Table of Contents

We usually try to vary the types of ships featured from month to month in these pages so that the articles will not be repetitive and the interest of our members will be maintained. Our choice of a Ship of the Month for this issue, however, follows naturally in the wake of BENMAPLE, whose story was featured in December. Not only was AYCLIFFE HALL lost by collision, as was BENMAPLE, but the accident that claimed her half a century ago occurred in the same year as the loss of BENMAPLE.

It also occurred to us that AYCLIFFE HALL was a most appropriate ship to feature at the time when the old Hall Corporation fleet is finally being broken up. In 1986, the last six Halco tankers were spun off to Enerchem Transport, and the Royal Bank of Canada, as receiver of Halco, contracted the management of the remaining bulk carriers out to Navican Management Inc. The disposal of the Halco bulkers by the Royal Bank seems to be inevitable, and thus may soon be written the final chapter in the history of a fleet which, for many years, has been one of the most familiar on the lakes and the St. Lawrence River. It operated on both sides of the border, had affiliations with several of the industries for which it hauled cargoes, and was involved with such famous lake shipping entrepreneurs as James Playfair.

The Hall organization had long been involved in the operation and ownership of vessels by the time the 1920s, the real "Era of the Canaller", came along, and it would take far more space than we have available here to even begin to trace the history of the Hall fleet to that point in time. Suffice it to say that, by 1926, the Hall Corporation of Canada had a large fleet of ships of varying types and ages, and all of them were canal boats, for the company had not yet expanded into the upper lakes trades.

Over the winter of 1926-1927, the Hall Corporation disposed of most of its steamers to Canada Steamship Lines, and set about building a new and much more modern fleet. Hall let to the Smith's Dock Company Ltd., of South Bank-on-Tees, England, contracts for a total of ten canal-sized steamers, and in partial payment for the new hulls, Hall turned over to Smith's Dock Company for scrapping the 1912-built "Pre-Lakers" ROBERT M. THOMPSON and RUBY, which Hall had acquired in 1924.

The first three new canallers were ordered in 1926 and delivered in 1927, these being WALTER B. REYNOLDS (II), JOHN H. PRICE and MONT LOUIS, which were almost exact sisterships. The second contract was let in 1927, and produced five sistership steamers which were delivered in 1928, namely AYCLIFFE HALL, CONISCLIFFE HALL (I), EAGLESCLIFFE HALL (I), WESTCLIFFE HALL (I) and ROCKCLIFFE HALL (I), as well as two more, MEADCLIFFE HALL and GEORGE L. EATON (II), which were delivered in 1929. The seven latter vessels differed rather substantially from the first three, not only in cabin arrangement but also in the fact that the first group had stepped decks (in the manner of many British-built canallers of the early-to-mid-1920s), while the latter group did not and boasted a slightly greater cargo capacity.

AYCLIFFE HALL was the first of the second group of canallers to be built and was Hull 845 of the Smith's Dock yard. Her steel hull was 253.0 feet long (258.5 feet overall), 44.1 feet in the beam, and 18.5 feet in depth, giving her tonnage of 1900 Gross and 1204 Net. She was powered by a triple expansion engine, which had cylinders of 15, 25 and 40 inches diameter, and a stroke of 33 inches; the engine's Indicated Horsepower was variously reported as 750 or 800. Steam at 180 p.s.i. was produced by two coal-fired, single-ended, Scotch boilers which measured 10'6" by 11'. All of the machinery was built for the vessel by the shipyard and was standard to all ships in the order.

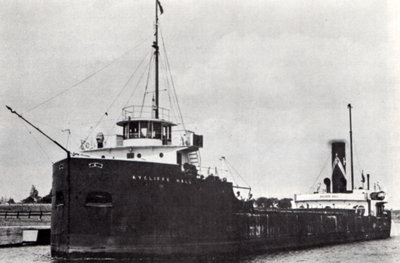

Photo by George Deno shows AYCLIFFE HALL upbound in the Galops Canal.

AYCLIFFE HALL was enrolled at Montreal as C.147800. Her keel was laid on Sunday, January 15, 1928; the laying of a keel on Sunday was unusual, but no doubt was a consequence of the need to complete the ships of the Hall order without delay. AYCLIFFE HALL was launched into the waters of the River Tees on Thursday, March 22, and she ran trials on Wednesday, April 11. She was ready to sail for Canada shortly thereafter, and we shall describe more fully her unusual delivery voyage later in our narrative.

