Table of Contents

Never before in these pages have we presented the story of a ship specifically designed and built as a sandsucker and since there have been a number of such vessels active on the Great Lakes over the years, we thought it to be about time that we featured a sandsucker. We were inspired by the recently received word of the imminent demise of CHARLES DICK which made us think back to an earlier unit of the fleet of National Sand and Material Company Ltd., the steamer SAND MERCHANT. This vessel is the fitting subject for an in-depth look at this time as 1977 brings with it the fortieth anniversary of her tragic loss in an accident which remains to this day one of the unexplained mysteries of the lakes.

The steel-hulled sandsucker SAND MERCHANT (C.153443) was

built at Collingwood, Ontario, by the Collingwood Shipbuilding Company Ltd. in 1927 for the

Interlake Transportation Company Ltd., (Mapes and Fredon), Montreal. Her keel was laid on April

28th, 1927 and on September 7th she was delivered to her owners. The chief dimensions of the

new vessel were as follows: length overall, 259.75 feet; length between perpendiculars, 252.0

feet; moulded breadth, 43.5 feet; moulded depth, 20.0 feet; deadweight on old Welland Canal

draft of 14 feet, approximately 2,300 tons; Gross Tonnage, 1981; Net Tonnage, 752.

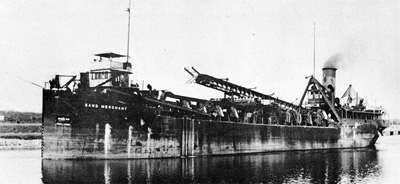

This is SAND MERCHANT as she appeared at the time of her loss. Photo from the collection of Capt. John Leonard shows her upbound in the Galops section of the Williamsburg Canal, St. Lawrence River.

SAND MERCHANT was propelled by a triple-expansion, surface condensing engine with cylinders of 15/2, 26 and 44-inch diameter and a stroke of 26 inches. Steam was supplied by two coal-burning Scotch type marine boilers measuring 13 feet by 11 feet, with natural draft and a working pressure of 200 lbs. On her trials which were conducted on September 1st, 1927, a mean speed of 10.42 knots was maintained on a draft of 7'9" forward and 12'8" aft.

The new steamer was a single-deck type vessel with sunken forecastle and a raised quarterdeck and she was fitted with six transverse watertight bulkheads. Cargo was carried in two open, hopper-sided holds. When SAND MERCHANT was loading, sand or gravel was pumped from the bottom of the lake through 18-inch diameter pipes by two 18-inch centrifugal pumps. The material thus brought aboard was discharged into double steel troughs running down each side of the deck and arranged one over the other. By means of various sizes of screens and cover plates, sand or any desired size of gravel could be screened out and discharged into the holds. The residue was flushed over the side and back into the lake by means of spillways.

As SAND MERCHANT was originally constructed, cargo was unloaded from the holds by means of two swinging, stiff-legged derricks, each one equipped with a two-yard grab bucket. One derrick was mounted aft of the forecastle while the second was placed in front of the stack. In 1930, certain changes were made in the unloading equipment. The derricks were removed and in their place was fitted an elevator system and a conveyor belt discharge to the dock over a swinging boom. The unloading boom was hinged aft and was suspended from a large A-frame mounted immediately forward of the funnel.

SAND MERCHANT was a very substantial-looking canaller. Forward, she carried a large, square pilothouse atop a texas cabin that was almost hidden by the assorted machinery carried on the forecastle. The pilothouse had a somewhat bare appearance in that it was not equipped with a sunvisor. The ship was frequently navigated from an open bridge located atop the pilothouse, surrounded by a canvas dodger and topped by a protective awning. Aft she was fitted with a full cabin which had an overhang out to the sides of the ship extending for the entire length of the deckhouse. The funnel was of medium height but was quite thick for a canaller and was surmounted by a very prominent cowl. When SAND MERCHANT entered service, she carried the distinctive Mapes and Fredon funnel design, a black stack with three gold bands. Her hull was painted black and her cabins white.

