORTHUMBERLAND carried the familiar 'V for Victory insignia painted on her bows in red.

It has been reported that Canadian National offered to sell the combination of the cross-lake steamers and Lakeside Park in October of 1941, and that a prospective buyer appeared, but that the sale was never completed due to complications that arose in connection with the financing of the new venture. It is not known who the prospective purchaser was. The boats and the park were again offered for sale in one package in August of 1943, but no takers came forward and the N.S. & T. service carried on as before.

With the end of the war and gasoline rationing, passenger traffic began to drop off drastically, for the era of the automobile had truly arrived. After 1946, the navigation company sustained an operating deficit each season, but the service carried on. Thought was given to disposing of one of the ships and carrying on with only one steamer, but it was decided that such action would have disastrous effects on the combined operations of the navigation company and Lakeside Park through the disruption of the regular schedule that had been in effect for so many seasons. Nevertheless, the demise of one of the ships eventually became a reality, although it was not through the volition of the company that it occurred.

On the morning of Thursday, June 2nd, 1949, NORTHUMBERLAND was lying at her winter berth on the west side of Port Dalhousie harbour. She was facing inward and DALHOUSIE CITY lay ahead of her, further up along the wharf and around the knuckle. NORTHUMBERLAND had been freshly fitted out for the coming excursion season, and most of her crew were on board, for she was scheduled to start her summer service on the following day, Friday, June 3rd.

Sometime around 6:00 a.m. on June 2nd, fire broke out in or near a washroom on the ship. A stewardess, Anna Buchholz, was awakened by the smoke and she sounded the alarm. Chief Engineer A. J. Burton mustered the crew and formed a fire brigade, but these efforts were of no avail as the fire spread rapidly throughout the vessel. The Port Dalhousie volunteer fire brigade and the St. Catharines Fire Department were summoned to the scene, but they also were unable to extinguish the fire until NORTHUMBERLAND was completely gutted. The water which was poured onto the steamer during the fire caused her to settle lower in the water, but she did not sink, and took on only a bit of a list to starboard (toward the dock).

An investigation into the cause of the fire failed to yield any conclusive results, although various reports suggested that the cause was either carelessly discarded smoking materials or a defect in the ship's electrical wiring. It was alleged that some difficulties with the electrical system had been encountered during the fitting out of NORTHUMBERLAND. The value of the loss was assessed in the $200,000 - $250,000 range, but this could hardly have been considered to be the full value of the ship in operating condition.

NORTHUMBERLAND was damaged to such an extent that repairs could not be carried out economically, and Canadian National had long discouraged large capital investments by any of its subsidiaries. Accordingly, in September of 1949, the hull of NORTHUMBERLAND was sold for scrap, and it was decided that she would be broken up at Port Weller Dry Docks. She was towed over to Port Weller and, for a time, the gutted hull was moored along the south side of the Lakeshore Road between the "bridge at Lock One and the shipyard. In due course, NORTHUMBERLAND was moved into the drydock and there her last remains were quickly dismantled.

Needless to say, the N.S. & T. and its long-time passengers were put into a state of shock by the loss of NORTHUMBERLAND. The company was unwilling to throw in the towel, however, and it completed the 1949 season with only DALHOUSIE CITY in service. Traffic had dropped off to such an extent that purchase of a replacement for NORTHUMBERLAND was out of the question. Even the Canada Steamship Lines service to the Niagara River was suffering and its once-large fleet of steamers had dwindled to the point that, since the mid-thirties, only CAYUGA had remained in service.

The N.S. & T. found that operation with only one boat was not satisfactory, and consideration was given to the complete abandonment of the service. The company's mind was made up for it when, early in 1950, the federal government imposed strict new fire regulations for passenger boats as a result of the destruction by fire of the C.S.L. steamer NORONIC at her Toronto pier on September 17, 1949. It was economically unfeasible to consider altering DALHOUSIE CITY to make her conform to the new regulations and accordingly, early in 1950, she was sold to a Montreal firm which used her in the excursion business there as (b) ISLAND KING II. She was destroyed by fire ten years later, whilst laid up for the winter, and under very peculiar circumstances.

Thus ended one of Lake Ontario's best known passenger services. It was unfortunate in the extreme that NORTHUMBERLAND should go out under such unexpected circumstances, and that her demise should have proven to be one of the major factors in the undoing of the N.S. & T. services. But a portion of this beautiful and popular steamer still lives on at Toronto. When NORTHUMBERLAND was scrapped, her melodious chime whistle was acquired by Harold Dixon, the proprietor of the Toronto Dry Dock Company and an inveterate collector of memorabilia from Toronto's most famous ships. It is believed that the whistle was used briefly aboard his tug H.J.D. NO. 1, and it certainly was used for a number of years on the tug J. C. STEWART. When the Dry Dock Company went out of business in the early 1960s and J. C. STEWART was scrapped, the famous whistle passed to the collection of the Marine Museum of Upper Canada, where it can still be seen. In fact, it can even be heard on occasion when hooked up to the museum's air system, although the tone that it now emits is only a whisper of what it could produce on 160 pounds of steam from NORTHUMBERLAND's boilers. The whistle was even used a few years ago to signal the start of construction on the Welland Bypass section of the Welland Canal, it being considered that the whistle had special significance for the Niagara Peninsula area.

Ed Note: Of great assistance in the preparation of this special feature were the writings and personal reminiscences of NORTHUMBERLAND by T.M.H.S. Secretary, J. H. Bascom. Those wishing to learn more about the various operations of the N.S. & T. would do well to read Niagara. St. Catharines and Toronto, by John M. Mills, published jointly by the Upper Canada Railway Society and the Ontario Electric Railway Historical Association in 1967.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.