AYCLIFFE HALL was not only the first boat of her class in the Hall Corporation fleet, but she also began its name series that has persisted to this day, in that she was the first of the company's ships to carry a "Cliffe Hall name. The vessel was named for the town of Aycliffe in Durham County, England, which was the birthplace of Albert Hutchinson, who had been associated with the Hall interests for many years and was appointed manager of the Hall Corporation of Canada in 1927. Aycliffe is located just a few miles inland from Middlesbrough (South Bank) on the Tees where the ship was built, and it was Hutchinson's involvement with the Middlesbrough area that led to the letting of the contracts for the ten canallers to the Smith's Dock. Hutchinson served as manager, president and board chairman of the Hall Corporation over the years, and was still active at the time of his death in 1952.

The unusual name given to the steamer not only honoured Hutchinson's home, but also involved, undoubtedly, a bit of bragging about the position that the fleet enjoyed with the commissioning of its new canallers. As additional boats were constructed, the "Cliffe" part of the name of the first ship became part of the suffix as well, and there seems no reason for it except that the company's executive must have liked the look and sound of it. It certainly could never be said that the names chosen for the various Hall vessels were not distinctive!

Likewise distinctive was the appearance of AYCLIFFE HALL and her sisters. In Ye Ed's humble opinion, they were amongst the best looking of all of the canallers built in the 1920s, when British yards were turning out such vessels like sausages from a butcher's shop. The seven Hall boats, together with sisterships FULTON and SOUTHTON built for the Mathews fleet, as well as the Tree Line's TEAKBAY and the Foote Transit Company's F. V. MASSEY, were sturdy and substantial in design, but at the same time were pleasing to the eye, with several "extra" features that did not appear in the many utilitarian canallers with their spartan accommodations and "short-cut" lines.

AYCLIFFE HALL had a virtually sheerless hull (as did most canallers of the period), with bluff bows, a straight stem, and a heavy but pleasing counter stern. She carried a full raised forecastle, with a closed rail protecting much of the forecastle head, and her anchors were placed far forward, housed in round-topped pockets cut into the forecastle just above the level of the spar deck. Her name appeared in small white letters, high up on the black forecastle, and the letters leaned markedly toward the bow, no doubt to give the appearance of speed (a virtue not possessed by many canallers).

On the forecastle head was set the wide but rather shallow texas cabin which contained the master's bedroom and office, the rest of deck crew and the mates being accommodated in the forecastle. Three portholes were cut into the forward bulkhead of the texas, and at its centre were displayed her builder's plate and bell. The bridge deck above featured flying navigation wings supported on closed struts tastefully incorporated into the sides of the texas, and the front of the bridge deck was curved outward into a gentle bow to provide additional deck space in front of the pilothouse.

The round-fronted pilothouse sat as far back on the bridge deck as possible, and featured five very large windows in its front, which gave excellent visibility, especially when canalling. A broad sunvisor kept the sun out of the eyes of those on watch. An open rail ran around the monkey's island on the pilothouse roof, but no navigation was done from there. Large freshwater tanks were located on the bridge deck on either side of the pilothouse, and on the open rail across the front of the bridge was often hung a white canvas weathercloth on which the ship's name was prominently displayed. A framework was provided on which could be hung awnings to shade the entire bridge deck on hot summer days.

The steamer's quarterdeck was flush with the spar deck, and a closed steel bulwark ran around the stern to shelter the cabin located there. The ship's name was painted in large white letters at the forward end of this rail, beside the boilerhouse. The after cabin itself was a large structure which accommodated the engineroom officers and crew, and the stewards and galley staff, and also contained the officers' and crew's messrooms. The boat deck overhung the sides of the cabin all the way around to give some shelter from the elements, and this was a feature which only very few canallers boasted. Two lifeboats were carried on the boat deck, and from it also rose the tall and fairly heavy but unraked stack, on either side of which were two water tanks. Two large ventilator cowls stood directly ahead of the stack. The coal bunker hatch was set far forward on the boat deck, and around it ran an open rail, on which was sometimes hung a white canvas weathercloth which, like the one on the bridge deck, proudly displayed the steamer's name.