The year 1931 saw the Royal Trust Company, Montreal, take possession of SAND MERCHANT, presumably because of unpaid accounts (which might have related to her original construction). Royal Trust then chartered the boat to the National Sand and Material Company Ltd., Toronto, a subsidiary of Standard Paving and Materials Ltd., Toronto. The Great Depression was, however, inflicting its miseries upon the business community at that time and SAND MERCHANT operated only intermittently in 1932, spending the rest of her time at the wall in Toronto harbour. In 1933, there was no work at all for either SAND MERCHANT or CHARLES DICK and National Sand kept both steamers laid up for the season in Muir's Pond above Old Lock One in the third Welland Canal at Port Dalhousie.

Business improved somewhat after 1933 and in 1934 SAND MERCHANT operated intermittently again. The three subsequent years, 1935, 1936 and 1937, saw the ship in full operation, normally on Lake Erie where she would load sand off the Canadian shore and deliver it to Cleveland in much the same manner as did CHARLES DICK in the latter years of her career.

The autumn of 1936 saw SAND MERCHANT in operation, as usual, on Lake Erie. On Saturday, October 17th, the steamer completed her task of loading sand off Point Pelee and at about 1:15 p.m. she got underway for Cleveland which lay 36 nautical miles away, southeast by east. The weather was fine and clear, but there was a strong northwest wind blowing which at times reached a velocity of 30 to 38 m.p.h. The weather deteriorated as the trip progressed.

SAND MERCHANT had covered seven miles of her voyage when the steering transmission cable on the starboard side leading from the pilothouse aft to the steering engine gave way. The ship, which was under the command of Capt. Graham MacLelland, was stopped and the steering cable was renewed. To get at the broken cable, it was necessary to remove the covers of the starboard buoyancy tanks but these covers were apparently replaced securely before the ship resumed her voyage to Cleveland at about 6:00 p.m.

Later in the evening, about 8:30 p.m., the second officer, Wilfred John Bourrie of Victoria Harbour, Ontario, called the master because the ship had taken a port list of about five degrees. The master had been asleep on the settee in the wheelhouse as he had been on duty throughout the preceding night and during the morning to supervise the loading and, in addition, he had been on the bridge throughout the repair of the steering cable. The master, having been called by the second mate, immediately went aft to inspect the cargo hoppers and he found that the after hoppers had shipped a considerable quantity of water. Capt MacLelland then proceeded to have the ship's head brought into the wind to try to correct the list, but by 9:00 p.m. he found that this manoeuvre had not produced the desired effect. The list had developed further and was gradually increasing. The sea had also risen somewhat and water was being shipped over the sides into the open cargo holds. With her load of about 3,000 tons of sand, she would have had a freeboard of about 3 1/2 feet had she been on an even keel at this point. It should be noted that SAND MERCHANT was equipped with four large buoyancy tanks fitted on each side of the cargo holds fore and aft, extending from the side of the ship toward amidships.

Finding that he could not keep SAND MERCHANT'S head up to the wind because she was becoming loggy, the master let go the starboard anchor and ordered that distress signals and flares be sent up and that the officers should get out the boats. He enquired as to the state of the buoyancy tanks and was informed that they were dry. Capt MacLelland remained on the bridge, working his engines, and sent the wheelsman aft to assist in the launching of the lifeboats. It was impossible at this stage to take soundings of the tanks because of the water coming onto the decks. The cargo elevator buckets were operated but revealed no water in the tunnel or conveyor space. Operation of the pumps in the engineroom showed that there was no water in the portside buoyancy tanks.

Difficulty was experienced in lowering the boats. The starboard boat could not be lowered due to the list and was finally cut loose and allowed to remain on deck so that it would float off in the event that the ship foundered. The port lifeboat did reach the water and was afloat for some minutes before SAND MERCHANT gave two final lurches to port, turned over on her side, and immediately sank. The actual sinking occurred at about 10:00 p.m. when the steamer was some 17 miles northwest of Cleveland.

A few crew members had been able to board the port lifeboat before the sinking but the boat capsized when SAND MERCHANT went down. Capt MacLelland was able to jump from the bridge just as his vessel rolled over on her side. The unlaunched starboard lifeboat also capsized during the sinking. All the Crewmen were thus thrown into the water and those who were able regained the overturned boats. The survivors maintained their precarious hold on the boats until the morning of Sunday, October 18th. Capt MacLelland reported later that as the lanterns and flares were stored inside the overturned lifeboats, the men in the chilling water had found no way of showing a light despite the fact that several ships had passed close to the lifeboats during the night, some of them coming as close as one-half mile.

