Table of Contents

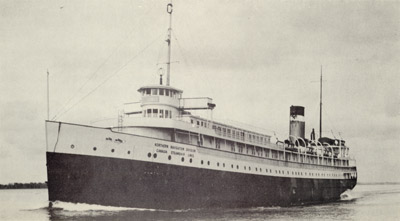

It is hard to imagine that there could be even one reader of these lines who has not heard of the lake passenger steamer HAMONIC. She is considered by many to have been the most graceful and well-proportioned vessel of her type ever built and she was certainly popular amongst ship photographers of her era.

The story and photographs of her building at Collingwood in 1908 have been published elsewhere and almost everyone knows of her destruction by fire at the Point Edward terminal on July 17th, 1945. Not many would know that she came very near foundering in Lake Superior in 1925 when she threw her propeller during a violent gale.

HAMONIC, phtographed by Capt. Wm. J. Taylor, is seen downbound on a late-season trip with a full load of flour.

The following account is reprinted from the September 1937 issue of "U.S. Steel News", house organ of U.S. Steel and the Pittsburgh Steamship Company.

"The wind was 55 miles an hour, and the seas were sweeping over us." Thus wrote the late Captain George H. Banker in his log, in describing the violence of a Lake Superior storm when he maneuvered the Pittsburgh Steamship Co. steamer RICHARD TRIMBLE to rescue the Canadian passenger steamship HAMONIC of the Northern Navigation Co. Ltd.

It was November 6, 1925, and the HAMONIC was being tossed about in the trough of the sea. It was difficult enough for Captain Banker to navigate his own ship without thinking of adding a tow.

The TRIMBLE had passed out of Whitefish Bay into Lake Superior the night before in a heavy northwest gale. At 11:00 p.m., when she was about 75 or 80 miles above Whitefish, the wind blew the vessel around, and the captain started her back for Whitefish Point under check. It was then that she first caught sight of the HAMONIC, but we shall let the captain's log tell the story.

"We ran only a few minutes when we saw the HAMONIC, which we had previously seen in the trough of the sea, blowing distress signals and showing a red flare light. When we saw the signals of distress, we changed our course over toward him and went down across his stern about 300 ft. away - this was about 1:30 a.m. Someone on board the HAMONIC sang out that their wheel was gone......

"At the time I went under the HAMONIC's stern ... the sea was washing all over us. It was an awful sea and blowing a gale from the Northwest, The wind varied from West to Northwest to West Northwest. We could do nothing in the night. It was snowing hard and for a while I could not see him. I could not hear anything in the pilothouse on account of the wind. I checked down to stay as near to him as possible and went at various speeds down before the wind, thinking to get back to him sometime before daylight.

"At 7:00 a.m. I turned around head into the wind. It was still snowing. I went back looking for the HAMONIC. Located him about 9:45 a.m., and at 10:30 a.m. went across his bow close to him and sang out for him to get his towline ready and we would try to pick him up,

"The Captain called out 'all right'. The wind was 55 miles an hour and the seas were sweeping over us. The seas seemed bigger than they had been. When we would turn, we would roll our decks under.

"We went down before the wind and turned around and went up to windward of him about two miles and turned again and came down close to his bow. He was lying in the trough of the sea heading about North Northeast. The wind was then from about the North Northwest. We went through the maneuver three times before we could get his line. He put out about 300 ft. of 3/4--inch line with a life preserver on the end, which floated dead to windward of his bow. This made the operation very dangerous. We had to pass within about 25 ft. of his bow to get the line. Our men about midships finally got hold of the line with grappling hooks and pulled it on deck. At about the same time one of our men forward got a heaving line to the HAMONIC over her bow. But seeing that the 3/4--inch messenger was the best, we hauled in the heaving line and hauled the HAMONIC's towline on board by means of the 3/4-inch messenger.

"The towline was a 10-inch line. I held the stern of the TRIMBLE as best I could about 75 or 100 ft. from the bow of the HAMONIC while we made the towline fast. The towline led from his bow to our stern chock. Seas were coming over our stern and the men were in constant danger from these seas. Even after we got the line the seas came right over our stern. After we got the line made fast we had to maneuver very carefully because both vessels were jumping and rolling very heavily. We had squalls of snow right along and the weather was very cold. Our thermometer was washed overboard from the front of our observation cabin and we were all covered with ice. The HAMONIC put out about 500 ft. of towline and we got him down abreast Whitefish Point at 6:21 p.m. November 6. At the time we passed Whitefish, the wind was about 30 miles per hour from the West and increasing. At the time we got to Iroquois, at about 9:00 p.m., the wind had increased to about 35 or 40 miles per hour from the Southwest and was increasing.

"We left the HAMONIC at Iroquois Point. He anchored there .... The towline was let go by us after the second mate called up over the phone that the HAMONIC had let go her anchor.

"The only talk I had with the Captain of the HAMONIC was when I told him to have his towline ready and I saw him standing on his bridge in a big fur coat and he replied 'all right'. That was just before we started to pick up the HAMONIC.

"We had water in the TRIMBLE until she was drawing about 19 ft. aft and about 13 ft. 6 in. for'd.

"Practically our entire time from 2 a.m. to 9 p.m. November 6 was devoted to the HAMONIC. I was 48 hours without sleep and for 30 hours I didn't even have a meal.

"The topworks of the HAMONIC were badly battered and I later heard at the Soo, on the way down, that she was badly smashed up. She was rolling so hard that it would make you sick to look at her and they could hardly walk on her decks."

(Ed. Note: RICHARD TRIMBLE still serves the U.S. Steel fleet. She is a 580-footer built in 1913 at Lorain by American Ship.)

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.