AYCLIFFE HALL had six large hatches set into her spar deck for access to the two cargo holds. The sixth hatch was particularly large and was raised above the deck. There were six steam winches for the mooring lines and a steam windlass as well. In some of AYCLIFFE HALL's sisterships, these winches would be used to handle the cargo booms and hoisting cables, but AYCLIFFE HALL was not equipped with any such gear. She carried only two pole masts, one set just abaft the forward cabin, rising right out of the spar deck, and the mainmast stepped well aft, abaft the funnel. At no time did she carry kingposts or cargo booms. In this respect, she resembled EAGLESCLIFFE HALL, ROCKCLIFFE HALL and WESTCLIFFE HALL, all of which had a similar mast arrangement. On the other hand, CONISCLIFFE HALL, MEADCLIFFE HALL and GEORGE L. EATON all carried a cargo boom on a heavier foremast, and the mainmast, set part way down the deck, carried two more booms. EAGLESCLIFFE, ROCKCLIFFE and WESTCLIFFE HALL were later retrofitted in a similar manner to allow them to handle some of their own cargoes, particularly pulpwood, but AYCLIFFE HALL was not to last long enough for her owners to refit her in this manner.

AYCLIFFE HALL was painted in the normal plain but distinctive Hall livery. Her hull and forecastle, and all of the closed bulwarks, were painted black, while the cabins were white. The frames of the large pilothouse windows were of wood and were varnished. The foremast was a dark buff shade and the mainmast was black. The stack was black, with the familiar white 'H' and "wishbone" design.

The trials run by AYCLIFFE HALL were obviously successful, for on Tuesday, April 17, 1928, she sailed from Middlesbrough with a cargo of 2,200 tons of fluorspar consigned to the Algoma Steel Corporation at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. As well, on her delivery voyage across the Atlantic, AYCLIFFE HALL carried on her deck the 65-foot steel tug VIGILANT (I), which had been built in Holland in 1906 and transferred to British registry in 1908. The tug had been bought by Mont Louis Seigniory Ltee., Montreal, for the purpose of towing logs at Mont Louis, Quebec. The Mont Louis Seigniory Ltee. was an Augsbury family enterprise, so it was not surprising that it was from Mont Louis that the Hall canallers carried most of the pulpwood that formed so many of their upbound cargoes. Mont Louis is located on the shore of the Gaspe Peninsula, on the south side of the St. Lawrence River. At one time, the port featured a large flume-fed trestle with chutes, from which pulpwood was loaded aboard the many steamers that called there.

AYCLIFFE HALL crossed the North Atlantic in safety and stopped at Sorel, where she was moored at the Dominion Government wharf. The sheer legs on the dock were used to lift VIGILANT from AYCLIFFE HALL's deck, whereupon the steamer was moved ahead up the pier and the tug was lowered into the water. AYCLIFFE HALL reached Montreal on Wednesday, May 16, 1928, exactly ten days after the launch of ROCKCLIFFE HALL, the last of the five Hall sisterships built in 1928. The fact that all five steamers went into the River Tees between March 22 and May 6 gives some indication of the speed with which these vessels were constructed. In any event, AYCLIFFE HALL delivered her fluorspar cargo to Sault Ste. Marie, and then went into regular service, carrying innumerable loads of grain, coal and pulpwood.

AYCLIFFE HALL and her six sisterships enjoyed fairly uneventful lives, except, of course, for the untimely loss of AYCLIFFE HALL, herself, in her ninth season of operation. The others all survived until the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, and served both the Hall fleet and the Misener interests (to whom all six were sold in 1954) without major incident. The only serious problem to affect any of them involved EAGLESCLIFFE HALL during her first year, 1928. Crossing Lake Erie in heavy weather, she began to break apart and it was only by securing mooring cables along her deck to strap her together that she was able to make port at Buffalo. There she was drydocked and permanent repairs were made. The incident does not appear to have indicated any weakness in the design of the sisterships, for EAGLESCLIFFE HALL never suffered a repetition of the problem, nor did any of the other sisters ever fall victim to similar difficulties.

A late-season view caught AYCLIFFE HALL and CYCLO-WARRIOR fighting their way through ice in the Lachine Canal.

In the autumn of 1931. AYCLIFFE HALL was delayed whilst downbound with a cargo of grain. A report in "The Evening Telegram", Toronto, dated November 8, 1931. stated that "low water in the St. Lawrence River above Montreal is delaying the downward progress of thirteen vessels tied up near Cardinal, Ontario, at the western entrance to the Galops Canal. Most of the boats are carrying grain for Montreal, Sorel or Quebec, but a number are oil tankers or laden with general cargo. The MOSNA, RAHANE and HENNESEID have been halted at Cardinal since Tuesday (Nov. 3), while the following were held up today: SIMCOLITE, ROYALITE, WEYBURN, ZENDA, CANADIAN BEAVER, AYCLIFFE HALL, ELGIN, SIMCOE, MAPLETON and ACADIAN. Thirteen feet is the permissable [sic] draft of craft in the canal system. It was reported that a further reduction (in allowed draft) might have to be made should conditions not improve."