With the coming of daylight, the three survivors clinging to one boat were rescued by the steamer THUNDER BAY QUARRIES in command of Capt. James Healy. There were four survivors clinging to the other lifeboat and they were picked up by the collier MARQUETTE and BESSEMER NO. 1. In all, 19 of the 26-man crew were drowned, including the first mate, Bernard Drinkwalter of Port Stanley and his wife, second mate Bourrie, and chief engineer Walter MacInnis.

The preliminary investigation into the foundering was conducted by Capt. Henry W. King of Toronto, government examiner of masters and mates. As a result of his findings, a formal and thorough investigation was held at Toronto by Mr. Justice E. M. McDougall of the Quebec Superior Court acting as wreck commissioner. Capts G. D. Frewer and L. McMillan served the inquiry as nautical assessors.

After lengthy hearings, the court found that Capt. MacLelland had done all within his power to save the ship and was in no way responsible for the foundering. The court advanced the opinion that the responsibility for the loss of life must be laid upon the shoulders of the first officer and, to a lesser degree, upon those of the second officer, first of all for failing to call the master sooner when it should have been evident that something serious was amiss and in addition for failing to get the crew off and the boats away. Both these officers, Drinkwalter and Bourrie, were drowned.

The court also found that the foundering of the ship was not caused by any wrongful act or default of the operating company. SAND MERCHANT was well-found and had been maintained in good condition with ample buoyancy reserve and full stability. She had been inspected by Canadian government inspection officials and had been declared to be seaworthy in every respect. The court found that at no time had the master been urged to overload or otherwise reduce the efficiency or stability of the ship.

The court did decide that some criticism was to be levelled against the master for the reason that there had never been a boat drill aboard SAND MERCHANT. The wreck commissioner stated that "here was, no doubt, laxity of discipline, but the loss of life can scarcely be ascribed to this cause as the direct consequence of such neglect". Capt MacLelland was not censured for his indiscretion in not holding boat drills. It was found, however, that the presence aboard ship of the wife of the first officer distracted his attention from his duties and the master was censured for having allowed Drinkwalter to bring his wife on board for the trip.

It was suggested by a technical witness who was called to testify at the hearings that water must have penetrated to the port tanks but neither this expert nor any of the other witnesses could say for certain how the water might have got into the buoyancy tanks. The court found that "if, for one reason or another, the special hatch cover giving access to the Number One buoyancy tank had not been replaced (after the repair of the steering cable), the considerable aperture so created at this then vulnerable point in the vessel's protection would have admitted quite sufficient water to the port tank to increase and aggravate the existing list to a point where all further stability in the vessel would disappear and her foundering become inevitable."

In conclusion, the court recommended "that a Board of Inquiry be set up, consisting of men skilled in nautical matters, to conduct an investigation into the design, construction and navigation of ships of the type of the SAND MERCHANT, with particular regard to such subjects as possible application of load line regulations to lake vessels; construction and possible change in the design of open hoppers on vessels of this type; necessity of regulations concerning boat drills; attention to superstructural loading and unloading equipment and facilities; storage of cargo bearing on stability of the vessel and methods of discharge of water from cargo space; and the possible provision of protected emergency access to buoyancy tanks from machinery space aft or pump space forward." We can find no record of the results of such inquiry if, indeed, any such inquiry was ever held.

And so, although a good many theories have been put forward over the years, the actual cause of the sinking of SAND MERCHANT has never been determined. Our own thought would have to be that regardless of the fact that other factors of unknown nature may have been operating, the officers of SAND MERCHANT should probably never have commenced the crossing to Cleveland in the weather conditions that were then prevailing, knowing that the ship could have remained in relatively calm water by staying where she was in the lee of the Canadian shore.

As the years have passed, there have been thoughts given to the raising of SAND MERCHANT, but forty years have now gone by and still she remains on the bottom of Lake Erie, holding deep within her any evidence there may be to explain her mysterious capsizing and the snuffing out of the lives of nineteen persons.

Previous Next

Return to Home Port or Toronto Marine Historical Society's Scanner

Reproduced for the Web with the permission of the Toronto Marine Historical Society.