Then, in the autumn of 1934, another report in the same paper mentioned AYCLIFFE HALL. Datelined October 30, Goderich, it stated that "near-calm again prevails on Lake Huron tonight, after a three-day storm, and vessels again are on the move. The JOSEPH P. BURKE put into port at noon today with a storage cargo of wheat, the first of the season. She took 108 hours to make the trip from the head of the lakes, usually made in 48 hours. She finally put into Harbor Beach, Michigan, where she lay at anchor until the blow was over. Tonight, the tanker IOCOLITE of the Imperial Oil fleet arrived with a cargo of gasoline... The AYCLIFFE HALL, GEORGE L. EATON and SUPERIOR are expected here during the night from Harbor Beach, where they (also) took shelter..."

Two winter lay-up seasons were eventful for AYCLIFFE HALL. She spent the winter of 1931-1932 frozen in the ice at Cote St. Paul on the St. Lawrence River, rather than safe in some port with a storage cargo, but no damage seems to have been suffered by the ship as a result of this escapade. Then, on December 2, 1934, she loaded a cargo of corn at Prescott and took it all the way (!) to Cardinal where she laid up, a most unusual trip indeed.

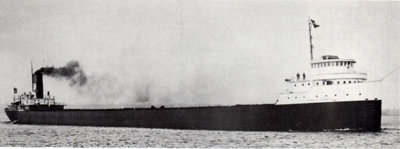

AYCLIFFE HALL is seen in Port Colborne harbour, heading out on Lake Erie.

The happy life of AYCLIFFE HALL, however, was to be shattered in the early morning hours of Thursday, June 11, 1936. Upbound light, presumably to load grain at the Lakehead, AYCLIFFE HALL passed up the Cardinal Canal at 1:50 p.m. on June 9. She was up through Lock One at Port Weller at 3:10 p.m. on June 10, and she was reported upbound at Port Colborne at 9:38 p.m. that evening, a very fast canal passage indeed. Once out on Lake Erie, however, AYCLIFFE HALL did not make nearly such good time, for visibility on the lake was reduced by a dense fog. At the time, the steamer was commanded by Capt. Ross Sinclair of Toronto, and her chief engineer was A. Mackintosh. As a result of the fog, Capt. Sinclair reduced the ship's speed, and by about 5:00 a.m. on June 11th, AYCLIFFE HALL was some twelve miles southwest of Long Point. Had her officers known the peril that lay in wait for their ship, they undoubtedly would have checked her speed even further, or perhaps gone to anchor somewhere to await more favourable conditions.

Meanwhile, in the same area of Lake Erie was the big American bulk carrier EDWARD J. BERWIND (63), (b) MATTHEW ANDREWS (III)(74), (c) BLANCHE HINDMAN (III)(79), (d) LAC STE-ANNE, 595.6 feet long and 8318 Gross Tons, built in 1924 at Ecorse, Michigan. Owned by the Franklin Steamship Company and operated by the Bethlehem Transportation Company, the BERWIND was under the command of Capt. George Brock, and was downbound from Ashland, Wisconsin, with a cargo of iron ore for the Bethlehem Steel plant at Lackawanna, N.Y.

Suddenly, those on watch in the pilothouse of each freighter saw the other vessel loom out of the fog directly ahead. An exchange of warning whistles followed, but all to no avail as the BERWIND's bow knifed into the aft port side of AYCLIFFE HALL near the boilers. A canaller's hull simply could not withstand an impact of this nature, and AYCLIFFE HALL rapidly began to fill with water. The BERWIND lowered her lifeboats immediately and all nineteen persons from AYCLIFFE HALL were safely brought to the larger steamer. The Hall canaller, however, was mortally wounded, and she soon foundered in 72 feet of water.

Photo by Young, dated 1924, has EDWARD J. BERWIND downbound at Little Rapids Cut in the St. Mary's River.

Two other ships soon arrived on the accident scene. The Cleveland-Cliffs steamer JOLIET answered a radio distress call (presumably sent by the BERWIND), but she arrived at the site after AYCLIFFE HALL's crew had been rescued, and she found nothing on the water but a field of wreckage. On the scene almost immediately after the collision was the Imperial Oil tanker WINDSOLITE, under the command of Capt. Charles R. Dyon. WINDSOLITE did not have radio, but her crew had heard the warning whistles of the BERWIND and AYCLIFFE HALL. By the time the tanker reached the scene, AYCLIFFE HALL was already gone and only wreckage could be seen. WINDSOLITE tried to pull alongside the BERWIND, but the latter's officers warned her off, as the BERWIND at the time was involved in pulling aboard the men in the lifeboats, and it was feared that the approach of WINDSOLITE might endanger the operation. The tanker did take on board a lifeboat which had floated free of the sinking canaller, but which was empty of persons and half-full of water. WINDSOLITE dropped the boat on a wharf at Port Colborne as she headed down the Welland Canal later that day.

The survivors of AYCLIFFE HALL were taken by the almost undamaged BERWIND to Buffalo, where they were put ashore "after due questioning by United States immigration officials". (We are certain that the men were hardly in the mood for such interrogation after their ordeal, but officials will be officials, and it matters not how one crosses the border - Ed.) "Thank God they were all saved" was the comment made to the press by Albert Hutchinson of the Hall Corporation upon hearing of the accident.

Throughout the summer of 1936, the disposition of the wreck of AYCLIFFE HALL was much in the minds of all concerned, for the vessel was a menace to navigation where she lay. The Dominion Government insisted that the wreck be removed in such a manner as to provide minimum clearance of 53 feet (remember that the ship sank in only 72 feet of water) and that, until such removal were effected, appropriate day and night signals were to be maintained over the wreck. In due course of time, a salvage contract was let (presumably by the Insurers) to Sin-Mac Lines Ltd., Montreal, who dispatched the tug CHAMPLAIN, the wrecker MAPLECOURT, and a number of pontoons to the site. The following report appeared in "The Toronto Star" in early September of 1936.

The Sin-Mac wrecker MAPLECOURT, which worked on AYCLIFFE HALL, is seen assisting the grounded steamer W.D.CALVERLEY JR.

"On board Salvage Ship MAPLECOURT, off Long Point, Lake Erie, September 2nd -The 2,000 ton freighter AYCLIFFE HALL was brought from her bed on the muddy bottom of Lake Erie, 22 miles off shore, late yesterday afternoon after two months of preparation which will write a new page in the history of fresh water salvaging. Early last June, the AYCLIFFE HALL and the U.S. freighter EDWARD J. BERWIND collided in heavy fog, twelve miles off Long Point, sending the Canadian craft to the bottom, with the plates on the port side of her aft hold ripped open. No lives were lost.

"From dawn yesterday, the crew of the salvage ship MAPLECOURT, and divers Jeffrey Skinner and Roy Perkins, directed by Capt. Tom Reid, worked feverishly during the first long-awaited weather to connect air lines to the tanks and compartments of the sunken ship, 72 feet below the surface. Shortly after noon, a maelstrom of bubbles above her resting spot heralded the rising of the ship, as compressed air forced the water from her forepeak and forward tanks. For five hours, pumps on the deck of MAPLECOURT shot hundreds of thousands of cubic feet of compressed air into the AYCLIFFE HALL's compartments.

"At sunset, the foremast, which had been a few inches above water, trembled and rose a foot or two, then the entire fore part of the ship rushed to the surface, churning the lake into a smother of foam and bubbles, the waters pouring in cascades from her foredeck and wheelhouse. As the bow rose above the surface, success for a venture which has occupied nearly two months seemed assured. Today, four pontoons, which have been secured to the stern, will be blown out, sufficiently lightening the ship to bring her into shoal waters eight miles from shore, where her remaining compartments will be pumped out, preparatory to being brought into harbour for repairs.

"The AYCLIFFE HALL had settled on an even keel, the tip of her foremast remaining above the surface. A salvage crew under the veteran Great Lakes wrecker, Capt. T. Reid, took on the job of removing AYCLIFFE HALL on July 5, the original plan being to dynamite her upper structure, leaving fifty feet of clear water between the boat and the surface, in compliance with marine regulations. After considering the reports made by his two divers, who explored the sunken craft, Capt. Reid decided to float her by pumping air into the forepeak, water tanks and boilers, and four 3,800 cubic foot pontoons fastened to the stern of the ship... 'Until I saw her bow break the surface today, I could not be sure if the plan would work', Capt. Reid confessed as he barked orders from the deck of the MAPLECOURT yesterday evening. 'If I had been wrong, I would have been called crazy; but it worked, so I have the laugh now.'

"Added to the uncertain possibilities of the job have been two months of capricious weather which has whipped up the lake time after time to halt diving operations for a week or more. Working sometimes as little as three hours a day, the divers have removed the winches, anchors, anchor chains, and other loose machinery from the decks, reinforced the midship bulkhead with 30-foot timbers, covered the three hatches of the forward cargo hold with tarpaulins battened down with heavy hatch bars, and sealed up all spaces to be pumped out. Four pontoons were sunk beside the AYCLIFFE HALL's stern and held in place with anchor chains passed under the keel. Water pumps have been installed to pump out the number one cargo hold, the number two starboard and port tanks, and stern tanks. Working at this depth, men withstand a pressure of 45 pounds to the square inch. It was believed the AYCLIFFE HALL would come to the surface with the air pumped into her... but the pontoons were used to stabilize her and prevent a 'roll over' during the raising process or while she is being towed 22 miles to Port Burwell.

"From the time the divers first groped their way through AYCLIFFE HALL's murky holds and cabins, trouble dogged the efforts of the crew to get the hulk ashore before seasonal winds put a stop to their work this year. The dead calm which is needed to facilitate the handling of divers has occurred infrequently, leaving MAPLECOURT pulling restlessly at her anchors while precious time was spent in complete inactivity. Soon after the arrival of the pontoons, two of the huge boxes broke loose in heavy seas, sending the tug CHAMPLAIN, which is assisting the salvage ship, scouring the end of the lake for them. They were retrieved 24 hours later..."

Also working on the wreck of the AYCLIFFE HALL was the Sin-Mac tug CHAMPLAIN, seen here in a photo by Capt. William J. Taylor.

We have quoted nearly the entire "Star" story in view of the details which it gives concerning the operation, and also because its forecast of success for the raising of AYCLIFFE HALL was somewhat premature. True, the ship's bow was brought to the surface not once but twice, and there are several photos of the forecastle and pilothouse clear of the lake surface, but Tom Reid was unable to get the boat's stern up far enough for her to be taken into shallow water. Before long, autumn's inclement weather set in and Tom Reid, forced to admit defeat in his venture, pulled the Sin-Mac salvage crew from the scene. He had bid $30,000 for the job and it was one of the few salvage contracts he took on over the years that did not prove successful. CHAMPLAIN later brought Reid's pontoons to Toronto, and for years they lay near the east end of the south pier of the Western Gap.

The wreck of AYCLIFFE HALL remained on the bottom of Lake Erie, with the Dominion Government greatly concerned about the danger which it posed to navigation, although there is little doubt that the superstructure of the ship was scraped down by the lake ice in succeeding winters. On Monday, July 10, 1939. the Toronto press reported that "the AYCLIFFE HALL, sunk... off Long Point in collision with the EDWARD J. BERWIND, is believed to be responsible for the rub felt by the ALGOCEN on Saturday as she was coming past the Point bound for Port Colborne. 'No damage was done to the ALGOCEN*, said Capt. M. A. Livingstone, 'but the compass needle twirled around, indicating iron, and the rub was distinct enough to be felt by everybody on board. A man was even wakened from his sleep by the concussion.'"

On July 18, 1939, the hull of AYCLIFFE HALL was located in twelve fathoms of water by divers from U.S.C.G. CROCUS. The Canadian Department of Transport buoy tender GRENVILLE attended at the scene and used explosives to level the wreck so that it would not interfere with passing shipping. Thus ended any possibility of the ship ever being raised, either for reconstruction or for scrapping. It is interesting to note that in the spring of 1986, the remains of LAC STE-ANNE, the former EDWARD J. BERWIND, were being cut up for scrap in Port Colborne harbour, only a few hours' sailing time from the spot where she put an end to the career of AYCLIFFE HALL.

Ed. Note: The press reports quoted herewith are taken from the scrapbooks of the late James M. Kidd. Other material has come from various issues of "Canadian Railway and Marine World". Anyone interested in the detailed history of the Hall Corporation would do well to read The Wishbone Fleet, by T.M.H.S. member Daniel C. McCormick, 1972.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.